The Unsung Heroes of UCL Museums and Collections

By ucwehlc, on 6 July 2021

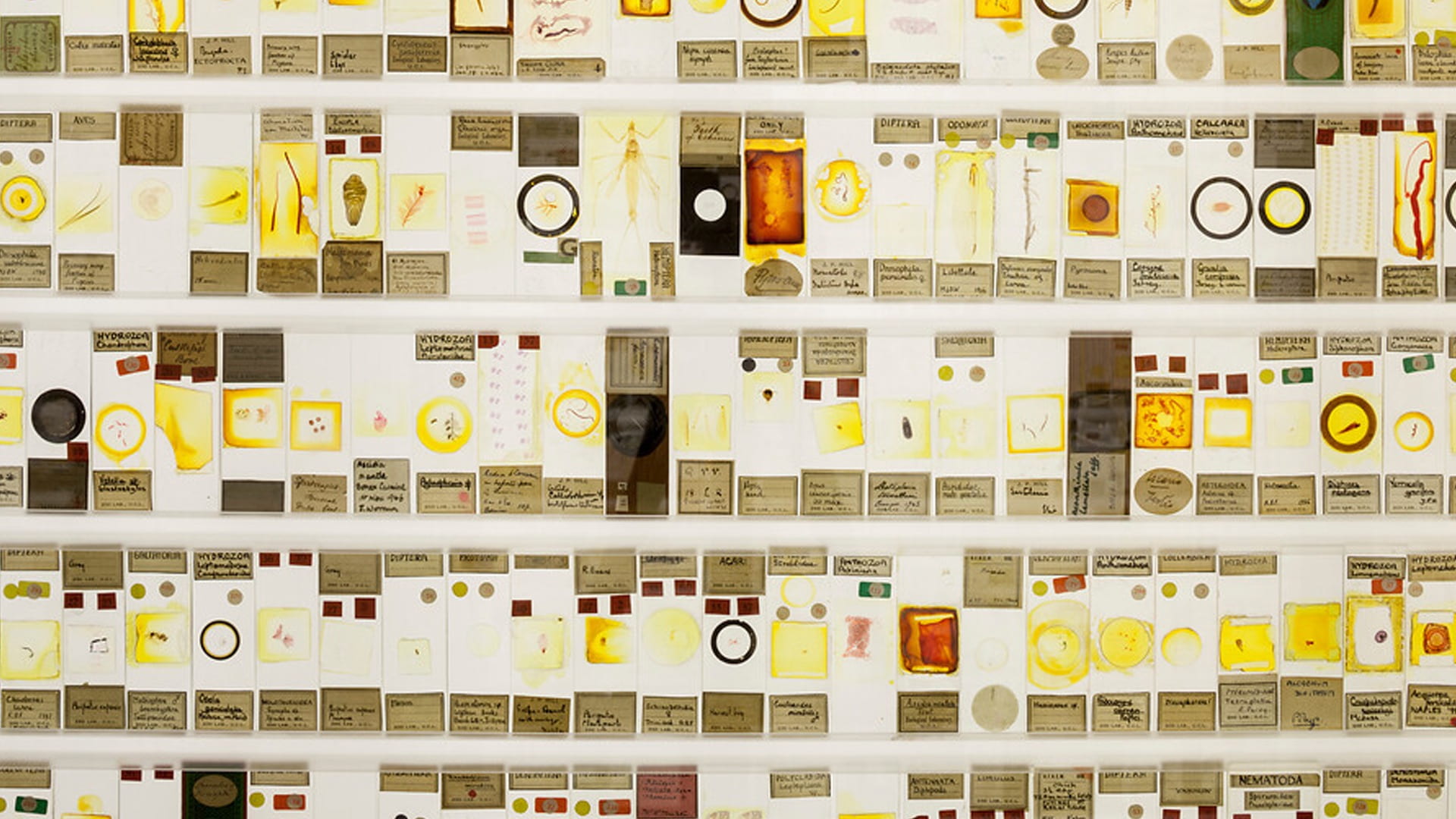

During 2020 and 2021 while UCL was closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, UCL Culture’s curatorial team worked with students from the Institute of Archaeology’s MA Museum Studies on our first-ever virtual work placements. These projects, which included archive transcription, documentation and object label writing, provided opportunities for the students to gain practical curatorial skills to prepare them for their future careers while undertaking valuable work towards better understanding the collections.

This blog was written by Nicky Stitchman, UCL MA Museum Studies

As part of my MA in Museum Studies, I undertook a work placement with Hannah Cornish, Science Curator at UCL. My brief was to discover the different locations of UCL’s museums and teaching collections from the university’s origins in 1828. Ferreting out information from primary and secondary sources and finding maps that showed the movement of the various museums as the university expanded was fascinating, but I found myself drawn to people behind the museums. I am not talking here about the headliners – the Flinders Petries or Robert Grants of this world – but rather the curators, assistant curators and demonstrators who would have done most of the day-to-day tasks such as cataloguing, labelling, teaching, and physically moving the artefacts and objects within the collections.

James Cossar Ewart at the Grant Museum

J Cossar Ewart was the first professional, rather than professorial, curator of both the Anatomical Museum and Comparative Anatomy/Zoology Museum between 1875-1878. He was appointed after the retirement of William Sharpey (curator of the Anatomical Museum) and the death of Robert Grant (professor of comparative anatomy). In the official records, it was Professor Lankester, Grant’s successor, who refitted and rearranged the Museum of Zoology over this period but Ewart was instrumental in making the zoological preparations and was also known to have helped organise and take the subsequent practical classes that Lankester introduced to UCL.

After Ewart, there was a change in the running of the two largest museums at UCL at that time, with a separate curator appointed for the Museum of Anatomy, while the Zoological Museum (now the Grant Museum of Zoology) was titularly run by the Head of Department with a curatorial assistant.

Shattock and Stonham: Anatomy and Pathology

Mr Samuel Shattock succeeded Ewart as the Curator of the Anatomical and Pathological Museum. He had originally shown up in the records as a Mr Betty which caused me some confusion at the time, until I discovered that he had decided to change his name to prevent the extinction of the Shattock family name! Shattock never qualified as a physician but dedicated his life to pathological medicine. He was responsible, alongside Dr Marcus Beck, for a descriptive catalogue of the surgical pathology preparations at UCL. His successor Charles Stonham also worked with Marcus Beck on Part II of this catalogue and then in 1890 produced another medical pathology catalogue, which can be found online at the Wellcome Collection. In the preface to this catalogue, Dr Barlow and Dr Money acknowledge the work of Charles Stonham, and state that it is ‘to him the preparation of this work is almost entirely due’.

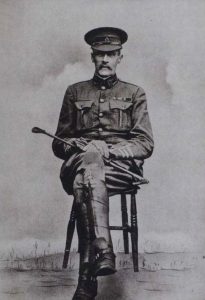

Stonham was also responsible for the division of the pathology from the anatomy collection and its rehousing within the museum. He is also remembered on the UCL Roll of Honour as not only was he an instrumental figure in the London Mounted Brigade Field Ambulance, but he volunteered as a member of the Royal Army Medical Corps during WWI and died on service in January 1916 aged 58.

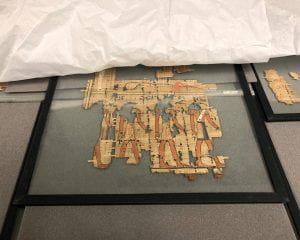

Margaret Murray and the Petrie Museum

The dedication of many assistant curators at UCL is very clear. The redoubtable Margaret Murray (pictured here), who worked alongside Flinders Petrie for many years, was effectively in charge of the museum’s collections during Petrie’s many excavations in Egypt and the Levant. It should also be remembered that the Petrie Museum of Egyptology and the Department itself was founded on the collection and endowment of Mrs Amelia Edwards, who favoured UCL due to the early admission of women into the College.

Edith Goodyear and the Geology Museum

One of the first women to be involved in UCL’s museums was Edith Goodyear who was appointed as the Assistant in the Geology Museum in 1904 and subsequently remained in the department until the Second World War. Edith worked alongside Professor Edmund Garwood, reorganising the museum, teaching, and researching papers. A room in the Lewis Building was named for her, along with the First Year Student prize within Earth Sciences. It is also worth noting that in an age of inequality, the 1916/17 council minutes show Edith was paid £150, the same as her male colleague Dr J Elsden.

Keeping it in the family: Mary and Geoffrey Hett

1917 also saw the appointment of Mary L Hett as Assistant in the Zoology Dept on the same salary of £150, where she remained until she took up the post as Professor of Biology at the Hardinge Medical College, Delhi. She had followed her brother Geoffrey S Hett to UCL where he held the post of Curator of the Anatomical Museum from 1907-1910. Like his sister, he had a great interest in the natural world and was an authority on both British birds and on bats. Geoffrey became an ENT Specialist and during his time at UCL completed valuable research on the anatomy of the tonsils. Like his predecessor, Charles Stonham, he also served in World War I and used the skills learnt at UCL to treat head, and in particular, nasal injuries during this period.

The stories of the men and women who studied and worked at UCL museums over the years are many and various, and these are just a sample of those whom I have met in my research for the Mapping UCL Museums Project. We may never be able to give the Curators and Assistant Curators the recognition that their work and dedication deserve but in introducing these few to you, I hope to have redressed the balance very slightly in their favour!

Close

Close

“Anyone who has spoken to me knows – the Socks! 🙂 Again as an archaeologist I get way more excited about the preservation of materials that we don’t normally see far more than gold and treasure (which survive well). So first, I simply love that wool has survived. Secondly, I had absolutely no idea that Ancient Egyptians knitted or wore woollen socks; it was really surprising, although in retrospect desert temperatures do drop very low at night.” – Sian

“Anyone who has spoken to me knows – the Socks! 🙂 Again as an archaeologist I get way more excited about the preservation of materials that we don’t normally see far more than gold and treasure (which survive well). So first, I simply love that wool has survived. Secondly, I had absolutely no idea that Ancient Egyptians knitted or wore woollen socks; it was really surprising, although in retrospect desert temperatures do drop very low at night.” – Sian