Megacities are bad for the developing world

By ucfuvca, on 5 July 2013

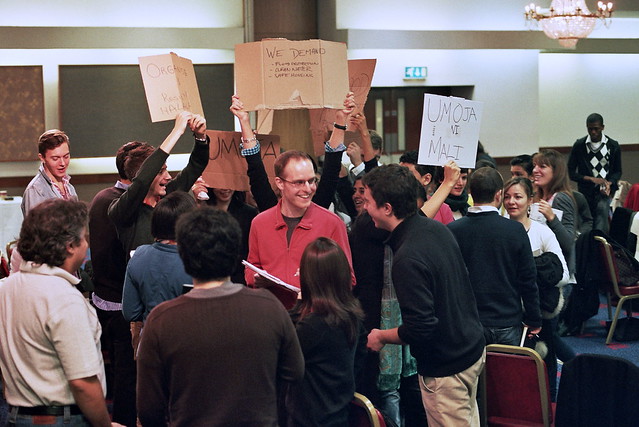

This is an extract from the talk given to the finalists of Debating Matters, National Finals 2013 at UCL, London. Debating Matters is a competition for sixth form students, organized by the Institute of Ideas. For more information about Debating Matters, please see: http://www.debatingmatters.com/

Megacities may not be bad for the developing world in every sense. They concentrate population, resources and capital… they may support regional and national economies. However, I want to argue here that ‘Megacities are bad for the developing world’ in the sense that they constitute a threat to the dreams and aspirations of most urban citizens in the global south. In particular, I am worried about the extent to which megacities draw opportunities away from ordinary citizens and expose them to disproportionate risks.

When walking through tall cities of glass towers I do not experience the buzzing atmosphere that one would expect from the concentration of people. Think for example of walking in the city of London on a Sunday afternoon. These are empty, ghost landscapes- functional spaces where people do not live.

In Shanghai, the expansion of the glass city, for example, is threatening the traditional alleys, called Longtangs. To understand life in a Longtang you have to imagine beautiful narrow streets full of activity, with vendors, workers wandering, children running, elderly playing board games and most of all, the symbolic hanging of the clothes to dry. When walking through Shanghai Longtangs I was mesmerized. But when one of the residents said that they were being evicted to make space for glass towers I was sad to imagine those beautiful places, created through centuries of interaction between human and their environment, displaced by empty, glass buildings, monuments to human egos, rather than to human kindness and civilization. This cannot in any sense be a model for our future cities.

When cities are regarded only as giant reservoirs of labour, people suffer. This is because, although work is important in people’s lives, people do more than just working. They may be obliged to be in cities if work is there, but cities have to offer as well quality of life and services including access to resources such as water, sanitation and energy and access to education and health.

UN-Habitat estimates that “over the past 10 years, the proportion of the urban population living in slums in the developing world has declined from 39 per cent in the year 2000 to an estimated 32 per cent in 2010”. They argue however that “the urban divide endures, because in absolute terms the numbers of slum dwellers have actually grown considerably, and will continue to rise in the near future.” UN-Habitat estimates that the world’s slum population is expected to reach 889 million by 2020. Even in mega-cities where the proportion of informal settlements has been reduced- especially in Asia- this has been done through evictions and relocations which destroy people’s lives and are hardly reflected in the official statistics.

While the availability of capital may make it possible to complete big infrastructure projects, these projects are unlikely to benefit the majority of the urban population, least of all the urban poor. Take the express highway in Mumbai to check this. While the center of the city is difficult to navigate, because of the continuous flow of people on foot, bikes, motorbikes and other vehicles, this highway is empty. A toll fee becomes a means to prevent the large majority of the people in Mumbai from using the highway, thus giving the richer people the privilege of traveling in less time. Scholars have described this kind of process as a form of “splintering urbanism”. “Splintering urbanism” means that in large urban centers, specially megacities, infrastructure services concentrate in wealthy areas and move away from poorer ones, leading effectively to the fragmentation of service provision. This limits the access of the underprivileged and the working class to basic services. Infrastructure may even pass through the houses of the poor but they lack access to it

The splintering of service provision is also related to resource scarcity. Megacities are often treated as isolated islands of prosperity. But the truth is that this prosperity depends on huge imbalances between the megacity and the broader regions that the city depends upon. These rural-urban imbalances draw giant flows of people and resources that may further impoverish rural areas. Moreover, megacities may export their residues they cannot deal with. In the past, these relationships have led to the vision of the city as parasitic. Cities are not parasitic, they are essential ways of organizing human life, reservoirs of creativity. But when massive growth- both of population and resources- is promoted at the expense of the larger regions where the city is located then there is a danger that this parasitic metaphor becomes real.

Take for example how mega cities are encroaching in their immediate natural environment. I call this “the paradox of the eternal suburb”. On the one hand, middle class urbanites go to the periphery in search of more relaxed forms of life, idyllic dreams or ruralized living and greater contact with nature. On the other hand, this search leads them to destroy the very environment upon which the city depends. For example, there has been in recent years a proliferation of eco-cities in Bangalore, India. Most of them are being built at the urban fringe in gated communities, hosting quite wealthy sectors of the population. Under the premise of eco-cities and using green technologies such as wind energy and solar panels, they draw on the land and water resources that belong to the whole city. Worse enough they are threatening the wildlife landscapes that surrounded the city. When I talked to one of the developers on the construction site of an eco-city she told me that only a few weeks before, in the same spot where we were standing, she had seen a tiger. ‘We are so close to nature!’ she said. I asked her whether she was not worried that their projects were destroying the natural environments upon which these tigers depended. ‘If we were not building this, other would come and would do something worse’, she said. But, to what extents do tigers mind about solar panels or wind energy?

All these issues become now magnified by climate change. The pressing nature of climate change highlights the importance of considering seriously how megacities concentrate risks. Not only populations in megacities are exposed to climate change, but also, its impacts affect mostly the urban poor. The urban poor are often settled in areas with the highest risks, whether this is in flood prone areas or in areas affected by other risks. When floods struck Florianopolis, Brazil, in November 2008, 84 people die and 54,000 were left homelessness. Most of these people had not choice but to live in dangerous slopes where their houses became engulfed by mudslides. The vulnerability of the urban poor to climate change also determines that their reduced capacity for response and after a disaster such as this, their only option may be to continue living under the shadow of risk or move to even more dangerous areas.

Some have pointed out at megacities as providing solutions to mitigate climate change action. They claim that the key to reducing carbon emissions is achieving higher urban densities and promoting the concept of the compact city. But urban growth is highly heterogeneous. In most megacities, urban sprawl- rather than density- is the main feature. In megacities sprawl is only contained by the geography, such as it happens in Mumbai, where the impossibility of growing beyond the water has led to an increase in density at the expense of the cities mangroves- hence increasing the vulnerability of the city to climate change risks and natural disasters exponentially.

What are the best means to achieve high density? People living in informal settlements have demonstrated how they can achieve high densities by occupying urban space, rather than just by growing up vertically. In other places, like in Spain, higher density is achieved by moderately tall constructions, because the habitability of the city. Rather than conjuring visions of megacities, these examples speak to balanced, diverse cities which acknowledge the location of cities within a rural-urban continuum and that provide space and opportunities for all urban dwellers to reach their aspirations.

While high rise may have actually brought about higher densities in cities such as Hong Kong this has been at the expense of their vulnerability to climate change risks, especially heat waves. Moreover, the gains in reducing carbon emissions that follow high density may be small in comparison to the additional carbon emissions produced by the need to manage the emerging risks.

Ultimately we have to ask: what is a megacity and why we need them? They may contribute to bring together a disproportionate share of capital and build labour reservoirs. In doing so, megacities represent nodes in global financial and knowledge flows, rather than places for ordinary people to live their lives.

Vanesa is a lecturer at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit.

Close

Close