Contemplating the Cat

By Arendse I Lund, on 28 September 2016

by Arendse Lund

Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the Internet, was once asked what surprised him most about his creation. His answer? “Kittens.” The feline statistics are both impressive and shocking: according to Friskies up to 15% of Internet traffic is cat related; cats get almost 4x the viral views as dogs on Buzzfeed. You don’t even need to seek out cat-related content during your daily Internet perusals; unless you have certain plug-ins, inevitably the cats come to you.

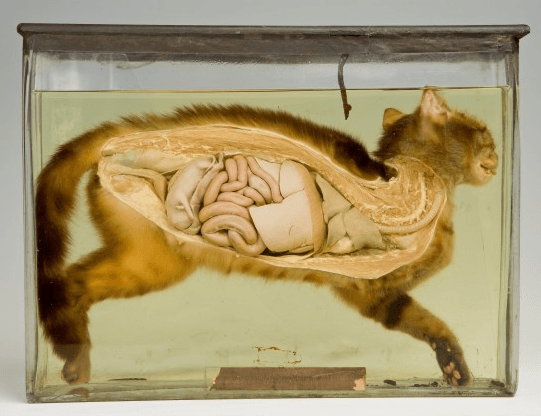

While cats seem to be the lingua franca of the web, the proliferation of cat gifs, memes, and photos is only magnifying a greater trend, one which continues offline as well. Children and adults alike ooh and aah over the Grant Museum’s display of bisected cats. Keen-eyed visitors may even spy with delight the embryonic kitten nestled in the womb of one of the specimens. There’s accessibility in the cats’ familiarity; this appeal extends to all ages if the toddler-height fingerprint smudges on the display cases are anything to go by.

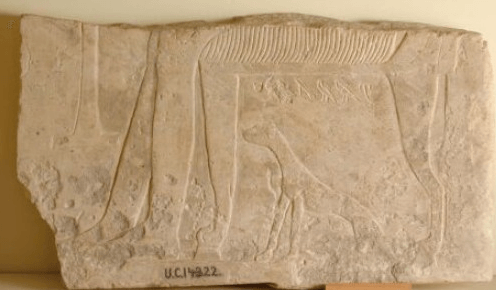

Cats have fascinated diverse cultures for millennia. Linking cat lovers today with those three thousand years ago, the Petrie Museum has an entire display case dedicated to Ancient Egyptian cat statuettes and artefacts. Throughout the Egyptian dynasties, the felines were associated with several goddesses and revered in their own right for their ability to kill vermin—including cobras. Cats were also known to be mummified and buried after death.

Much later, a similar fascination with cats can be found in an entirely different part of the world—medieval Europe. Illuminated manuscripts were the Internet of the times and cat references can be found scattered across those vellum pages. One early Irish monk wrote a poem in praise of his cat, Pangur Bán. From Robin Flower’s translation:

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

‘Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night…

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

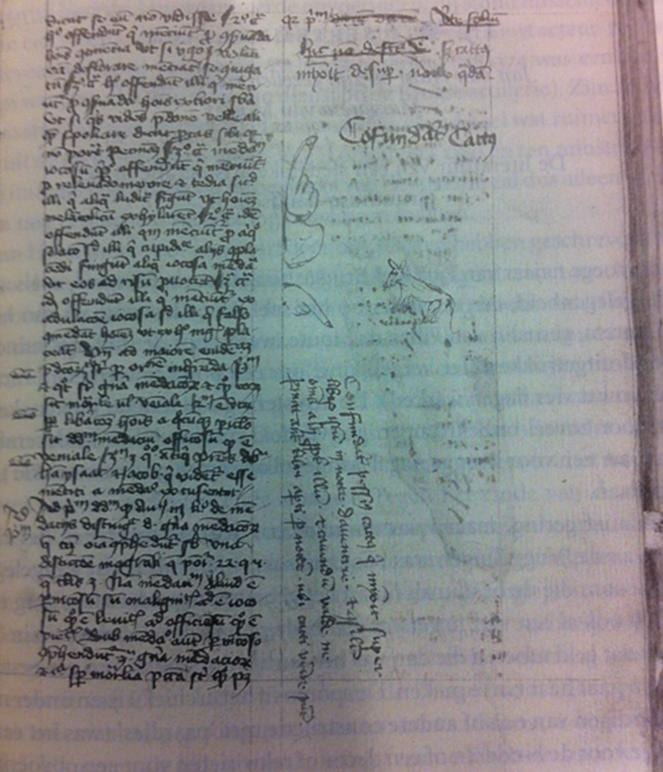

Green pigment has eaten through the parchment in the shape of a cat. (National Library of Wales, Peniarth MS 28, f. 26r)

In Vatnsdœla saga, Thorolf Sledgehammer is the proud owner of twenty cats who defend him from attack. One might wonder if the writer had much knowledge of cats—rottweilers they are not. However fanciful that story was, cats served a useful function as pest control. A mid 13th-century Welsh manuscript containing the laws of Hywel Dda directs that payment be made if a cat is killed. Four pence should be paid to the owner if the cat is old enough to hunt mice; a kitten too young to open its eyes is only worth a single penny and one able to see but too young to hunt worth two pence.

The common sight of cats slinking around monasteries may have made them familiar source material for illuminators working on the manuscripts. Perhaps the medieval version of a Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinks cartoon segment, one illuminator drew a historiated initial depicting a dog catching a cat catching mice. Cats are a common sight in manuscripts where they find themselves in an abundance of absurd situations.

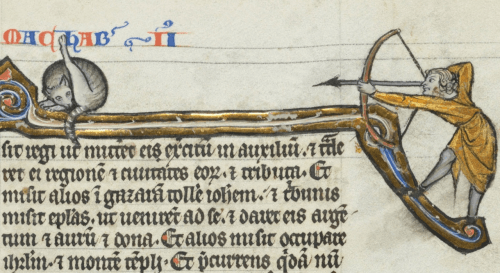

In the 13th-century Book of Maccabees, an archer takes aim at a cat who is busy ensuring it’s clean absolutely everywhere. Cat owners are accustomed to this sight and, clearly, so was the illuminator. There are plenty more strikingly similar images of this theme found in medieval manuscripts.

In another instance of cat behavior which hasn’t changed all that much, the 14th-century illuminator of the Maastricht Hours depicted a cat playing with a nun’s spindle. Cats were such a common sight and part of daily life that the Middle English Ancrene Wisse permitted anchoresses to own a cat but no other animal. In the 15th century, Exeter Cathedral had a resident mouser on the payroll who earned one penny per week; someone even cut a cat flap in the cathedral’s south tower door which can still be seen today.

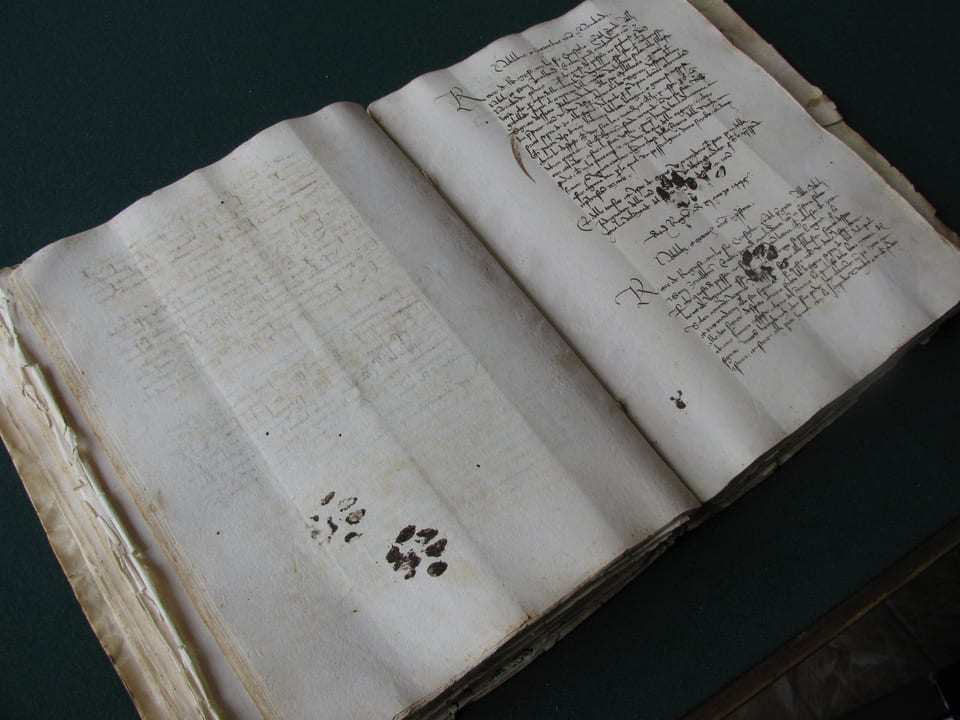

Dubrovnik State Archives, Lettere di Levante. (Photograph by Emir O. Filipović)

Not all cats are depicted positively though and some aren’t intended to be depicted at all. One fine furry fellow left its mark all over the Lettere di Levante from the Dubrovnik State Archives. Pet owners may sympathize—the pages of the manuscript accidentally recorded where an inky-pawed cat walked across it.

However useful cats could be to have around, they could be disruptive as well. The blank half of the delineated page above, along with the manicules and cat sketch, was not initially planned in the 15th-century manuscript. What appears to have happened is that the scribe working on this left the manuscript out over night and came back to an unpleasant surprise. The scribe wrote an exasperated note in the margins: “Nothing is missing here, but one night a cat urinated on this. Cursed be the mischievous cat that urinated over this book during the night in Deventer and similarly all the others too. And pay heed to not leave books open at night where cats can reach.” We would all do well to heed that advice.

As our ancestors were fascinated with cats, so are we. There’s something entrancing about the felines and that something has spoken to humans across cultures and time periods. While our medieval forebearers might have had to make do with sharing manuscripts rather than cat gifs, nowadays we can be endlessly entertained by the felines with a click of a mouse.

2 Responses to “Contemplating the Cat”

- 1

-

2

Medieval Snowball Fights | UCL Researchers in Museums wrote on 21 December 2016:

[…] Contemplating the Cat […]

Close

Close

This piece is for my fellow cat lovers out there. Because cats are the best. #TrueFacts #NoExaggeration… https://t.co/EHHZWtb223