Power and Politics: A reflection on political settlement

By Michael Walls, on 11 April 2016

To many – perhaps more today than in some generations past – ‘politics’ is a dirty word. Yet the political permeates our social lives on the most personal of levels as well as more generally. And the twin sibling of politics is power; specifically it’s exercise and pursuit. Perhaps the thing that most upsets many of us about ‘politics’ is what we perceive as the naked or covert use of power for personal betterment. But there’s a complication there. As much as we tend to presume that unbalanced power is a bad thing, the reality is that the stability of human societies through history and around the globe rests on just such imbalances. And personal interest occupies an uneasy yet always central motivator in the exercise of that power. In some ways, it is hard to even conceive of power in terms other than in some unbalanced sense. After all, if one person possesses the ability to compel someone else to do something, then that represents an imbalance in itself. There’d be no compulsion if the person compelled didn’t accept the authority of the other. Which highlights the difficult balance we need to try and find as human societies if we are to balance some sense of social justice with the sort of systemic efficacy we must aspire to if our states are to be run with reasonable efficiency.

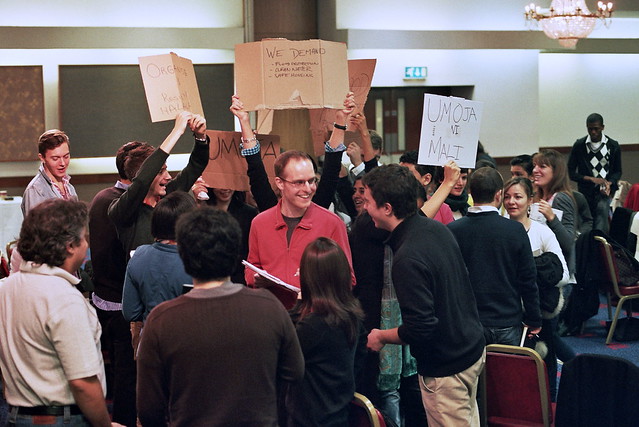

Political leaders sign an agreement on voter registration, Hargeisa

The idea of the ‘political settlement’ that lies behind this project encourages examination of the nature of those balances in the political realm.

But we can also think of power in different ways. The sense of power as an imbalance in which one person can compel another, which I’ve just described, is what Andrea Cornwall and John Gaventa called ‘power over’. But we also sometimes think of power in different terms. For example, the power to do something is usually more about the capacity we have to act, and we sometimes also talk about ‘inner’ strength; the power we gain from within ourselves. Not quite the same as the capacity to do something because it refers more to strength of character or resolve, but that can connect with capacity as well. There is also a sense of power that labour unions, amongst others, have often used: the power of unity or solidarity. The power we gain by working together with others of like mind.

Focus group meeting in Laas Aanood

The ‘Political Settlement in Somaliland‘ research project is designed to dig deeper into some of the attitudes that women and men have to each other’s political engagement, and to find out more about how those attitudes are reflected in the ‘political settlement’ that underpins what has become an enduring peace in Somaliland. In so doing, we will be thinking hard about how different kinds of power are exercised by women and men in Somaliland: both in the negotiations, debates and decisions that form the political settlement, and in the actions people take or have taken in an effort to influence those decisions.

It is axiomatic that one of the most persistently asymmetrical balances of power is where it relates to the roles of men and women in a society. A growing body of research has focused on Somali state-building, and particularly on Somaliland, and there have been a number of studies on gender roles in that context. We are aiming to explore the ideas at the intersection of those concerns by trying to understand more about the assumptions and positions that shape social relations for men and women. That links strongly to a number of specific areas, including violence against women and girls, which seems to have worsened even while stability has been consolidated.

We are still in the relatively early days of the research, and are currently collecting primary data. There’ll be numerous updates of one sort or another. Keep an eye on the research microsite for new material.

Drawing water for camels from a well, Sanaag

Dr. Michael Walls is a Senior Lecturer at UCL’s Development Planning Unit (DPU) and Course Director for the MSc in Development Administration and Planning. He has twelve years’ experience in senior management in the private sector and lectures in ‘market-led approaches to development’. For some thirteen years he has focused on the Somali Horn of Africa, and most particularly on the evolving political settlements in Somaliland and Puntland. He is currently leading a research project focused on developing a gendered perspective on Somaliland’s political settlement. As well as undertaking research on state formation and political representation, he has been a part of the coordination team for international election observations to Somaliland elections in 2005, 2010 and 2012 and is currently observing the 2016 Voter Registration process.

Close

Close