The Return of the Rhino: Conserving our biggest skeleton

By Jack Ashby, on 10 February 2015

In November, we announced that Reg the (hornless) Indian one-horned rhino skeleton was being dismantled and taken away for an extreme make-over (read Dismantling Reg the Rhino in Ten Easy Steps). Now he has returned in much better shape (specifically, rhino-shaped), prepared for a long and prosperous future in the Museum.

Reg, a Bone Idol

The rhino was among the first specimens included in our huge conservation project Bone Idols: Protecting our Iconic Skeletons, which will secure the long-term future of 39 of our biggest, rarest and most significant specimens. Some will be cleaned of 180 years of particulate pollutants, some will be repaired, some have new cases built, and some, like the rhino, will be completely remounted.

What was wrong with the rhino?

The Bone Idols project seeks to significantly prolong the “shelf-lives” of our specimens so we can continue to use them, as we do today, in teaching, research and public engagement.

The rhino skeleton came to the Museum as loose bones in 1911 from the “University South Kensington collection” also referred to as the University of London Loan Collection, and was mounted on an iron frame, along with three other big skeletons, for the bargain price of £14. It would be easy to say “you get what you pay for”, but that might be unfair as the ironmongery skills used were impressive, and that rarely overlaps with training in skeletal anatomy.

The primary goals of Reg’s makeover were to clean the skeleton of the nasty grime that coated him, built up after 104 years on open display, much of which was spent in a room lit by oil lamps; and to stabilise his mount to be less precarious. At the same time we would reposition him so he was actually rhino-shaped.

The first thing I said when the doors to the van opened and I saw Reg was “it’s a completely different colour!” Before, Reg was off-white, as you might expect bone to be. This was actually dust and dirt. Now Reg is the woody brown colour of old bone.

Rhino remodelling

The spine

Rhinos spines curve downwards from the hips to the shoulders, and then down again along the neck. The “old” rhino’s spine was ruler-straight and parallel with the floor, before a neck that pointed up.

The shoulders are now lower than the hips, and the head lower still, but we found that we couldn’t introduce a natural curve along the spine. The bones of the spine and pelvis were actually more solidly attached than we realised. We thought that they were simply held in place by a single iron rod running through the neural arch of the vertebrae (the space for the spinal chord). In fact, not only was that rod fixed by a strong resin, but a thinner rod had been drilled and glued through the main body (centrum) of each vertebra and through the pelvis, making it immovable.

The rhino being reassembled – the new position has the hips higher than the shoulders, with the neck angled down.

We faced the decision of whether to cut the pelivis free and force the two rods out of each vertebra. The alternative was to keep an unnaturally straight spine. In the end the risk to the specimen was too high, and we left the rods in place.

Although its back is still straight, the hips have been raised and the shoulders dropped, so an overall accurate shape has been achieved without damaging the bones. The neck now points downwards, as it should, and an extra upright support is holding its heavy skull in space, adding a great deal of stability.

The legs

The “old” rhino’s legs did not fit into its pelvis – they floated freely in the air, disassociated from the body. Not only that, but the head of one femur was not on the skeleton. Normally, the tips of bones (the “growth plates” or epiphyses) fuse to the bone shafts during an animal’s adolescence. The rhino is definitely adult, so we were surprised that the femurs had not fused. Apparently this does happen with large mammals like rhinos and elephants.

The epiphysis has been reattached, and the legs’ supports shortened and reshaped to allow them to sit in properly the sockets.

The legs all now touch the ground, which they didn’t before. Not only does this add a lot of stability, it doesn’t imply that rhinos could fly.

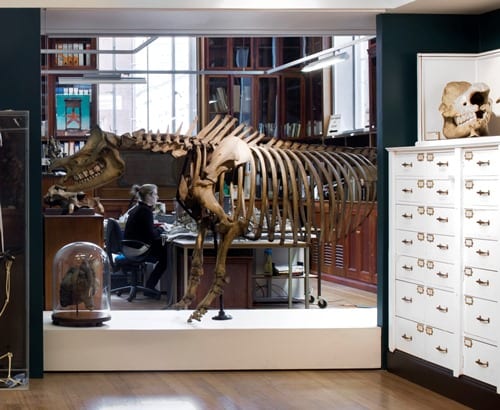

A view of the “new” rhino from within the Museum office (we believe that ours is the only office in the world with a rhino for a wall), showing that the legs all fit, and the spine is correctly positioned

A skull of wood, leaves and flies: things we learnt

The rhino had some surprises for us, and not just the way the metal was integrated with the skeleton:

- When the grime was cleaned off, it turned out that one of of its lower incisor “tusks” was made of wood, as were both upper incisors.

- The conservator, Nigel Larkin, found evidence of the rhino’s last meal among its teeth – some grassy leaves.

- Inside its nose was a mass of insect larvae casings. This isn’t unusual in museum specimens – household insect pests like clothes moths and carpet beetles regularly eat soft tissue on museum specimens. However, a Twitter investigation identfied them as rhino bot fly – a rare parasite of live rhinos.

These bad boys fell out of our (hornless) rhino’s nose postmortem but premuseum? Any insectologists help with an ID? pic.twitter.com/dglkerR0vL

— Grant Museum, UCL (@GrantMuseum) February 2, 2015

Do come and visit the spruced-up Reg, and please do support the Bone Idols campaign by donating online – we have a lot more work to do.

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

2 Responses to “The Return of the Rhino: Conserving our biggest skeleton”

- 1

-

2

The world’s rarest skeleton returns to the Grant Museum | UCL UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 1 May 2015:

[…] questionable mounting. The second was taken on Tuesday, when she returned to us. The quagga (and our rhino) were the biggest single tasks for our massive conservation project Bone Idols: Protecting our […]

Close

Close

[…] Reg the Rhino -the largest skeleton in the Museum – was treated in this group and has now been remounted in fine form back on his plinth. […]