Subjective realities in divided Nicosia

By Camila Cocina Varas, on 13 December 2017

As part of the DPU summerLab workshop series, the workshop “Inhabiting Edges” took place in Nicosia, Cyprus, during September 2017. The workshop was led by Camila Cociña and Ricardo Martén (DPU) and Silvia Covarino (Girne American University), and aimed to explore and critically understand the history and politics of Cyprus’ borders, navigating the complexities of the last divided capital city in Europe. In this series of two blogs, Bethania Soriano and Sharon Ayalon -participants of the workshop- reflect on subjective realities, developmental disparities, and regeneration processes in divided Nicosia.

By Bethania Soriano and Sharon Yavo Yalon

This post draws from our DPU SummerLab experience in Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, which is considered the last divided city in Europe.

The SummerLab provided the opportunity to challenge preconceived notions of the oversimplified reality that centres around a dichotomised conflict pitting Greek-Cypriot against Turkish-Cypriot. By engaging with the materiality of the city and its social networks, we attempted to uncover nuances and complexities in a context of deep-seated division, territorial and politico-ideological contestation. We were interested in framing division and its impact from the standpoint of the actors that cross Nicosia’s visible and invisible thresholds in an attempt to meet the ‘other’, forming unlikely allegiances to build a sense of identity that bridges fault lines in their landscape. Thus, we conducted fieldwork, collecting different perceptions on belonging and uncovering particularly situated narratives.

Exploring both sides of the divided city, we recognised that the agents who productively engage with difference were mostly young artists, not only from the expected majoritarian ethnic groups, but from an international expatriate community that congregate in Cyprus. As a young musician told us:

“My father is Cypriot; I grew up in Colombia, Chicago and then in Cyprus.

People from all over the world live here. This is Cyprus – we are cluster-f***ed.” 1

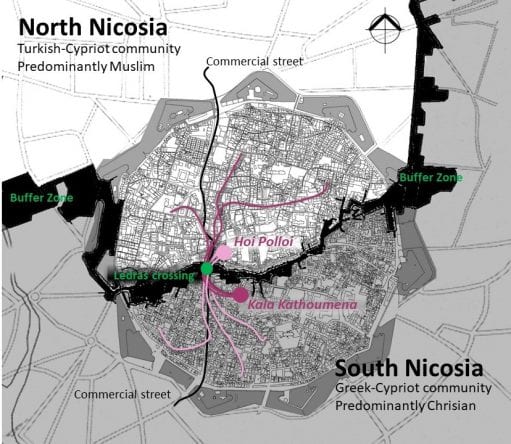

Thus, we discovered shared spaces of ‘encounter’ such as the two twinned cafes, Hoi Polloi in the north, and Kala Kathoumena in the south, as the gathering places of the artistic community on each side of the buffer zone – areas emblematic of tolerance and sought-after common ground. The informal interviews conducted in these spaces highlighted, in the evocative and charged language used by the interviewees, the importance of capturing voices beyond the well-known register – those whose stories will not feature as officially promoted, sanctioned narratives.

Location of café’s and interviewees routes showing southerners crossing to the north and vice versa.

When asked to comment on the prevailing mentalities from people in the north and south, a young British-Filipino singer articulated her thoughts in a candid way, disconcerting in its lyrical tone:

“… the south is a ‘rock’, whereas the north is like ‘air’.

In the north people are chaotic, relaxed, middle-eastern… when we play, they dance and smile back at you. In the south people are serious and philosophical, more reserved and conservative… and really scarred by what happened.” 2

Reflecting on the young woman’s comments, the south is portrayed anchored in the solidity and rigidity of the perceptions and views of its inhabitants; in the reaffirming and reinforcing of memories and official narratives of occupation and suffered injuries.

“In the cover of all school notebooks, there are these slogans – ‘Do not forget’. The school books are all branded, so we are constantly reminded…” 3

Whereas in the north, the rarefied and ephemeral re-imaginings of identity and belonging are expressed in the ways people wish to highlight and confront narratives of prejudice:

“People from the south think in the north you can get raped… they [Turkish-Cypriots] will steal your children.” 4

Motivated by the need for political survival against the longstanding embargo and isolation from the international community, many Turkish-Cypriots are interested in carving a sense of collective Cypriot identity that includes southerners. Even if that involves selective forgetting of past injuries, some are choosing to ‘draw a breath of fresh air’ in order to survive:

“…it is important to move from a narrative of ‘This is who we are’, to a narrative of ‘We do not know who we will become’… ” 5

However, across Nicosia diverse voices can be heard. Alongside few Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots who dared to venture beyond rigid confines and shed some of the values of their communities, others were conflicted:

“Now I realise that I only had half a childhood – I only met half the people I could have… only made half the friends… only had half the experiences.” 6

“I tried to cross with my friend and we walked all the way… but when my friend saw Ataturk [statues] and all the [Turkish] flags he got scared and turned back.” 7

“Before the [Ledras Street] crossing, people never thought the south was so ‘close’ – there was an initial shock; then the shock of all the similarities!” 8

Hoi Polloi in the north, and Kala Kathoumena in the south.

In conclusion, the quotes reproduced above testify to the individuals’ ingenious capacities to articulate, negotiate, ascribe meaning and ultimately either normalise or contest the ‘everyday’. Their struggles for belonging co-exist with the need to develop and affirm an identity, breaking away from any restrictive ‘cluster’ to reclaim their place in the city. Whilst examining Nicosia’s overlapping, subjective realities, we learned that identity is not necessarily bound by place, but it is relational and situated – it can only be conceived in regard to the material reality of place and its sustaining social networks. Identity is also fluid and in constant transformation.

- Young Colombian-Cypriot man who grew up in the United States and Cyprus; artist.

- Young British-Filipino woman, in Cyprus for the past 17 years; living in south Nicosia and working as an artist and singer in north Nicosia.

- Young Greek-Cypriot aspiring artist, living in the south and frequenting the artists’ cafés in north Nicosia.

- Turkish-Cypriot male student, commuting from Kyrenia/ Girne into north Nicosia.

- Dean of Architecture, Design & Fine Arts at Girne American University, Assoc. Prof Dr Mehmet Adil,

addressing participants of the SummerLab.

6 and 7. Young Greek-Cypriot man, living in south Nicosia and often visiting the north side.

- Mayor of North Nicosia, Mehmet Harmancı, addressing participants of the SummerLab.

Bethania Soriano is an independent researcher based in London, particularly focused on the politics of contested spaces – the ways in which people negotiate the environments they inhabit, adapting, reclaiming and ultimately shaping space by virtue of their everyday practices. She studies areas with long-established ‘geographies of difference’, in contexts of conflict transformation, and where minorities strive for spatial justice and social inclusion.

Bethania trained as an Architect and Urban Designer in Southern Brazil and holds an MSc in City Design and Social Science with distinction, from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Sharon Yavo Yalon is a lecturer and PhD candidate at the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, based in Haifa. Her research enfolds the linkage between art and urbanism and the manner in which local identity, spatial (in)justice and social (ex-in)clusion are forged or deconstructed by artistic activity in cities. More specifically, she focuses on artistic interventions in contested cities and the ways in which they affect and are affected by urban segregation patterns and boundaries. Sharon is a practicing architect and artist, graduated summa cum laude BA and MSc in Architecture and Town Planning from the Technion IIT.

Close

Close