Label Detective: Are we alone in here?

By tcrnkl0, on 20 September 2017

In the first two instalments of the Label Detective series we investigated the meaning of the word cynocephalus and the impact of British eugenics on Egyptian archaeology. Now we’re moving over to the Grant Museum of Zoology to tackle the label mysteries of the animal kingdom.

Case 4

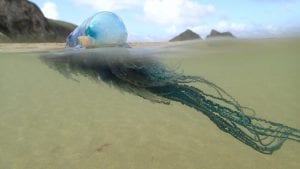

Let’s start with the Portuguese Man O’War. Here’s a picture of one floating peacefully (and extremely poisonously) in Cornwall earlier this month.

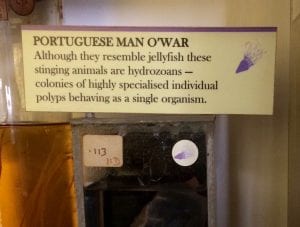

And here’s the label on the specimen in the Grant Museum.

This is my bad photo. There’s a better picture of the specimen underneath at the bottom of this post.

The Label: I got curious about the Portuguese Man O’War because the label uses the word ‘colony’ here in a way that I didn’t really understand. When we talk about colonies in the animal kingdom we are usually referring to insects, like bees or ants, where lots of individuals make up a colony. But what does it mean for a colony to make an individual? In the case of the Portuguese Man O’War, a siphonophore, four different types of polyps come together to make an individual like the one pictured. Each kind of polyp has a different function. The inflated bladder, or sail of the Man O’War, helps the creature to float. Then there are reproductive polyps, eating/digestive polyps, and ones that provide the Man O’War’s stinging defence. These latter three types of polyps are themselves made up of groups of individuals called zooids. It’s multiplicities all the way down.

Case Notes: The polyps and zooids that make up a Portuguese Man O’War are genetically identical, and so specialised as to be interdependent (though the individual zooids are structurally similar to other independent species) – so in many ways it does make sense to consider them an individual. But it challenges assumptions that an individual is something entirely singular or uniform.

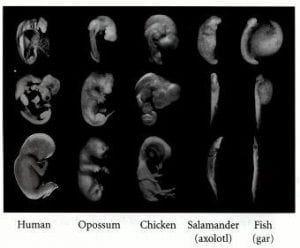

‘Individuals’ are rarely a closed, or self-contained system. What does this mean? Consider you and your mother. When you are a fetus, some of your cells pass through the placenta and take up residence in your mother’s body. You also get some of your mother’s cells. Even weirder, if you aren’t your mother’s first child, you not only get your mother’s cells, but cells from all your siblings as well. You don’t just have other people’s cells in your body — you also have loads of cells that aren’t human at all. Developmental genetics and embryology scholar Scott F. Gilbert says: ‘Only about half of the cells in our bodies contain a “human genome.” The other cells include about 160 different bacterial genomes. We have about 160 major species of bacteria in our bodies, and they all form complex ecosystems. Human bodies are and contain a plurality of ecosystems.’

These examples are not the only way that genetic transfer is more diverse than the Darwinian model of sexual selection (i.e. getting all of your genes from two parents). And a lot of these more varied and spectacular ways are down to bacteria. Next time on Label Detective, we’ll get into these messier models of evolution.

Status: I would say case closed, but since I’ve just spent the blog post arguing against the concept of a closed system, this seems wrong. But we’re done for now.

Notes

This post was inspired by the book Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, an anthology of essays by zoologists, anthropologists, and scholars that explores how environmental crisis highlights the complex and surprising ways in which all life on earth is entangled. The quote from Scott F. Gilbert comes from his contribution to this book.

Close

Close