Social Exclusion in the Ger Districts of Ulaanbaatar

By uczipm0, on 24 June 2015

This post was written by Terbish Bayartsetseg, a lecturer of Social Work at the School of Arts and Sciences at the National University of Mongolia. Bayartsetseg has been involved in a range of projects relating to community development practices. She is an affiliate researcher on the Emerging Subjects project and is a paired researcher to Rebekah Plueckhahn.

Urbanization and expansion of ger districts in Ulaanbaatar

Sedentary culture as we now know it in Mongolia began quite recently. Scholars who have studied urbanization in Mongolia agree that this began in the second half of the 20th century.[1] Other scholars refer to the 1700s or the times of the Ikh Khuree when discussing people shifting from nomadism to settlement living in Mongolia.[2] By 1960, it was reported that construction developments in Ulaanbaatar city attracted rural populations like “a magnet”[3] because of Ulaanbaatar’s employment, business, and commercial opportunities. Urbanization processes were exacerbated by the 1990 democratic movement and transition from socialism to a market economy in Mongolia. Furthermore, the first democratic Constitution of Mongolia of 1992 entitled its citizens to freely move, settle in and change the residential destination within its territory. By 2015, the population of Ulaanbaatar rose to 1.37 million, where approximately 64.2% of Mongolia’s total population[4] now resides in the capital.[5] More disaggregated data by tenancy shows that, by 2014, nearly 60% of the urban population reside in ger districts due to the increasing costs of apartment options.[6] Today, ger districts exist in all nine districts of Ulaanbaatar with particular growth over the hills and hollow valleys in Sukhbaatar, Chingeltei, Songinokhairkhan and Bayanzurkh districts.

As one of the oldest types of residence in the world, a ger is a traditional dwelling used by Mongolian people from early times until today. It is constructed with a combination of poles and felt, which can be easily collapsed and built up again within an hour or two. Until 1920, gers have been primary sources of housing for nomads and are used today as an alternative to wooden houses.[7] Mongolians live in gers all through the year, by adding the number of felt covers surrounding it during the coldest months. Residents of the ger districts have mostly relocated to the city seeking employment opportunities and hoping for access to better education for themselves and their children. Due to the growing urban population, the current local educational institutions as well as health clinics are outnumbered, and resources are stretched, presenting problems for the government.

Ger District Sections and Current Planning Initiatives

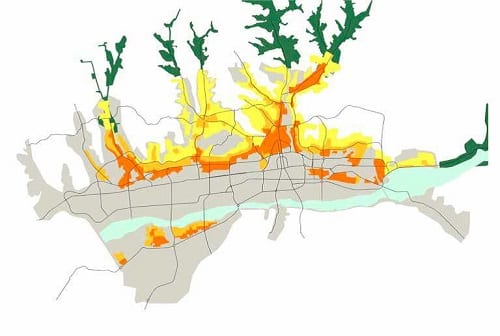

The ger districts are divided into three sections: central, middle and peripheral.[8] As indicated in Figure 1, middle and peripheral areas of settlement covers vast areas in Ulaanbaatar. These districts are located in territories where connections to heating and waste disposal engineering schemes are not available. Thus, the Government has strategically planned to implement more cottage structures in the middle ger areas and shift peripheral ger districts to private housing schemes by 2030. Central ger districts are those located closer to apartment districts and are under an initial assessment for further infrastructural re-development. Some twelve target areas were assessed for needs, and construction work to shift ger settlements into apartment options is ongoing.[9]

Figure 1: Ger district sections. Aqua blue- river basin, bright orange-central ger areas, orange-middle ger areas, yellow-peripheral ger areas, grey-the city, green-green areas/camp zone. Source: Ulaanbaatar City Development Strategy-2020 and Development Trend till 2030.

Exploring social exclusion in ger districts

Efforts towards increasing citizen participation at all levels has been proclaimed in Mongolia in several key strategic documents, including Direct Democracy and Public Participation.[10] However, people in peripheral urban areas have often been left out of the loop. Households in isolated ger districts are predominantly migrants from rural provinces who face social exclusion from services as well as social relationships at some level. This is the conclusion reached through a recent feasibility study myself and several research assistants conducted in April 2014 in the peripheral ger districts of Chingeltei and Songinokhairkhan in Ulaanbaatar. This survey, funded by the Central Asia Research and Training Initiative (CARTI), covered 80 households and 10 unit leaders.[11]

Searching through literature on social exclusion, social angles of social exclusion have often been given a low priority in exclusion studies. Urbanization is rapidly taking place in Mongolia, where local residents are affected by environmental and social issues. Primary studies of ger districts in Mongolia have described characteristics of growing urbanization and poor socio-economic conditions. However, these studies have lacked an in-depth perspective on the accessibility of social services and existing social relations that allow or hinder community changes. Conducting this study helped to fill this knowledge gap. The findings of this research can help to raise awareness about exclusion, and increase the role of community work in the ger districts.

In general, social exclusion is a multidimensional phenomenon and there are numerous definitions that explain it from differing angles. From the social point of view, an individual is socially excluded if he or she does not participate in certain key activities to a reasonable degree over time in his/her surrounding, and (a) this is for reasons beyond his/her control, even if (b) he or she would like to participate.[12]

We took ideas from what was typically used in other social exclusion studies, as well as developing several “local” questions. These focused on service accessibility issues such as access to public transportation, emergency facilities, land privatization services, as well as access to information in connection to the residential address system. Below are some results of the survey that explores social exclusion that households in target ger districts face:

1. Local residents are excluded from mainstream society due to a limited accessibility and availability of public transportation services to peripheral areas.

A lack of availability and limited accessibility to local transportation services is one of the most highly debated topics when it comes to suburban Ulaanbaatar. Thus, a question of public transportation accessibility and availability was asked as an indicator to measure exclusion from services. Comparatively few households own private cars and public transportation is used on a daily basis as a main means of transportation. However, people have to walk about 500m to 1km through fairly complicated, unpaved pedestrain roads to reach to the closest bus stops. These unpaved roads get muddy after rain, icy in winter and are hilly. Plus, they lack adequate street lights after dark. The availability of public transport is also a problem. For example, only one bus has been serving Takhilt area of Songinokhairkhan district with a 50-60 minute interval between buses. In addition to the difficulty accessing the bus station, there is no running water in the ger districts. Almost 50% of participants complained about walking far to carry water from wells through unpaved roads which are also hilly, muddy and icy.

It was striking to know that 84.8% of survey participants would reach the nearest point of medical emergency assistance by walking about 500m to 1km. When it comes to medical emergency situations, this distance is quite far for people who are dependent primarily on public transportation.

2. Community members’ have limited access to bank credit due to complexity in owning land.

Despite the existing legal environment, roughly half of ger residents in all nine districts of Ulaanbaatar have no official ownership of their plot of land. This stops them from using their land as collateral to gain bank credit.[13] As reported by the Government of Mongolia, by 2013 about 11.8% of the total population and only 7.5% of Ulaanbaatar residents have had their land privatized for their personal as well as for family use since the approval of the first Land Law in 2002. The reason behind this slowness is two-fold, from both the supply side and the demand side. Firstly, many respondents undervalued private land and were not aware of the official procedures for ownership approval that they need to follow, or said they would follow it once forced by a government official (personal communications with ger residents, 2014). Secondly, it is also due to a lack of government policy and programmes that promote ownership of land and the incentives to own it. Owning land and having access to bank credit is particularly challenging for migrant households who have not gained city residency permits and who are not adequately knowledgeable about the paperwork processes they are required to follow. Additionally, apartment prices have skyrocketed and are limited to only those who can afford to rent apartments or afford purchase prices.

3. Accessibility is limited by territorial disorganization and a poorly developed address system

Due to unclear community boundaries coupled with a poorly developed address system, residents in isolated ger districts miss regular information and the visits by unit leaders. It was claimed by some unit leaders that they accidently find a household registered at the first street in the third street, which complicates their weekly visit for the dissemination of information, as well as proper statistics of people’s residency. Public officers such as social workers and unit leaders blame local residents for being passive – about not raising the issue of an incomplete or duplicated address system to the local administration. They generally stereotype them for being ignorant of ways to improve their living environment, and describe them as lazy and dependent on the state. On the contrary, local residents blame the Government for being inattentive and not improving the organization of communities. Ultimately, such a contradictory reciprocal situation creates an atmosphere where “everyone is to blame, but no one is responsible” in the process of ger district development.

4. Residents need institutions to advocate for them, so their voices are heard by decision makers and so they can participate in public events for community improvement.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are key institutions in supporting residents living in isolated areas and assisting in making sure their voices are heard by decision makers. In social exclusion studies, a lack of NGO activities in respective areas and lack of opportunity for local residents to participate in NGO initiatives are used as an indicator for social exclusion. In this study, we asked about peoples’ awareness of local NGOs and about peoples’ participation in NGO activities. About 74.1% of survey participants responded that they did not know of a single NGO. Additionally, 72% of participants had never participated in an event organized by a NGO even though they do not see any barriers limiting their participation. In general, it is certainly a challenge to obtain information on civil society organizations functioning in Mongolia and, thus far, we have limited information of their collaborations and joint struggles due to a weak cooperation between state and civil society organizations. It is estimated that there are nearly 16,000 officially registered NGOs in Mongolia, but only a number of these NGOs work to support migrant households in Ulaanbaatar in accessing better public services such as health, education and employment.[14]

Bayartsetseg’s contact email is: bayartsetsegt@gmail.com

References

[1] Gantulga, 2010; Narantuya, 2010; Byambadorj, 2011.

[2] Munkhjargal, 2006.

[3] Narantuya, 2010.

[4] The total population of Mongolia is 3,022,685 as of the latest data available in 2015. Population of Ulaanbaatar city is about 1,372,042, which is a little over the half of total population. The information was retrieved and updated from www.1212.mn on November 2014.

[5] Ulaanbaatar Statistics Office, 2015.

[6] Information was retrieved from Ulaanbaatar City Statistics Office website at www.ubstats.mn.

[7] Munkhjargal, 2006.

[8] City Mayors’ Office, 2014.

[9] Personal communication with Mr. Enkhbaatar, specialist at the Ger Area Development Bureau, 2015.

[10] The Presidents’ Office (2013). Direct Democracy and Public Participation. Second edition. Ulaanbaatar

[11] Unit leaders – reach-out officers representing government deals – have been the main connector and facilitator of community actions at most occasions. Each district is divided into sub divisions (khoroos) and sub divisions are divided into units/plots (kheseg). Each kheseg or units have a designated unit leader who is responsible for disseminating information and collecting primary data for social workers by visiting door to door throughout his/her designated unit.

[12] Burchardt, 2000.

[13] MCC, 2013.

[14] Personal communication with Ms. Erdenesuvd, NGO representative, 2014.

Close

Close