Portrait of a Man and His Dog: The Brown Dog Affair

By Gemma Angel, on 22 October 2012

by Alicia Thornton

by Alicia Thornton

The prospect of finding a link between my own work (infectious disease epidemiology) and the collections in the UCL Art Museum seemed somewhat daunting at first. However, looking through the collections catalogue, I recently came across a portrait which instantly intrigued me.

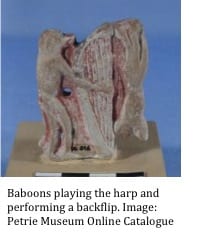

The artist is Walter Westley Russell, a painter born in Essex in 1867.[1] The reason I was drawn to this portrait is the setting in which the man is pictured. He appears to be in a laboratory and is depicted standing next to a dog which seems to be either undergoing some kind of surgery, or is the subject of an experiment. As a scientist, I was interested in finding out what this experiment or surgery had been about and why the subject, Professor EH Starling, had been pictured in this way.

Starling became Professor of Physiology at UCL in 1899, where he became well known as an enthusiastic experimenter. One of his most important discoveries was the role of a hormone in pancreatic secretion. Pavlov had previously conducted experiments, for which he later won a Nobel Prize, showing that when gastric acid was present in the large intestine pancreatic juices were secreted. He believed that this was entirely under the control of the nervous system: when gastric acids were present in the intestine, the nerves sent a message from the walls of the intestine to the pancreas, via the brain, and the juices were released.

Starling, along with his brother-in-law William Bayliss, conducted an experiment where they stripped away the nervous tissue surrounding the large intestine. They found that when the nerves were removed the pancreatic secretions still occurred. This raised the possibility that the secretions were controlled by another system (what we now know to be the endocrine system). Starling and Bayliss hypothesised that the presence of gastric acids in the intestine caused the release of some kind of soluble substance into the blood which in turn cause the pancreatic secretions to occur. To test this theory their next experiment was to remove a small portion of the lining of the intestine of a dog. They crushed the tissue, added acid to it (mimicking the presence of gastric acid in the intestine), and injected it into the blood of an anesthetized dog. Pancreatic secretion duly followed. So clearly the nervous system was not responsible for triggering these secretions and in fact the intestinal tissue did not even need to be in situ for the secretions to occur. This indicated to Starling and Bayliss that some substance was produced by the intestinal tissue, in response to the acid, and was carried in the blood to the pancreas where release of pancreatic juices was then stimulated. They named this substance, produced by the intestine and carried in the blood stream, secretin.[2] This was only the second ever description of any kind of endocrine substance.

Starling has, in fact, been credited with the introduction of the word hormone into the English language. After a dinner at a Cambridge college he and his colleague, the biologist William Hardy, were discussing their recent work and agreed that there was a need for an appropriate word for those agents which are released into the blood and cause activity elsewhere in the body. They consulted classicist WT Vesey who provided them for the Greek word for “I excite” or “I arouse”: ormao. Thus they settled on the word hormone which Starling first used in a lecture at the Royal College of Physicians in 1905.[3]

E.H. Starling, by Walter Westley Russell (1926). UCL Art Museum Collections; Image supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

It appears therefore, that the dog in this painting is a reference to Starling and Bayliss’ important experiment and their discovery of secretin. However, it is possible that the importance of Starling and Bayliss’ discovery is not the sole reason that the professor is pictured with a dog in his portrait. Bayliss and Starling conducted many of their experiments as demonstrations to students. Unbeknownst to them their classes had been infiltrated by two women from Sweden who were anti-vivisection activists. The women believed that the dog had not been appropriately anesthetised and showed also that the dog had been used for more than one experiment contravening the 1876 Cruelty To Animals Act. The testimonies of the women lead to a heated political argument. Bayliss and Starling were never tried under the Act. However, the arguments did not end with politicians, and anti-vivisection campaigners decided to erect a memorial to the dog in Battersea Park with a plaque which read:

In memory of the brown terrier dog done to death in the laboratories of University College in February, 1903, after having endured vivisection extending over more than two months and having been handed from one vivisector to another till death came to his release. Also in memory of the 232 dogs vivisected at the same place during the year 1902. Men and women of England, how long shall these things be?

Medical students in London were angered by the plaque, believing that vivisection was vital to their studies and the advancement of medical science. They repeatedly attacked the memorial and protested against it. The climax of what is now known as “The Brown Dog Affair” occurred in December 1907 where riots broke out both in Battersea and central London and the medical students clashed with police and anti-vivisection campaigners. Eventually the council took the decision that the cost of policing the memorial to the Brown Dog was too great and the statue was quietly removed in 1909.[4]

Starling is pictured in his portrait conducting an experiment on a small brown dog. Whether this is the same brown dog which caused the riots cannot be known but certainly conducting these experiments was central to Starling’s contribution to medical science, whilst also angering many who believed that what he had done was wrong. Discussions about using animals in scientific experiments continue today and though there are now a range of alternatives, animals are still used in certain circumstances. My own research uses data from human subjects. Like all clinical research, it must be approved by an independent ethics committee before being conducted. While the process of having a research study approved may sometimes seem painful and tedious, stories like this one remind us of the importance of having research proposals reviewed by those who may have different attitudes to those of the scientists involved in experimental research.

References

[1] Oxford dictionary of National biography: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35887

[2] Bayliss, W.M. & Starling, E.H. (1902) The mechanism of pancreatic secretion. Journal of Physiology 28: 325-353.

[3] Henderson, J. (2005) Ernest Starling and Hormones: An Historical Commentary. Journal of Endocrinology 184: 5-10.

[4] Mason, P. (1997) The Brown Dog Affair. Two Sevens Publishing.

Close

Close