Seasons Greetings from the Survey of London

By the Survey of London, on 21 December 2018

Thank you for reading the Survey of London’s blog posts over the last year. Here follows a selection of our favourite wintry photographs from our past and present studies of London. Happy Christmas and all good wishes for the New Year.

Oxford Street

As the longest continuous shopping street in Europe since the eighteenth century, Oxford Street is a unique phenomenon. Though it has witnessed almost continuous change, it has never lost its popularity. The character of Oxford Street is defined above all by its shops, and Christmas is its busiest time of the year. In 2015 we asked Lucy Millson-Watkins to photograph the lights, sights and decorations of Christmas on Oxford Street. Here is a selection of the photographs that she took, first published online in a blog post that considered the festive season on Oxford Street and its enduring traditions. The Survey’s work on Oxford Street is nearing completion, and the volume is expected to be published by Yale University Press, with support from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, in 2020.

Boots at 385–389 Oxford Street, photographed in December 2015. (© Lucy Millson-Watkins)

West end of Oxford Street looking towards Marble Arch, with Marks & Spencers flagship store. (© Lucy Millson-Watkins)

The Toy Store at 381 Oxford Street, a Dubai-based chain which opened its first UK store in 2014 close to Bond Street Station. (© Lucy Millson-Watkins)

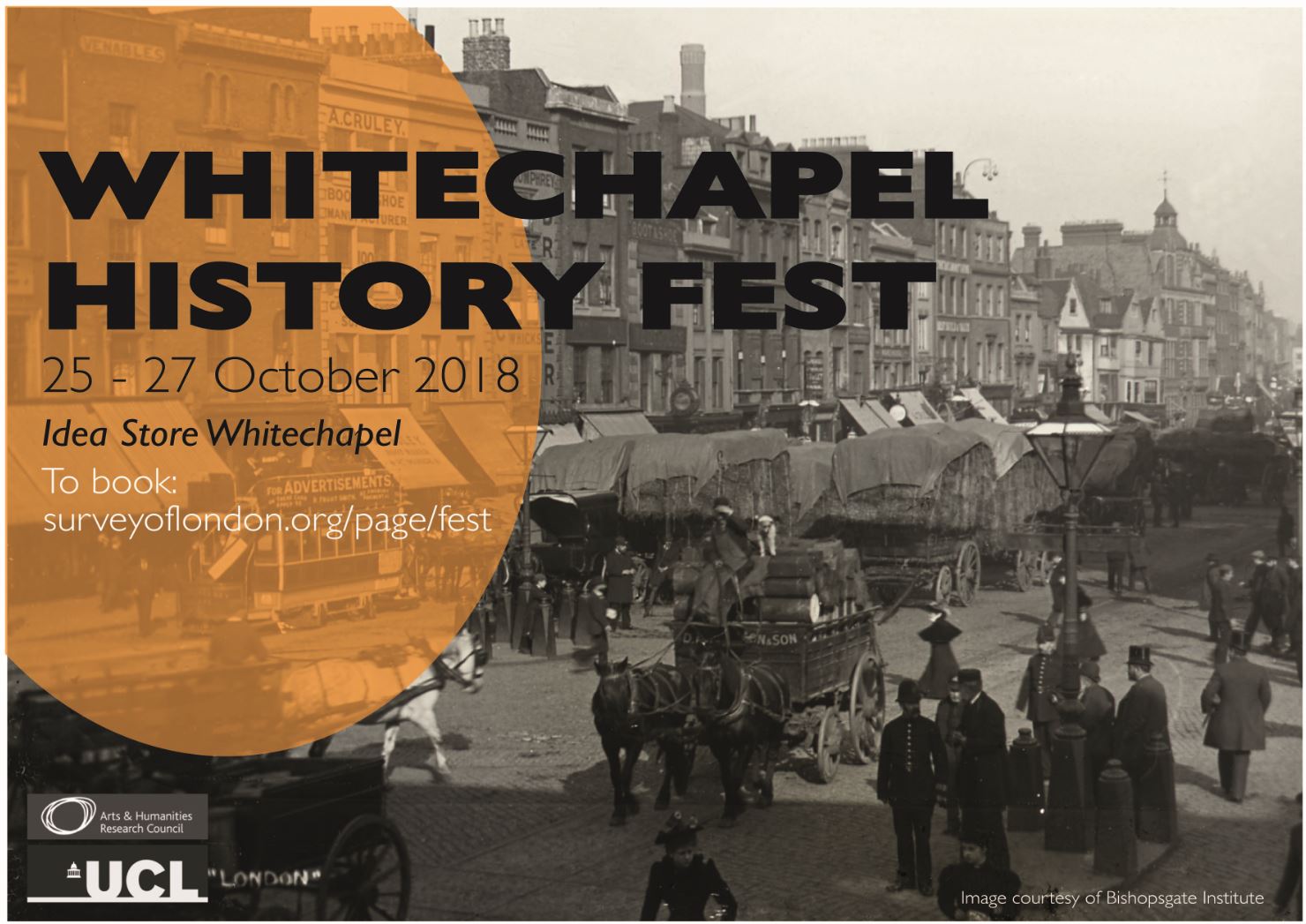

Whitechapel

Research is continuing in Whitechapel, a district with a long and rich history, currently in the throes of intense change. One of this year’s highlights for the Survey was the Whitechapel History Fest, which took place at the Whitechapel Idea Store in October. The festival marked the closing stages of the three-year Arts and Humanities Research Council funded research project, ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Local experts, residents and historians convened to discuss the past and present of Whitechapel, with talks, film, poetry readings and panel discussions.

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 32–34 Whitechapel Road, in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Gee 8 Fashions, 14 New Road, Whitechapel, photographed in November 2018. (© Derek Kendall)

View into vehicle dispatch bay at the East London Mail Centre and E1 Delivery Office, Whitechapel Road, photographed in October 2018. (© Survey of London, photographed by Derek Kendall)

South-East Marylebone

In 2017, two volumes (Nos 51 & 52) were published on South-East Marylebone, covering a large swathe of the parish of St Marylebone. In November 2018, the Survey was honoured to received the prestigious Colvin Prize from the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain in recognition of the volumes as an outstanding work of reference on an architectural subject. The draft chapters are available to download via our website, pending a full online version. The Survey is following up these volumes with a study of South-West Marylebone, covering the area west of the boundary of the previous volumes as far as Edgware Road.

17–18 Cavendish Square, view from the east in December 2015. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The Golden Eagle Public House, 59 Marylebone Lane, view from the north-east in January 2016. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nativity with six apostles on the lowest row of the reredos at All Saints Church, Margaret Street, South-East Marylebone. The tilework at All Saints was designed by Butterfield, painted by Alexander Gibbs and executed by Henry Poole & Sons. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Battersea

The Survey completed its work on Battersea in 2013, with the publication of two volumes (Nos 49 and 50) by Yale University Press. The draft texts of all thirty-two chapters from the Battersea volumes are available via our website, prior to the release of a full online version.

Battersea Square, photographed in December 2012. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Clapham Common under snow in 2013. St Barnabas’s Church on Clapham Common North Side is within view in the distance, its pitched roofs adorned by a dusting of snow. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Clapham Common under snow in 2013, looking towards towards Clapham Common North Side. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Woolwich

Finally, 2018 saw the online publication of the Survey’s volume (No. 48) on Woolwich, first published in 2012 and now digitally available here.

Woolwich Covered Market, Plumstead Road, listed in 2018, photographed in 2007. (© Historic England, Derek Kendall)

Mosaic detail from St George’s Garrison Church, Woolwich, photographed in 2007. (© Historic England, Derek Kendall)

Mosaic and painted decoration, St Michael and All Angels Church, Woolwich, reconstruction. (© Historic England, George Wilson)

Dan Cruickshank’s photographs of Whitechapel and environs in the early 1970s

By the Survey of London, on 30 November 2018

This is a post of photographs arising from the Survey of London’s Whitechapel History Fest, held at the Idea Store Whitechapel in late October. The event drew more than 200 people to attend a range of talks and discussions, as well as poetry readings and the premiere of a film. We were delighted that Dan Cruickshank came to present the final talk of the occasion, a wide-ranging overview of Whitechapel’s history from a personal point of view. He recounted his walks through the wider E1 area in the early 1970s, using his own photographs of that time as illustrations. Dan has now kindly shared these and a number of other contemporary photographs with us. All images are the copyright of Dan Cruickshank.

185 and 187 Whitechapel Road

23-25 Parfett Street, Whitechapel

Lambeth Street, Whitechapel

Former sugar refinery, converted to tea warehouse, Dock Street, Whitechapel

Brushfield Street, Spitalfields

Sclater Street, Spitalfields

Fleur-de-lis Street, Spitalfields

St Katharine’s Dock warehouses

London Dock and warehouses

London Dock warehouses (Pennington Street or north side)

America Circus

Staircases in South-East Marylebone

By the Survey of London, on 9 November 2018

Earlier this week, the Survey of London team was honoured to receive the prestigious Colvin Prize from the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain, for two volumes (Nos 51 and 52) covering south-east Marylebone. This blog post follows an earlier exploration of doorcases in that area, which has remarkable richness and variety in its history and architecture. We would now like to present an assortment of staircases, photographed by Chris Redgrave and Lucy Millson-Watkins as part of the study.

Dignified Edwardian blocks designed for entertainment and shopping such as the Wigmore Hall (1900–1), the Berners Hotel (1905–11) and the former Debenham & Freebody store (1906–7) contain luxurious staircases in marble-clad halls. More variety is to be found in buildings designed as private residences, including an original decorative scheme by Arthur Beresford Pite at 37 Harley Street (1897–9), and sleek interwar glamour and high-quality materials at 39 Weymouth Street (1936). The architect there, G. Grey Wornum, oversaw the design of the new RIBA headquarters at Nos 66–68 Portland Place (1933–4), which has a dramatic staircase dominated by giant fluted marble columns.

Practicality and economy are in evidence at the Western District Post Office in Rathbone Place (1956–65, demolished), which had a staff of more than a thousand. The metal staircase of the Central Synagogue in Great Portland Street (1956–8) is also utilitarian, but with a touch of glamour in its angular detailing. The staircase of 99 Mortimer Street, a converted terraced house occupied by stringed-instrument dealers since the 1940s, is modest in its size and pretensions.

Staircase at former Debenham & Freebody store, 33 Wigmore Street. The south side of Wigmore Street offers a sudden change in scale and monumentality with the silvery bulk of No. 33, built as headquarters for the drapery business of Debenham & Freebody in 1906–7 to designs by architects William Wallace and James G. S. Gibson. Internally, the decorative scheme for the building was unusual but luxurious, with grey and green marble setting the tone in the entrance hall and room above – in the columns framing the staircase, the stair treads, ceiling ribs, floors and walls. The bronze work was by Singers of Frome: balusters, handrails, gallery railings and the capitals to the columns supporting the vast showrooms. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

39 Weymouth Street is one of the 1930s rebuildings in the area by Bovis Ltd, in this instance the work of G. Grey Wornum, the architect of the new RIBA headquarters on Portland Place. That commission won him renown for spatial dexterity and commitment to high-quality fittings, qualities apparent in this interesting house. Wornum’s involvement is not readily discernible from the rather staid Georgian-style frontage, but his hand was to the fore inside. Although the house is not listed and has been modernized on several occasions, its interior retains much of the character and some of the features of his original design, such as this curved staircase in the hallway. The first resident from 1936 until the 1950s was Thomas Lyddon Gardner, chairman and managing director of the Yardley Perfumery and Cosmestics Company, and it is possible that the house was designed specifically for him through Bovis. Pictures of it newly finished were reproduced in the Architect & Building News in 1936. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

37 Harley Street is one of the major surviving works in Marylebone by the versatile architect Arthur Beresford Pite, and exhibits his powerful originality. Dating from 1897–9, it was one of several commissions of that period in Marylebone where Pite was associated with the local builders Matthews Brothers. A small iron bay window, projecting into the internal area, was added to the first-floor landing at the suggestion of Matthews Brothers. Pite ornamented the window with decorative leaded lights in coloured glass. For a fuller account of 37 Harley Street in an earlier blog post, please click here. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Western District Post Office (demolished), Nos 35–50 Rathbone Place. This was planned soon after the Second World War to replace two of three existing West End offices, connected with the Post Office Underground Railway. Designs for the building were reworked in 1960 by Alan Dumble, a senior architect in the Ministry of Works, and the new office was opened on 3 August by the Postmaster-General, Anthony Wedgwood Benn. The new postal office was among the most mechanized in Europe, with chain conveyors in the sorting halls and spiral chutes to despatch mail down to the railway, and its opening coincided with the introduction of both postcodes and electro-mechanical sorting machines. Even so, the fourth-floor canteen and other facilities served a staff complement of more than a thousand. A reconfiguration in 1974–6 provided a bar, games room and lounge, and incorporated stained glass and war memorials salvaged from other post offices. For a full account of the Western District Post Office in an earlier blog post, please click here. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Central Synagogue, Nos 131–141 Great Portland Street, was built to designs by C. Edmund Wilford & Sons in 1956–8, replacing its bomb-damaged predecessor of 1869–70. Wilford had made a name with cinemas before the war. He and his assistants were directed to look at synagogues in London and perhaps also Venice. The result, built by Tersons Ltd, was a conventional, dignified building with close correspondences to its predecessor but an internal touch of cinematic glamour. The Great Portland Street façade is clad mainly in Portland stone, but the plinth and the columns flanking the high and hooded windows are of red Swedish granite. At the north end the entrance doors are set back in a high frame covered in gold mosaic. The galleried interior gives a powerful impression of height and restrained opulence, with a focus on the ark at the south end. For more photographs of the Central Synagogue in an earlier blog post, please click here. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

7 Cavendish Square replaced a nineteenth-century successor to the original early eighteenth-century house. In 1908 Frederick John Dove negotiated an 80-year rebuilding lease, undertaking to erect a ‘mansion’. This was done through his family firm, Dove Brothers Ltd, but he was probably acting on behalf of Alfred Ridley Bax, FSA, the first occupant of the new house. It was built in 1909–11 to designs by the architect James G. S. Gibson, a vice-president of the RIBA when he took the job. Bax, a wealthy non-practising barrister, local historian, homeopath and father of the composer Sir Arnold Bax and writer Clifford Bax, moved here from Hampstead and died in 1918. As a domestic building, No. 7 is a rarity in Gibson’s work. It has more classical or Beaux Arts restraint than his usual Baroque Revival manner, perhaps a nod to the context of the square. Inside, the house was given fireproof floors and roofs and a mahogany-panelled lift. A shapely cedar-panelled staircase sweeps up the hallway in curves reminiscent of the stairs in Gibson’s contemporary Middlesex Guildhall. It rises to the second floor with intricately patterned, open-work balustrade panels carved by Dove Brothers. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

19 Portland Place was one of several houses in the street to be leased to the plasterer Joseph Rose. The Rose plasterwork extends to the stairwell, where there are scallops and garlands around the skylights, as well as guilloche bands and wall arabesques containing moulded plaques of dancing bacchantes and other classical figures. Early residents here in the 1780s and 1790s included Lord Lisburne and Lady Templeton. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

63 Harley Street is one of the street’s few inter-war houses, having been built in 1933–4 to designs by Wimperis, Simpson & Guthrie for the ophthalmic surgeon Sir Steward Duke-Elder and his wife Lady Phyllis. The façade is understated, blending the proportions and classical elegance of the Georgian house it replaced with Art Deco touches. The interior was a tour de force of thirties design, all sinuous curves and sumptuous wood panelling, brilliantly illuminated by lighting designed by Waldo Maitland. The bespoke fittings included much furniture, from fixed umbrella stands in the hall to desks, filing cabinets and bookcases by Betty Joel. There was also a circular rug designed by Marion Dorn, then at the peak of her career in London. Overall the impression was of a chic American or central European clinic. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Stairs and balcony over the foyer at the Wigmore Hall, Wigmore Street. Tucked away behind the street frontage of Nos 36–38 lies the small but sumptuous Wigmore Hall, built in 1900–1 as Bechstein Hall for Carl Bechstein & Sons, whose showrooms were by then at No. 40. As at the showrooms, the architect was T. E. Collcutt. The entrance passage and foyer were paved in black and white marble and featured, along with the staircase and balcony, dadoes of Numidian marble with red Verona marble edging. With the opening concert on 31 May 1901, the hall was acclaimed as ‘unquestionably the handsomest in London’. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

44 Hallam Street was erected in 1915 to house the General Medical Council. The council had begun to investigate a move to larger premises from its offices at 299 Oxford Street in 1903, but the initiative was not taken forward until a decade later. An enquiry to the Howard de Walden Estate in 1914 elicited the offer of a development site at 44–48 Hallam Street. The northern part of the building was not added until 1922–3. The architect at both stages was Eustace C. Frere, of South African origins and Beaux Arts trained, and the builder Chinchen & Co., of Kensal Green. For a fuller account of the former General Medical Council headquarters in an earlier blog post, please click here. (© Historic England, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

23 Queen Anne Street. The Howard de Walden Estate office was built in 1937 to designs by Ernest Joseph, working in conjunction with the Estate’s in-house architect V. Royle Gould. The exterior of the building, stripped-Classical in style and faced in Portland stone, was designed to blend with 35 Harley Street adjoining. The interior is fairly understated and conservative in taste; its best feature is the staircase, with dark wood handrails and newels, and pale terrazzo treads. Trollope & Colls were the main contractors. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

RIBA headquarters, Nos 66–68 Portland Place. In the entrance hall, it is the staircase that is G. Grey Wornum’s tour de force. It is a dramatic space, dominated and held together by four giant fluted columns of green Ashburton marble, star-shaped in plan and without bases or capitals, that rise nearly 30ft to the coffered glass ceiling. Within them are the enormous stanchions of the steel frame, the elegant proportions of which provided one of the aspects of Wornum’s design greatly admired at the time. As elsewhere in the building, fine materials and craftsmanship contribute to the overall effect, with walls lined in limestone; risers and treads of black Derbyshire and blue Demara marble respectively; and, above all, Jan Juta’s etched-glass balustrade, lit by concealed tubular lights in its base. For more photographs of the RIBA headquarters in an earlier blog post, please click here. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Berners Hotel, Berners Street. The Berners Hotel is a rare instance of continuity in this area. The hotel can be traced back to 1826. In the following year, The Times recorded that a ‘fine double house’ at 6–7 Berners Street had been converted into the Berners Hotel. It was rebuilt on a much enlarged site in stages between 1905 and 1911, under the superintendence of Slater & Keith. To read a full account of the Berners Hotel in an earlier blog post, please click here. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

J. P. Guivier & Co. Ltd, 99 Mortimer Street. This dignified little building of 1899–1900 owes its remarkable state of preservation to its occupancy since the 1940s by J. P. Guivier, stringed-instrument dealers. It was built by Antill & Co. for Charles Kempton, tailor, probably to the designs of the architect A. J. Hopkins, who dealt with the Portland Estate on Kempton’s behalf. J. P. Guivier & Co. Ltd took part of the building around 1947 and have slowly expanded into all floors. Joseph Prosper Guivier, son of Jean Prospere Guivier, an exponent of the ophicleide, had begun his career in London in 1863, importing violin strings. The shop and first-floor front room are showrooms for stringed instruments and accessories, the back extension and upper floors offices and repair shops. (© Historic England, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Bradley’s Spanish Bar at Nos 42–44 has long been one of Hanway Street’s most colourful establishments. The house itself was built in the mid 1860s, and the first commercial occupiers were sewing-machine makers. In 1869 the premises were fitted up as a ‘first class eating house’ with a wine licence, and remained a wine house under successive proprietors for well over a century. By the mid 1890s it was run by Long & Co. and described as ‘a cut above the public house’, serving biscuits and sandwiches with wine. Long’s came into the ownership of Robertson Brothers and Company, port merchants, and in the 1950s of an associated company, Williams & Humbert, one of the leading sherry shippers. Williams & Humbert opened a Spanish bar here (together with an English bar and cellar) around 1959. They sold up in 1966 or 1967 and the wine house continued under Short’s Ltd, being taken over at some point by the Milo twins. By the late 1970s it was known officially as Bradley’s Bar, taking the name of a former patron, William Bradley, a decorative glass-cutter in Hanway Place, who apparently ran a social club for his employees here. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Whitechapel History Fest: 25–27 October

By the Survey of London, on 12 October 2018

The Survey of London is the organiser of a multi-vocal history festival convened to mark the end of the three-year Arts and Humanities Research Council funded research project, ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. This three-day event will bring together a range of local experts, residents and historians to discuss the past and present of Whitechapel at the Idea Store. There will be talks, the premiere of a specially commissioned film, poetry readings and round-table discussions. Contributors include Rachel Lichtenstein, the Gentle Author, Ajmal Masroor and Dan Cruickshank.

Tickets (£5 per day, £12.50 for three days) are available via Eventbrite. You can also follow live updates from the conference by searching for the hashtag #WhitechapelHistFest on Twitter.

Thursday 25th October – 6.30–8.45pm

Avram Stencl: The Yiddish Poet of Whitechapel

Rachel Lichtenstein

This illustrated talk examines the life and work of London’s foremost Yiddish poet Avram Nachum Stencl (1897–1983) who was born in Poland in the late nineteenth century into a rabbinical dynasty. After spending some time in Holland and Germany, he made his way to Berlin in the 1920s where his work attracted the attention of the literary elite, including Thomas Mann. He arrived in dramatic circumstances to London in 1936 and spent the rest of his life passionately dedicated to the preservation of the Yiddish language. Stencl became one of the most familiar figures of Jewish Whitechapel, standing outside the lecture halls, meeting places and cafes, crying out, koyfts a heft! – Buy a pamphlet. He established the longest running literary group in the UK but is now practically unknown. Come and learn more about this extraordinary figure, if you have memories of Stencl to share Rachel would be delighted to hear from you.

Rachel Lichtenstein is a writer, curator and artist. Her publications include: Estuary: Out from London to the Sea, Diamond Street, On Brick Lane, Rodinsky’s Room, Keeping Pace: Older Women of the East End, A Little Dust Whispered and Rodinsky’s Whitechapel. Her artwork has been widely exhibited both in the UK and internationally. Venues include The Whitechapel Gallery, The British Library, The Barbican Art Gallery, Wood Street Galleries (USA) and The Jerusalem Theatre (Israel). She is a Reader in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University, a tour guide of London’s Jewish East End and works as the archivist and historian in London’s oldest Ashkenazi synagogue, Sandys Row.

Poetry Readings

Celeste, Bernard Kops, Chris Searle, and others

Celeste is a teacher and performance artist based in Shoreditch. Celeste presents new works exploring themes of time, place and identity in London.

Bernard Kops was born 91 years ago in Stepney Green. ‘Where my East End streets gave me the strength and chutzpah, the building blocks of my future, my world of writing. So here I am, still alive and working, with the joy of love and living, with my wonder wife of 63 years and enormous family. And my writing, for writing is work, and work is life. And behind me and ahead are my years of drama, poetry and novels.’ He has written some new poems – East End Dreams – for this event.

Chris Searle has written or edited over fifty books on subjects as diverse as education, poetry, language, journalism, cricket and jazz. Among them The Forsaken Lover (which won the Martin Luther King Award in 1973), Classrooms of Resistance, The World in a Classroom, Words Unchained: Language and Revolution in Grenada, Your Daily Dose: Racism and ‘The Sun’, Pitch of Life and Forward Groove. He writes a weekly jazz column for the socialist daily newspaper, the Morning Star. In 1971 he collaborated with Ron McCormick to produce the influential book of schoolkids poetry, Stepney Words, and a number of other projects in East London, most recently Stepney Words III (commissioned by Rich Mix, the Shoreditch media arts centre). Together they produced and published Whitechapel Boy, a reappraisal of the poetry of the First World War poet, Isaac Rosenberg, to commemorate the centenary of the poet’s death in the French trenches in April 1918.

St George’s German Lutheran Church, Alie Street, in 2017, photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Friday 26th October – 10am–5.15pm

At Home in Whitechapel’s Deutsche Kolonie

Sarah Milne

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Whitechapel was home to tens of thousands of German migrants, many of whom were intimately connected with the prosperous sugar industry. While scant physical traces of Whitechapel’s sugarhouses remain, drawings and descriptions from the archives reveal the diverse buildings associated with this industrious community. Following a newly-arrived German sugar baker, a well-established sugarhouse owner, and a school mistress, this talk will explore what everyday life was like in Whitechapel’s oft-forgotten Deutsche Kolonie.

Sarah Milne is a research associate and website co-editor on the Survey of London’s Whitechapel project. She is particularly interested in how global exchanges have shaped London’s built environment through the centuries. Sarah is also a lecturer in the history of architecture at the University of Westminster.

Mapping and Place

Seif El Rashidi, Shlomit Flint, Duncan Hay, Laura Vaughan

The Survey of London’s ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ interactive map will be a starting point for thoughts from and discussion by a panel with a range of expert engagements with urban geography – GIS systems, participative and otherwise, micro-geography, psychogeography and space syntax.

Seif El Rashidi is the project manager for Layers of London, based at the Institute for Historical Research. Layers of London is creating a website bringing together a significant collection of historic maps and other London-related resources for the first time, working with community groups, schools and the general public to encourage them to contribute information about the London that they know.

Shlomit Flint is an architect with a master’s in public policy and planning and a PhD in geosimulation and spatial analysis. Shlomit has studied the impact of recent immigration on Whitechapel’s built environment through digital means with a desire to influence public policy. She is a Research Fellow with the Survey of London’s Histories of Whitechapel project.

Duncan Hay is a Research Associate at the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis at UCL with expertise in psychogeography and English literature. He has been responsible for the design and functioning of the website for the Survey of London’s ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ project.

Professor Laura Vaughan is Director of the Space Syntax Laboratory at UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture. Her most recent publications include a study of the significance of urban space in shaping religious solidarities in nineteenth-century Whitechapel, while her book on the spatial dimensions of social cartography, Mapping Society, has been released this autumn with UCL Press. Laura is a member of the Survey of London’s Whitechapel project’s steering group and advisory panel.

The Petticoat Lane Foxtrot

Alan Dein

From singers, songwriters, conductors, and cantors to musicians, managers, proprietors of record shops and club owners – Alan Dein reflects on the stories of Whitechapel’s Jewish community whose musical roots go back to the major wave of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants fleeing the pogroms in Eastern Europe at the end of the nineteenth century. Their stories are entwined with the development of the British recorded music industry. In particular, Dein focuses on the remarkable sounds of Cockney Jewish-themed jazz recorded in London between the 1920s and the 1950s. As many of the tunes celebrate Jewish cuisine – from beigels to schmaltz herrings – Dein will also reflect on the world of speciality food shops and businesses that proliferated in Whitechapel during the interwar years.

Alan Dein is an oral historian and radio broadcaster. He has presented documentary features for BBC Radio for over twenty years, and has worked on oral-history projects and podcasts for numerous institutions including The British Library, The Museum of London, The Royal Parks, English Heritage, The Guardian, The Jewish Museum, and local history and community groups. He was the project co-ordinator of ‘King’s Cross Voices’ (2004–2008), a major Heritage Lottery Funded oral history project exploring the living memory of London’s King’s Cross. In 2012, Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives published After You’ve Gone – East End Shopfronts, 1988 which accompanied an exhibition of his photographs.

Sailors and Settlement

Kinsi Abdulleh, Tamsin Bookey, Derek Morris

The proximity of the Thames and London’s port to southern parts of Whitechapel, including Wellclose Square, Dock Street and Ensign Street, has meant strong connections with mariners and other seafaring people from several regions of the world since at least the eighteenth century. Their impact on the built environment has ranged from sailors’ homes or hostels to more enduring settlement and descendants.

Tamsin Bookey is the Heritage Manager at Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives, an archivist and a member of the Survey of London’s Whitechapel project’s steering group and advisory panel.

Derek Morris MSc, FGS, is a graduate of Queen Mary College, University of London. He found that his ancestral family lived in Mile End in 1770 opposite Captain James Cook, the famous explorer, and this discovery led him to extensive research on eighteenth-century Stepney. He has written four books on the social history of the area, including Whitechapel 1600–1800: A social history of an early modern London Inner Suburb and London’s Sailortown 1600–1800: A Social History of Shadwell and Ratcliff, an Early Modern London Riverside Suburb (with Ken Cozens), both published by the East London History Society. He is also an associate member of the University of Portsmouth, Port Towns & Urban Cultures Project.

Kinsi Abdulleh is a visual artist, a social activist and the founder of NUMBI Arts.

View from the roof of Mosque Tower, Whitechapel Road, 2016, photograph by Rehan Jamil for the Survey of London

Bengalis in London’s East End

Julie Begum

This presentation will trace the history of the Bengali community in the East End since the seventeenth century, looking at early settlers and more recent post-war Bengali migration history, characteristics and differences, relationship to Empire, and social dynamics.

Julie Begum is Co-founder and Chair of the Swadhinata Trust (www.swadhinata.org.uk) and the recipient of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets Civic Award for Outstanding Service to the Community 2017.

Heritage and Community

Emily Gee, Hudda Khaireh, Will Palin, Howard Spencer

This discussion will address Whitechapel’s histories in relation to conservation (current and past), loss, memorialisation, sites of memory and questions of identity and authenticity in relation to heritage and its definitions.

Emily Gee is Historic England’s London Planning Director. She has worked at Historic England since 2001 and served as Head of Listing Advice from 2011 to 2016. Emily also leads Historic England’s Twentieth Century Network. She has published on Victorian and Edwardian housing for working women and on listing, including post-war buildings and issues of diversity. Emily is a member of the Survey of London’s Whitechapel project’s steering group and advisory panel.

Hudda Khaireh is an independent researcher with a background in Public International Law and a member of Thick/er Black Lines artist collective.

Will Palin is the Director of Conservation at the Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich, and a former Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage. He is also a founder of the East End Preservation Society.

Howard Spencer is a senior historian with English Heritage with responsibility for London’s blue plaques scheme. He is the editor of The English Heritage Guide to London’s Blue Plaques.

Mapping workshop at London Enterprise Academy, 2017

Hido Raac: Place-making and Demarcating

Hudda Khaireh

History is the fruits of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.

– Historian Professor Michel-Rolph Trouillot

Hido Raac is a waking Odyssey, exploring the sites and histories of the Somali community in East London to open discussions on how communities and geographies are formed as well as the events, institutions and ideologies that shape our understanding or ‘mapping’ of an area. Hudda’s contribution to the Whitechapel History Fest will be to share her experiences of the Hido Raac project – particularly the sites identified and community stories connected to Whitechapel.

Hudda Khaireh is an independent researcher with a background in Public International Law and a member of Thick/er Black Lines artist collective.

Histories from the Archives

Malcolm Barr-Hamilton, Dor Duncan, Jamil Sherif

Archives, whether formally constituted and public, or more contingent in nature, are an essential source for understanding the historic built environment and the people that shape it, perhaps all the more so in an area like Whitechapel that has seen so many changes. This discussion with examples from the Tower Hamlets Archives, the newly opened archive at the East London Mosque and others will foreground different ways archives can enhance awareness of local and wider histories and multiple voices.

Malcolm Barr-Hamilton has long been the Borough Archivist for the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

Dor Duncan is an artist and archivist at Whitechapel Gallery.

Jamil Sherif is part of the Research and Documentation group at the Muslim Council of Britian, and the Chair of the East London Mosque Archives Steering Group. He has set up the first formal archive of a Muslim organisation in the UK, now situated in the East London Mosque and publicly accessible. His biography of Abdullah Yusuf Ali, the most widely read English translator of the Quran, Searching for Solace was published in 1994 and he continues to research and write on the key figures of British Muslim history.

‘Whitechapel Boys’: The view from Whitechapel across one hundred years

Chris Searle and Ron McCormick

In April 2018, the writer Chris Searle and photographer Ron McCormick published a re-appraisal of the poetry of the World War One poet Isaac Rosenberg to mark the centenary of his death in the French trenches at the end of the great conflict. The book tells the story of Rosenberg’s early development as an English artist in the first two decades of the twentieth century and is controversially illustrated with McCormick’s photographs of Spitalfields and Whitechapel taken during the 1970s when the area was undergoing a rapid change from a community of predominantly émigré Jews and facing a new influx of immigrants from the Indian sub-continent. Searle explores these cultural and political influences in his text and develops a thesis about the development and value of Rosenberg’s poetry for a modern society. While the changing culture of the vibrant multi-ethnic district of East London of modern times echoes the experiences and earlier world of Rosenberg and his fellow Whitechapel Boys sixty years before. The whole is underpinned with a powerful visual picture of Whitechapel as it might have appeared in the 1920s mirrored through McCormick’s photographs as a record of a similar patchwork of family and tenement living, street life, poverty and industry, told through the faces of Whitechapel people in the 1970s. In many ways Searle and McCormick’s partnership and their engagement in the life and culture of East London reflect the creative endeavours and experiences of their earlier forebears, the ‘Whitechapel Boys’.

Chris Searle has written or edited over fifty books on subjects as diverse as education, poetry, language, journalism, cricket and jazz. Among them The Forsaken Lover (which won the Martin Luther King Award in 1973), Classrooms of Resistance, The World in a Classroom, Words Unchained: Language and Revolution in Grenada, Your Daily Dose: Racism and ‘The Sun’, Pitch of Life and Forward Groove. He writes a weekly jazz column for the socialist daily newspaper, the Morning Star. In 1971 he collaborated with Ron McCormick to produce the influential book of schoolkids poetry, Stepney Words, and a number of other projects in East London, most recently Stepney Words III (commissioned by Rich Mix, the Shoreditch media arts centre). Together they produced and published Whitechapel Boy, a reappraisal of the poetry of the First World War poet, Isaac Rosenberg, to commemorate the centenary of the poet’s death in the French trenches in April 1918.

Ron McCormick’s photographs, ‘Neighbours – Spitalfields to Whitechapel’ were exhibited at Whitechapel Art Gallery and The Serpentine Gallery. He was a commissioned artist for the seminal exhibition ‘Inside Whitechapel’ (Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1973). With a background in both fine art and documentary photography, he has been involved in social and community initiatives since the early 1970s. He taught at the prestigious School of Documentary Photography in Newport, South Wales, and Southampton Solent University where he established the university art collection and became its first curator (2001–14). He is represented in the collections of the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, The National Library of Wales, The Arts Council of Great Britain, The Crafts Council, Contemporary Arts Society for Wales, Fotogallery Wales, and Curtin University, Perth, Australia.

George Holland: Whitechapel’s Unsung Hero

David Charnick

From the 1850s until his death in 1900, merchant-turned-evangelist George Holland worked to help relieve the distress caused by poverty in the Whitechapel area. Despite his considerable efforts, he is almost unknown today; this presentation will show why he deserves to be better known.

David Charnick is a City of London guide who also guides extensively in Tower Hamlets. Additionally he teaches tour guiding courses through the borough’s Idea Store Learning adult education service. He is the author of The Dark Side of East London, which considers life in the East End in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Stories from my time at the London Hospital

Jil Cove

Jil Cove looks back over fifty years in Whitechapel, from her early days as a student midwife at the London Hospital to her life now in Old Castle Street.

Jil Cove came to work at the London Hospital in 1961. She fell in love with the area and has stayed ever since.

The Co-operative Wholesale Society’s buildings in Whitechapel

Rebecca Preston

The Co-operative Wholesale Society was headquartered on Leman Street and Prescot Street from 1881. Its significance in the area’s history is represented by some impressive buildings, now converted to other uses.

Rebecca Preston is based at Royal Holloway, University of London, and also teaches at the Institute of Historical Research. She is currently engaged as a researcher/writer for the Survey of London’s work on Whitechapel. She has recently been a research associate on another AHRC-funded project, ‘Pets and Family Life in England and Wales, 1837–1939’. Her research spans the history of urban and suburban development, including parks and gardens and different kinds of living space in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Britain, and she has a particular interest in the relationship of people to place.

Exploring Wilton’s Music Hall and its history

Carole Zeidman

Carole will talk about Wilton’s in the context of Whitechapel, the factors for the building’s exceptional survival, and its continuing fascination today.

Carole Zeidman is an ‘Old East Ender’, who lived in Cable Street as a young child in the 1950s and was Wilton’s Historian and Senior Tour Guide from March 2011 to December 2017.

East End Vernacular: The artists who painted the East End streets in the 20th century

The Gentle Author

The Gentle Author will speak about a subject that he published in book form in 2017.

The Gentle Author has been publishing a daily story about the culture of the East End on the Spitalfields Life blog for the past nine years and is the author of a number of books including Spitalfields Life, The Gentle Author’s London Album, The Cries of London and East End Vernacular.

Graces Alley with the entrance to Wilton’s Music Hall in 2018, photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Saturday 27th October – 10am–4.45pm

Life in the East End

Imam Ajmal Masroor

Ajmal Masroor will speak about Whitechapel as he knows it and knew it from childhood. He will tell some stories around photographs that represent his own memories and experiences.

Ajmal Masroor is a renowned broadcaster, commentator and Imam with his roots in the East End. In 2014 he was recognised in the Muslim 500 as one of the most influential Muslims in the world today. He has presented programmes on BBC One, Channel 4, Islam Channel and Channel S. He writes regularly on socio-political and spiritual issues facing the world in general but the Muslim community in particular. His writing has been published by Emel, the New Statesman, The Guardian and the Evening Standard. He leads Friday prayers at four mosques in London: Goodge Street, Palmers Green, West Ealing and Wightman Road in Haringey. He studied Islam, politics, Arabic language and relationship counselling. He holds an MA from Birkbeck College, University of London.

Survival and Traces: Whitechapel’s pre-Victorian buildings

Peter Guillery

Development pressure is not a new phenomenon in Whitechapel. Waves of investment and improvement across centuries have displaced most of early Whitechapel’s buildings, in many cases genuinely for the better. There are a few notable survivals, of fabric if not of function, as at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, St George’s German Lutheran Church, and the former Davenant School. Other sites exhibit more partial, even hidden traces of medieval, early-modern and Georgian Whitechapel, examples such as Altab Ali Park and Wellclose Square.

Peter Guillery is an architectural historian and editor for the Survey of London, where he is the Principal Investigator for the AHRC-funded ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ project. Away from the Survey, his publications include The Small House in Eighteenth-Century London, and, as editor, Built from Below: British Architecture and the Vernacular and Mobilising Housing Histories: Learning from London’s Past (with David Kroll).

Sharing Local History

Celeste, Gary Hutton, Danny McLaughlin

This session will be focussed on the experiences of three local residents, who all know and love Whitechapel, but who have different stories of place to tell. It is a forum to reflect on the diverse ways in which they have gathered and shared local history within the community, and what motivates them to do so. The discussion will consider the use of digital and social-media platforms as well as oral history and photography.

Celeste is a teacher and performance artist based in Shoreditch. Celeste presents new works exploring themes of time, place and identity in London.

Gary Hutton comes from a very colourful background, having spent his life growing up in Whitechapel. Gary’s Whitechapel is a very different place, and with a different view, from many, as the social history of Whitechapel is runnning through his veins. Gary will talk about the Whitechapel he loves and around which he guides the occasional walking tour to provide a different view of Whitechapel. In his spare time, Gary helps run two sites on social media, one being the Facebook group ‘Whitechapel Born n Bred’ and he is also the founder and chief executive of the charity Product of a Postcode.

Danny McLaughlin was born in, and has lived his whole life in Whitechapel. Though his work takes him worldwide investigating fraud, he is always happiest at home in E1.

The former Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Road, 2016, photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The expansion and remodelling of the London Hospital, 1884–1919

Amy Smith

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the London Hospital was one of the largest general hospitals in the country. Approximately 800 beds for more than twenty-one types of patients, all treated for free, were arranged across an extensive historic building that had gradually become outdated. This talk explores the remodelling and enlargement of the hospital between 1884 and 1919 to form a sprawling medical complex that functioned on modern lines. A century later, much of that complex has been demolished and altered as part of the hospital’s transferral to a new tower block.

Amy Smith works as an historian on the Survey of London. She has recently researched the Royal London Hospital for the current study of Whitechapel and is now working on a forthcoming volume on Oxford Street.

Sugarhouses and German Refiners

Andrew Byrne, Sigrid Werner

Sugar refining, widespread in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Whitechapel, was very largely managed by German immigrants. Andrew will talk about sugar-baking or sugar-refining houses, their impact on the East End, their architects and their demise. Sigrid will talk about the development of the German immigrant community in the East End, its churches, schools and synagogues and its destruction in World War One.

Andrew Byrne is an architectural historian. He ran the Spitalfields Trust in the 1990s and is the founder of LONDON 1840, which is building a scale model of London as it was in that year.

Sigrid Werner has been a resident of Tower Hamlets for almost twenty years and of London for over thirty years. She is a theologian by training and a local historian for the East End. She specialises in the history of the German community in Tower Hamlets, was one of the authors of the 250th anniversary exhibition at St George’s German Lutheran Church in Alie Street, and has also published on Islington and Tower Hamlets church history and local family history. She works locally with an education charity.

Citizens of No Mean City: Toynbee Hall, Whitechapel Gallery and the Survey of London

Aileen Reid

In 1873 an idealistic young clergyman and his wife arrived in ‘the worst parish in London’, keen to make a difference. By the end of the century they had created Toynbee Hall and were building Whitechapel Gallery, and had nurtured the young C. R. Ashbee, who founded the Survey of London in the 1890s. This talk will explore the common and sometimes problematic origins of these now rather disparate enterprises.

Aileen Reid has been a research associate on the Survey of London since 2005, currently working on Whitechapel’s historic core around the High Street, and as web co-editor of the Whitechapel Histories project. Her interests focus on the long nineteenth century, from the ‘art architects’ (monographs on E. W. Godwin and a group of C. F. A. Voysey townhouses will be published in 2020) to housing reform, and the use of film as a research tool in architectural history.

East End Rebels 1880s to 1930s

David Rosenberg

In the struggle for better lives in the East End, sweatshop workers downed tools, bakers formed workers’ cooperatives, women organised rent strikes, councillors went to prison, people built barricades, and police were pelted with kitchen implements. In this talk you will discover who was agitating, rioting and refusing to accept injustice and inequality and what they achieved.

David Rosenberg is a writer, educator and tour guide who focuses on London’s radical history. He is the author of Rebel Footprints and Battle for the East End and has a website at www.eastendwalks.com.

Film premiere: ‘Changing Tastes; Whitechapel’s south Asian restaurants’

Nurull Islam and Rehan Jamil

The premiere of a short film commissioned by the Survey of London on the south Asian restaurant scene in Whitechapel. It can be argued that the palate is one of the best barometers of social change, and Whitechapel’s history can certainly be tracked through its menus and restaurants. This film captures one strand of this history, looking at how Bangladeshi and Pakistani migrants established both themselves and a new cuisine in Whitechapel, how this has evolved and where it is going. Interviews and new footage provide a fascinating insight into a vibrant and important aspect of Whitechapel’s story.

Nurull Islam is Centre Director for the Mile End Community Project.

Rehan Jamil is a documentary photographer who is primarily concerned with communities in transition. Rehan completed a long-term personal project ‘The East End of Islam’ (1997–2007) a photographic documentary relating to the Muslim community in Tower Hamlets and around the East London Mosque. Rehan’s photographs have been exhibited in many galleries and museums including the Whitechapel Gallery, the Station Gallery Frankfurt, Ragged School Museum, Bruce Castle Museum, the Menier Gallery and St Ethelburga’s Centre for Reconciliation and Peace. Rehan is the author of several books including Common Ground: Portraits of Tower Hamlets, Ocean Views, Common Ground: Aspects of Contemporary British Muslim Experience and Peace by Piece.

The Jagonari Centre and the East London Mosque: Architecture in the 1980s

Shahed Saleem

The 1980s saw the completion of two major landmarks for the local community in Whitechapel. This talk will trace the trajectory of these projects, how they started, developed, and the struggles that they endured and overcame. The architectural process that led to the buildings that stand today, one a place of worship and the other a community facility, will also be described, drawing on the material that has been gathered through the Survey’s research project.

Shahed Saleem is a Senior Research Fellow at the Survey of London, a practicing architect, and a design studio tutor at the University of Westminster School of Architecture. His particular research interests are in the architecture of migrant and post-migrant communities, and in particular their relationship to notions of heritage, belonging and nationhood. He has authored The British Mosque, an architectural and social history, published by Historic England.

The former Jagonari Women’s Centre, Whitechapel Road, 2017, photograph by Shahed Saleem for the Survey of London

The Survey of London’s ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ Project Reviewed

Open discussion led by Peter Guillery

This session is intended as a general discussion, to sum up the Whitechapel History Fest and to reflect on the Survey of London’s website-based work in Whitechapel.

Whitechapel: An Historical Overview

Dan Cruickshank

Dan Cruickshank will draw on deep familiarity with and knowledge of Whitechapel and its buildings, looking back to sum up proceedings with an account of works carried out by the Spitalfields Trust in Whitechapel.

Dan Cruickshank is an architectural historian, a television presenter and the author of numerous books, including Spitalfields: The History of a Nation in a Handful of Streets. As a long-standing resident of E1 he knows Whitechapel well.

Tower House (former Rowton House), 81 Fieldgate Street, Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 28 September 2018

With its distinctive roofline and seven storeys rising sixty feet, Tower House is a local landmark that did indeed tower above its neighbours when first built. Initially called Rowton House, Whitechapel, the building opened in 1902 and was the fifth of six ‘Rowton Houses’ established in London between 1892 and 1905 to provide decent, low-cost accommodation for single working men. Known as Tower House from 1961, during the late 1970s the building was found to be inadequate as housing and began to decline. After various schemes to adapt it for use as a public building and supported housing fell through, Tower House was sold to a developer and converted to upmarket apartments in 2005–8.

Tower House, Fieldgate Street, view from the southwest in 2016. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Rowton Houses were large model lodging houses founded by Montagu (‘Monty’) Lowry Corry, later Lord Rowton (1838–1903), Tory politician, nephew of the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, and former secretary to the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. Rowton was appointed Chairman, the other founding directors being Cecil Ashley, Richard Farrant and Walter Long, MP and former Chairman of the Local Government Board; after accepting a Cabinet post, Long was replaced by William Morris (junior), a partner in the firm of Ashurst Morris Crisp, which acted as the company’s solicitors.

Rowton House, Whitechapel from the east, c.1903. (From Jack London, The People of the Abyss, 1903)

Known as ‘hotels for working men’, the buildings were a response to the capital’s housing crisis of the 1880s, intended as superior alternatives to the common lodging house, where the poorest Londoners slept in dormitories over a shared kitchen. Like other kinds of model housing, Rowton Houses were intended to be models of hygiene and order, and as models for other organisations to follow. Rather than being purely charitable institutions, they were designed to turn a modest profit for shareholders, on the model of five per cent or ‘remunerative’ philanthropy. The local and national press, and medical, architectural, sanitary, and municipal journals were broadly supportive of the Houses’ improving aims and reported on them at length.

Rowton Houses were not intended to be the cheapest lodgings. Common lodging houses cost from around 4d per night in London at this time and the London County Council (LCC) initially charged 5d at its municipal lodging house. Rowton Houses insisted that their enterprises were not charitable or philanthropic organisations but poor men’s clubs or hotels. At the opening of the Whitechapel House, the chairman, Richard Farrant, was reported as saying privately that ‘the Carlton and Reform Clubs might have superior upholstery but that there was not a club in London where a man could live so comfortably, economically, and healthily as at the Rowton Houses’. [1] The press made frequent approving comparisons with gentlemen’s clubs and, in many ways, including the exclusion of women, the suites of dayrooms and the encouragement of male sociability, Rowton Houses did resemble all-male elite clubs.

The first Rowton House opened at Vauxhall in 1892 (470 cubicles). King’s Cross opened in 1896 (677), Newington Butts in 1897 (805), Hammersmith in 1899 (800), Whitechapel in 1902 (816) and Camden Town (Arlington House) in 1905 (1,087). The architect for all apart from Vauxhall was Harry Bell Measures, whose characteristic red-brick blocks lined with slit windows, leavened with gables, turrets and terracotta detailing, created a new and easily recognisable style of building in the capital. Of the five London Rowton Houses designed by Measures, only Tower House and Arlington House survive and only Arlington remains in use as a hostel.

The Whitechapel building was made up of two adjoining parallelograms separated by an inner courtyard open at one end, in order to provide good air circulation and light. On concrete-clad steel construction, the elevations are in pressed Leicester facing bricks, with Fletton bricks on inward faces. Semi-circular windows face outwards from the dayrooms on the first two floors, including in the two bays at this level (one of which has been replaced by a new entrance), and above these are the rows of narrow windows to the hundreds of cubicles, the sashes and frames to which have been replaced throughout the building. Externally, the expanse of brick is relieved with gables, turrets and pink terracotta dressings, and the large projecting porch, flanked with octagonal finials, and which served as the original entrance, is also of terracotta. The diminutive cherub presently seated on the central finial is a recent addition; it replaced a larger figure of a child holding a globe on his shoulders, which may have represented a young Atlas.

Original entrance porch at Tower House, 2016. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

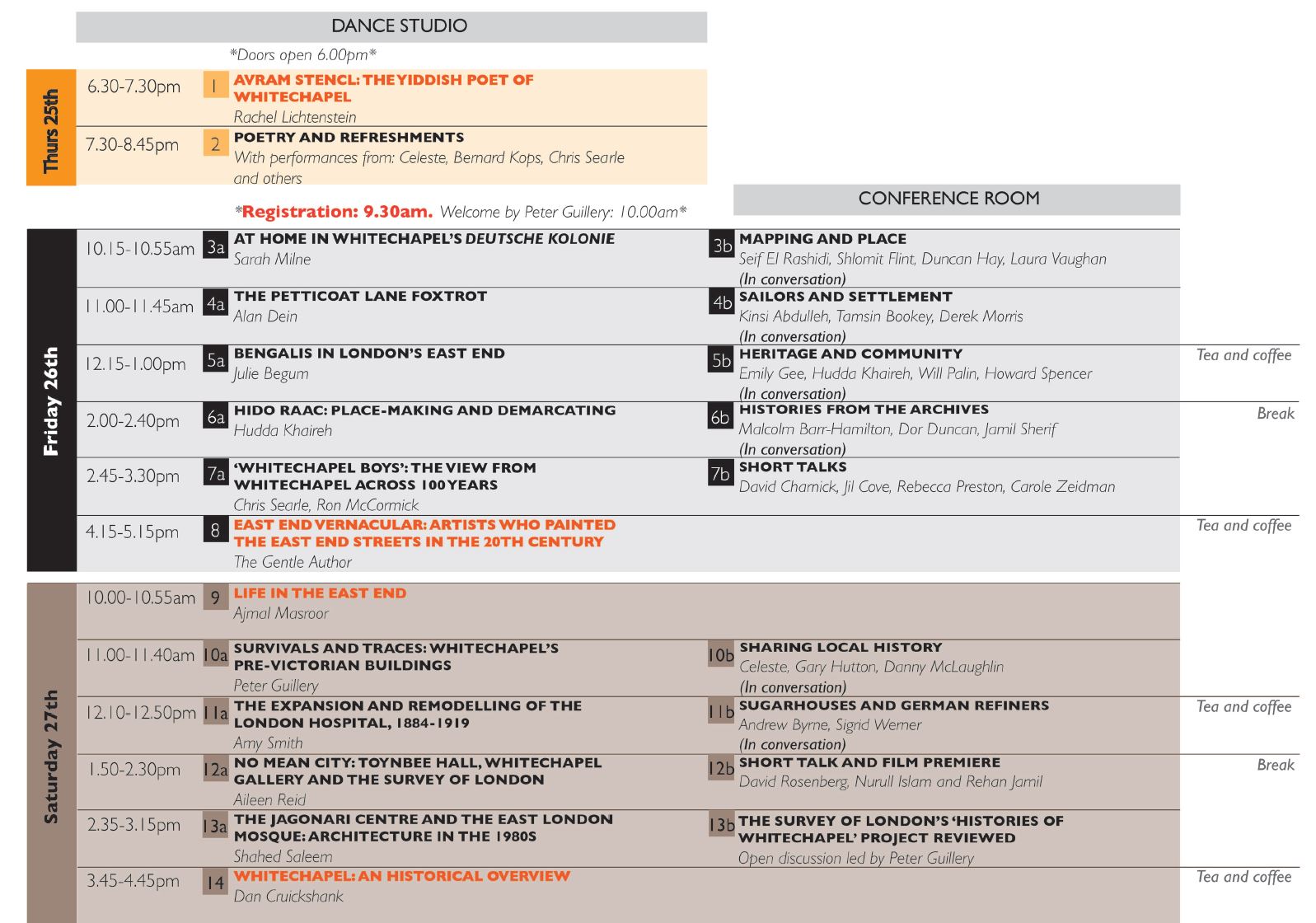

Originally the first two floors (known as the ‘entrance floor’ and, above that, the ‘ground floor’) contained the office, staff quarters, and the lodgers’ kitchen, dining and other dayrooms, washing facilities, lockers and services; above these were five floors of cubicles, whose rows of narrow windows contributed to the building’s outwardly institutional appearance. When Measures was asked why he didn’t group his windows, he replied that ‘if I yield to that temptation, then the sleeper has to pay the penalty for the sake of my elevation. Personally, I think the sleeper comes first and that my elevations should truthfully proclaim it’. [2] Despite the new entrance and alterations to the windows made as part of the 2005–8 conversion, the Fieldgate Street elevation still reads as a Rowton House, the major alterations to the exterior being the penthouse floor and at the rear of the building.

On entering Rowton House, Whitechapel, lodgers bought a ticket at the office window and, if they wished, weekly lodgers could pay a 6d deposit for a locker, before passing through a turnstile and into a vestibule. From here, lodgers could go up a flight of stairs to a small ‘glass-roofed lounge with palms and flowers’. [3] Or they could enter the main corridor, on the lower ground ‘entrance floor’, which ran east–west through the building. The lockers, and the sinks, baths and footbaths (free), baths (1d including soap and towel) and facilities for washing and drying clothes, were all located on the east side of this floor. The tailor, shoemender and barber were in the same area. Once clean and dressed, the men could go to their cubicle for the night or make use of the dining and recreation rooms up to a certain time in the evening.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, plan of the entrance floor, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California) Please click on the image to view a larger version.

A huge dining room occupied the centre of the entrance floor, with seating at teak tables for 456 men. Lodgers could cook their own suppers over a range, either with food they brought with them or from ingredients bought at the shop. Alternatively, they could buy a cooked meal at prices which, as the company stressed, amounted to little above cost, achieved through the bulk buying of provisions. Lodgers could purchase a pint of tea in a special Rowton House-emblazoned mug for a penny in 1906, while 5d bought a plate of roast mutton or beef with seasonal vegetables followed by a hot pudding. Top-lit and ventilated with lantern lights, the dining room was finished with the same ‘high dado of glazed brickwork in tints of cream and chocolate’, as found throughout the dayrooms. [4] Due to the size and function of the building, institutional associations were impossible to escape but the aim was to mitigate this through dayroom arrangements and decoration and, at Fieldgate Street, to ‘give an effect of sprightliness and comfort’. [5] Framed pictures hung on the walls, the plastering ‘tinted to a shade of terracotta’ above the tiling.[6] While Measures was responsible for the design of the building, Rowton and Farrant personally oversaw the interior design and decoration, choosing the bedding, furniture, pictures and, even, at King’s Cross, a stag’s head shot by Rowton, for the walls.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, dining room, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California)

On the south side of the corridor on the entrance floor lay the smaller smoking room, its windows in the central bays looking, through the railings, into Fieldgate Street. This had space for 140 lodgers at teak tables with additional easy chairs around the fire places at each end. Cards and games of chance which might encourage gambling were banned but chess and draughts were provided.

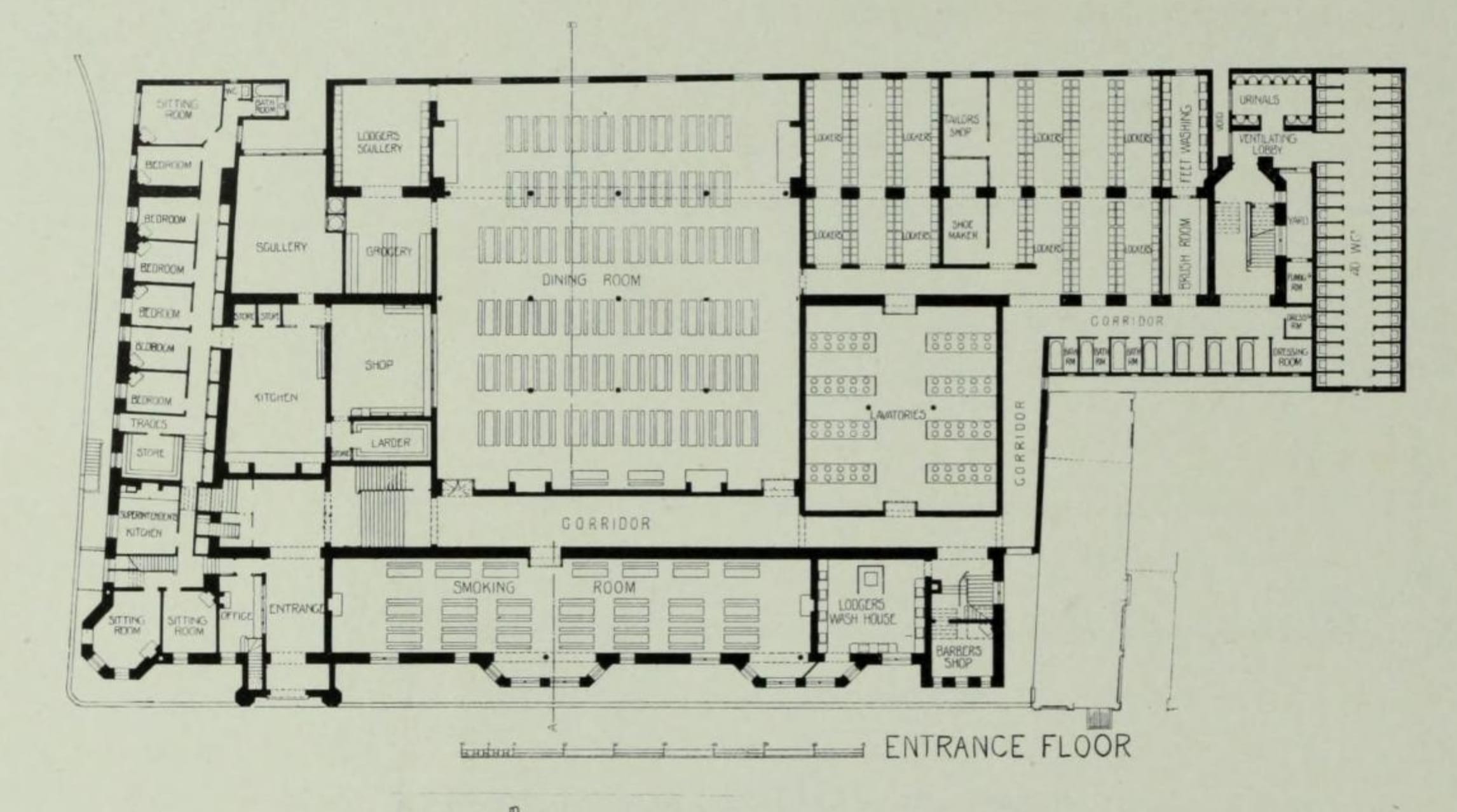

The reading room lay immediately above the smoking room on what was known as the (upper) ground floor. This was fitted with cupboards for newspapers and bookcases, from which lodgers could borrow books on application to the Superintendent, open bookcases having been abandoned across the Houses after thefts made it necessary to lock them.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, plan of the ‘ground’ (first) floor, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California) Please click on the image to view a larger version.

A series of panels ‘emblematic of “the Seasons”’ hung in the reading room. These took up a large part of the back wall facing the windows onto Fieldgate Street, fitted above the tiling. As was widely reported, these were ‘painted by Mr H. F. Strachey of Clutton, near Bristol, a cousin of Lytton Strachey and art critic of The Spectator. They were given by him as the practical interest of an artist in the elevating work of a Rowton House’. [7] ‘Each season is represented by a single figure and also by a larger composition, while over the fireplace in the middle is a small allegorical work. In it a symbolical figure of England sits enthroned, while the fruits of the land are brought to her by the cultivators’. [8]

There were no panels in the other Rowton Houses and it is not known what happened to those at Fieldgate Street. It is possible that they were lost during alterations of 1953, which divided the Reading Room into a Billiard Room and a Quiet Room.

Near the reading room was a door to the open-air or smoking lounge. As at the previous Rowton Houses, this was formed on the roofs of the rooms below, in this case the kitchen, dining and washroom areas. Invisible from the street, this space, in the void which allowed air and light to circulate within the building, was fifty feet wide and surrounded on three sides by the cubicle floors. Benches were placed around the lantern lights and it was laid out with tubs of flowers as a roof garden. Like the decoration, pictures and pot plants within the House, the garden was an attempt to de-institutionalise the buildings.

Rowton Houses prided themselves on the superior size and construction of their cubicles and on the quality of the beds and bedding. After experiments with shared dormitories at Vauxhall proved unpopular, all subsequent Houses were provided with individual sleeping cubicles. These measured 5ft by 7ft 6inches and were 9ft high. Each lodger had a sash window under his own control, an iron bedstead with a sprung mattress, a clothes hook, and a chair. The partitions (of strong pine, rather than iron as in shelters and some model lodging houses) reached nearly to the ceiling, with a space at the top. Initially this was left open but in the early twentieth century was meshed in after ‘fishing’ by residents into neighbouring cubicles showed that valuables were unsafe. By this means visual privacy was achieved while ensuring the building remained light and well ventilated.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, footbaths, a cubicle and corridor, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California) Please click on the image to view a larger version.

This account is extracted from a fuller history by Dr Rebecca Preston for the Survey of London (link). That draws on the project, At Home in the Institution? Asylum, School and Lodging House Interiors in London and South-East England, 1845–1914, led by Jane Hamlett at Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2010–11, and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (RES-061-25-0389).

[1] Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6.

[2] British Architect, 22 March 1901, p.213.

[3] Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6.

[4] East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p. 8

[5] London Evening Standard, 7 August 1902, p.7.

[6] East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p.8.

The French Chapel in Marylebone

By the Survey of London, on 7 September 2018

A reminder of the once notable French presence in Marylebone is the French definite article in the name. The old name was Marybone, a corruption of Maryborne, referring to the church of St Mary by the bourne built in the early 1400s. Although ‘Mary le Bone’ and variants were in widespread use throughout the eighteenth century, Marybone was still the most common name until the early nineteenth century, when it began to fall out of use, (St) Marylebone subsequently becoming the invariable form. But even today, there are alternative pronunciations, essentially English and French.

There was a French church off the High Street by 1709, perhaps earlier, and from the late seventeenth century French émigrés ran a well-known school near by, patronized by the nobility as a prep school for Westminster and Eton. The French population then was Protestant, part of the Huguenot diaspora particularly associated in London with Spitalfields. But a century after Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes, prompting the main Huguenot exodus, the Revolution brought a new wave of French refugees to Britain, this time Roman Catholic and royalist, many of them priests, many of them aristocrats. A large number settled at least temporarily in the fashionable and still-developing district of south Marylebone, where the executed Louis XVI’s younger brother the Comte d’Artois (from 1824 to 1830 Charles X of France) held court in Baker Street. Consequently, Marylebone became a vital counter-revolutionary centre and it is likely that this association with France helped to bring about the dominance of the French-sounding form of the place name.

The French Chapel in 1890. Watercolour by Thomas G. Appleton. (© Westminster City Archives)

One of thousands to flee to Britain was the Bishop of St Pol-de-Léon, Jean François de La Marche (1729–1806), who landed in Cornwall from a smuggler’s boat in 1792. As the effective leader of the exiled French clergy, working with the Vicar Apostolic of London, Bishop John Douglass, de La Marche was behind the opening of several French chapels including that in Marylebone. There was already a Roman Catholic chapel there, recently opened in association with the Spanish embassy in Manchester Square, the forerunner of present-day St James’s, Spanish Place. But a makeshift French chapel was soon set up in Paddington Street, in a house on the corner of Dorset Mews East (now Kenrick Place), under the charge of the Abbé François Bourret of the Society of Saint-Sulpice.

Extract from the Ordnance Survey 25-inch map, 1875, showing the French Chapel in Little George Street, just south of King Street. (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

In 1798 the site for a permanent chapel was found on the Portman estate in Little George Street, a now-vanished mews just east of Gloucester Place between King Street (part now of Blandford Street) and George Street. The street was as yet only half built up. Funds for building came from French exiles and English sympathizers, Protestant as well as Catholic, including the Marchioness of Buckingham who had converted to Catholicism in 1788. A substantial grant came from the Montreal branch of the Society of Saint-Sulpice. Much of the physical work was carried out by priests and their compatriots. Dedicated to Our Lady of the Annunciation, the chapel opened on 15 March 1799 with a grand service of consecration attended by French royalty and senior ecclesiastics. Over the following decades, the chapel saw many important services, attended by many of the leading members of the royal houses of Bourbon and Orléans.

Front elevation, 1886, by Henry Petit, architect. (© Portman Estate)

In its original form, the chapel was exceptionally modest, externally plain and comprising a narrow space with a single aisle. In 1815, following the restoration of the monarchy, Louis XVIII formally granted it the status of Chapel Royal and a grant sufficiently large to allow pew-rents to be abolished. This led to the attendance of many poor Catholics, Irish and English as well as French, and the chapel had to be enlarged, resulting in a second aisle, gallery, and additional accommodation. Financial support from France stopped with the revolution of July 1830, but was later reinstated, finally ending under the Third Republic in 1881. Thereafter the chapel depended, as originally, on voluntary subscriptions and became effectively a private chapel. A fund-raising campaign for repairs and a new lease from the Portman Estate was set up under the leadership of Cardinal Manning, who rededicated the chapel to St Louis de France. Improvements to the building in 1886 were overseen by the architect Henry Petit of Welbeck Street (1847–1926), whose Paris-born parents had eventually settled in Marylebone. But when the new lease was obtained it was for only 25 years.

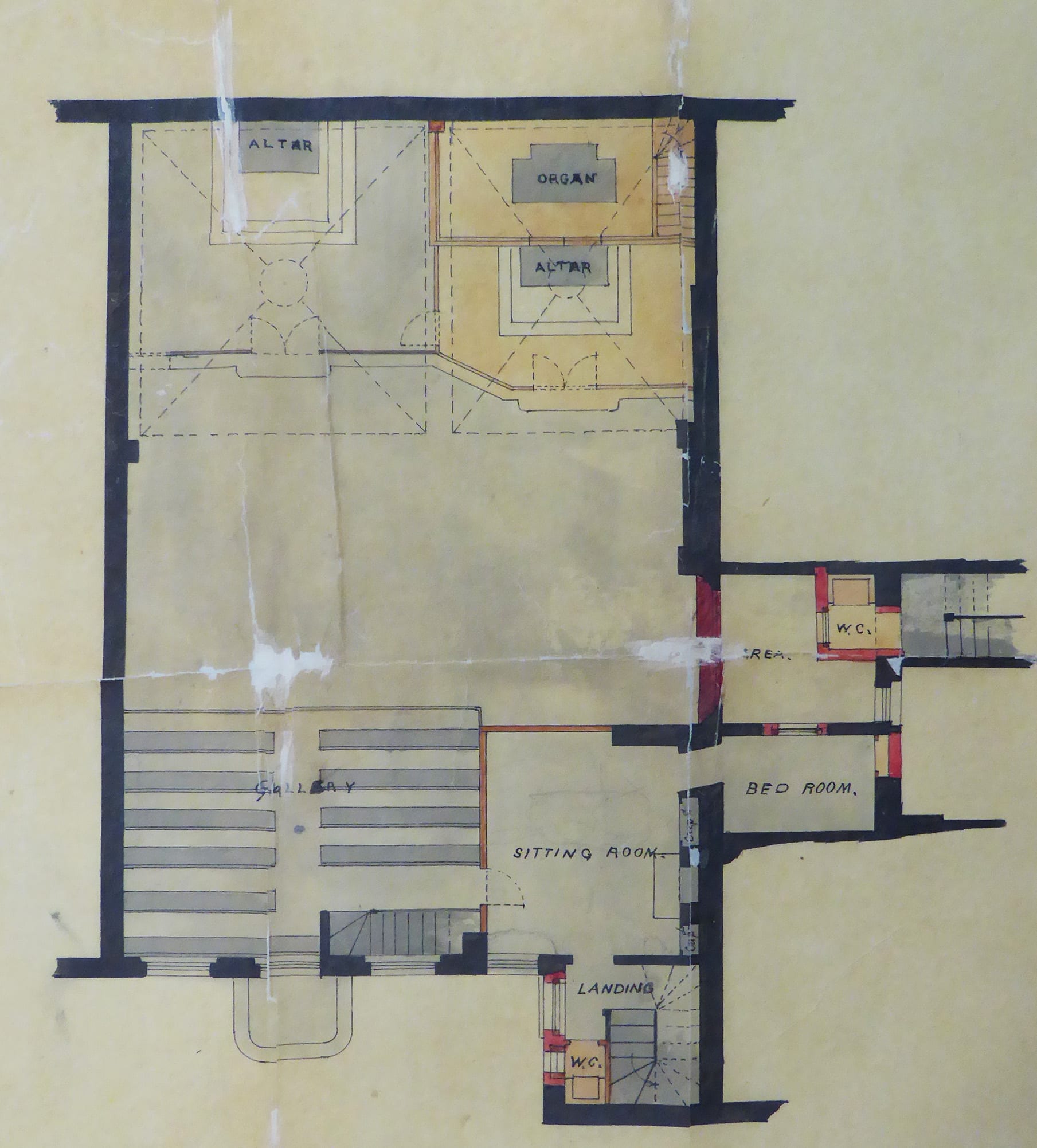

Ground plan, 1886, by Henry Petit, architect. (© Portman Estate)

As described in 1886, the interior of the chapel was ‘scarcely larger than an ordinary drawing room’, with the main altar and ‘a diminutive stand for an American organ’ at the far end, facing the gallery, which was at one time set aside for royalty. There were windows only at the front, and the space was therefore dependent on toplighting. A winding staircase to the side of the gallery gave access to the priests’ living quarters and ancillary rooms.

Upper level plan, 1886, by Henry Petit, architect. (© Portman Estate)

The chapel was to acquire a number of valuable furnishings and artefacts, but perhaps the most remarkable was the original altar painting of the Annunciation, the work of the Roman Catholic artist Maria Cosway, then living at Stratford Place in Oxford Street, with her husband the miniaturist Richard Cosway. This was destroyed in 1858, when velvet hangings over the altar caught light at the funeral of the Countess de Lavradio, wife of the Portuguese Ambassador.

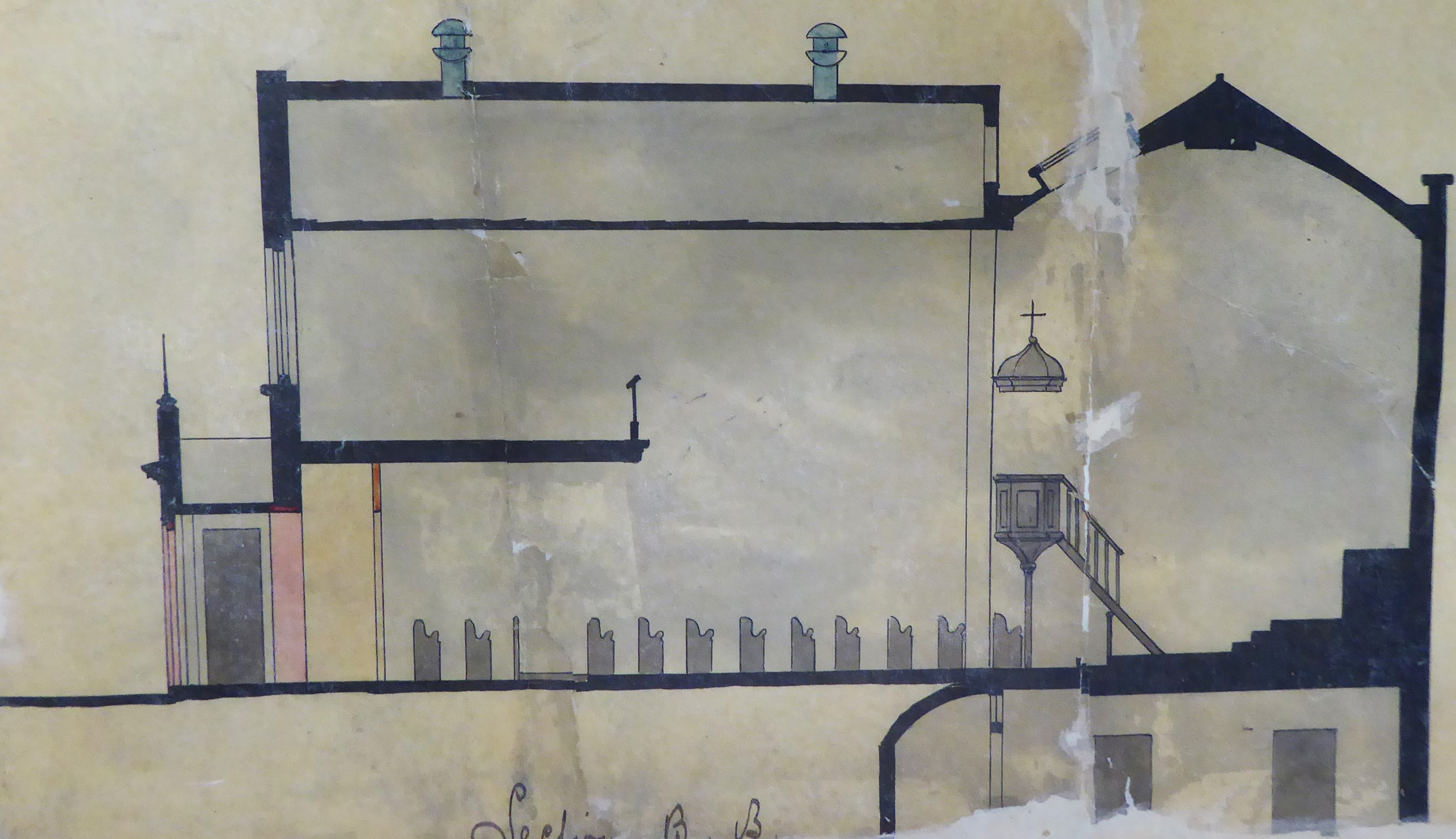

Long section, 1886, by Henry Petit, architect. (© Portman Estate)

By the end of the century, Marylebone was no longer a particular centre of the London French community and the building had largely been superseded by the church of Notre Dame de France in Leicester Place, opened in 1868. Closure followed soon after the death of the long-serving priest, the Very Rev. Louis Toursel or Tersel, in 1910, a final service being held on 12 February 1911. Soon afterwards the seating and other fittings were stripped out. The lease had only a couple of years to run and although there was some negotiation for a new one the unauthorized removal of the fittings caused difficulty and the building was surrendered together with a payment apparently for reinstatement. Later that year the London County Council decided to rename Little George Street after Sydney Carton of A Tale of Two Cities.

Section, 1886, by Henry Petit, architect. (© Portman Estate)

The chapel was used in 1912–14 by Anglicans as their Chapel of the Annunciation, while their church, the former Quebec Chapel on the corner of Bryanston Street and Old Quebec Street, was rebuilt. During the First World War it was used for training women and girls to make toys and gloves, items which until the war had been imported from Germany and Austria. Later it was used as a furniture warehouse, as an undertaker’s chapel and as a public hall, called Carton Hall. From 1946 until the completion of a new synagogue in Crawford Place in 1957 it was occupied as the Western Synagogue, housing a congregation bombed out of their old West End building. In 1958 it was acquired by Angus McKenzie, who employed the cinema architect Leslie C. Norton to turn it into the original Olympic Sound Studios. Recordings made there included Millie Small’s ‘My Boy Lollipop’ in 1964. By that time redevelopment schemes for the whole block were being pursued. The building was demolished in 1969 and Carton Street itself ceased to exist.

Maria Cosway’s altarpiece painting. Mezzotint of 1800 by Valentine Green. (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Doorcases in South-East Marylebone

By the Survey of London, on 27 July 2018

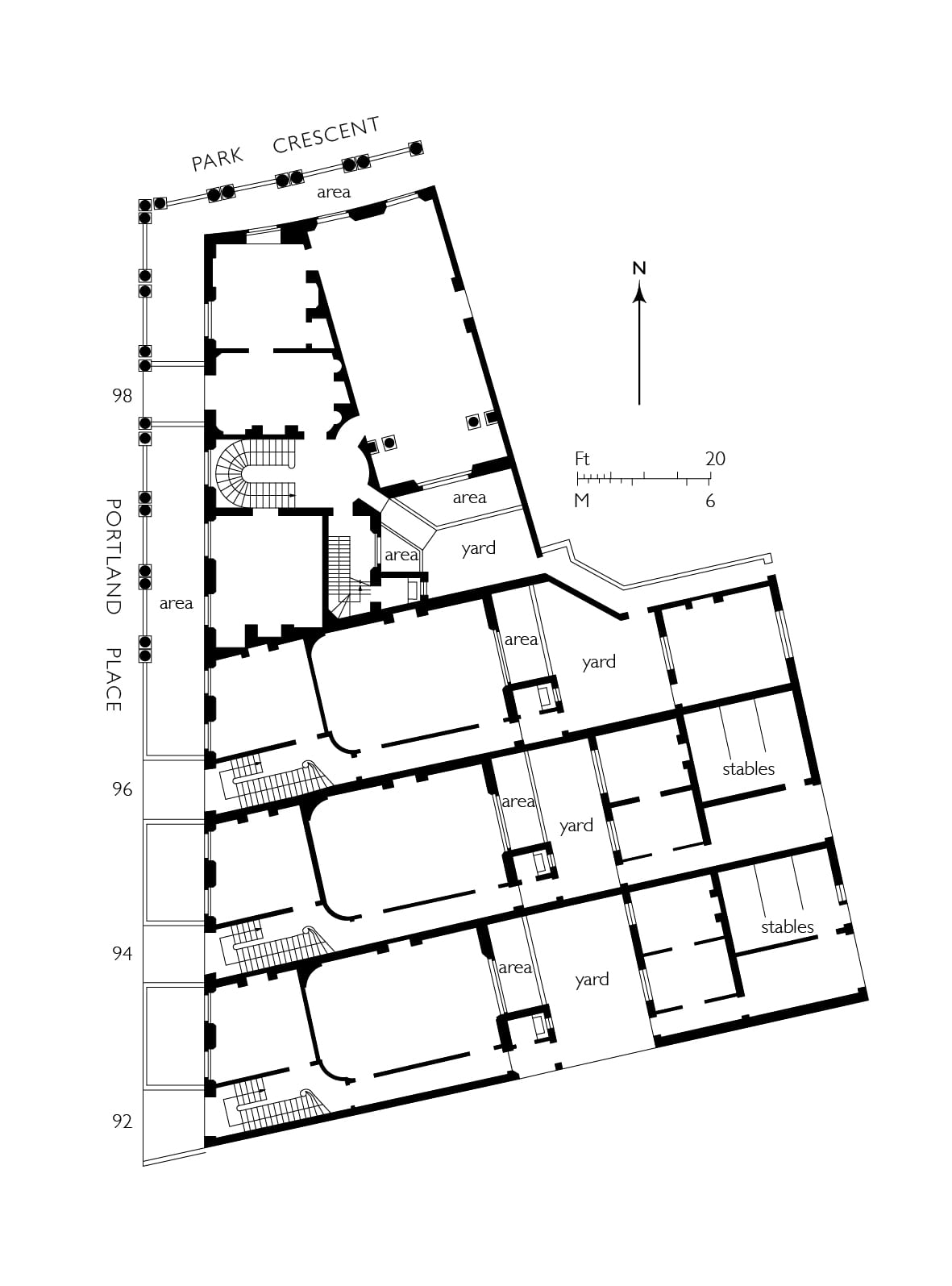

In 2017 the Survey of London published two volumes (Nos 51 and 52) covering South-East Marylebone, an area comprising much of the West End north of Oxford Street. Historically and architecturally, this is an area of extraordinary richness and variety, resonant with famous names and associations, from the Adam brothers’ Portland Place and Nash’s Park Crescent to the medical specialists of Harley and Wimpole Streets, and much more besides.

We would like to present here a varied assortment of doorcases in the area, from handsome eighteenth-century survivals and neo-Georgian designs, to plain doorways for blocks of modest flats and elaborate entrances for shops and institutions.

Hereafter, the Survey of London’s blog will take a summer break. Posts will resume in September.

Mansfield Street was laid out by the Adams on the Portland estate from c.1768, and was largely complete by 1772. Elevationally the Mansfield Street houses were typical of the Adams’ approach to terrace compositions, with the exteriors generally subservient architecturally to the interiors. The plain but elegantly proportioned brick façades resembled the less-decorative ranges of the Adelphi, any ornament being reserved for the entrance door surrounds. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

13 Mansfield Street and other neighbouring houses exhibit an early use of one of Robert Adam’s most successful designs for street architecture – a grand door surround with a wide semicircular fanlight comprising concentric inner and outer rings of delicate glazing, but extending beyond the width of the doorway to embrace slim rectangular side-lights. There are obvious similarities with Serliana, but it has been suggested that Adam derived this idea of a wide semicircle from the Porta Aurea of Diocletian’s Palace in Spalatro (now Split). It was a form that recurred throughout his work, both externally and in internal features, such as mirrors. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

29 Beaumont Street, a house built c.1890 for the livery-stableman William Burton, with an elaborate entrance in rubbed brick. Burton ran livery stables and a horse dealership in Marylebone High Street from 1857. From about 1872 he was also operating as a job master from stables in Paddington and Notting Hill, and in 1877 in Oxford Street. By the late 1880s the Marylebone stables were mostly or wholly used for dealing, and in 1890–1 Burton had them rebuilt, together with a saddler’s shop (now 30 Beaumont Street) and a house for his family (now 29 Beaumont Street). Thomas Durrans was the architect, and H. C. Clifton of Bayswater the contractor. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

93A Harley Street (Harley Lodge), frontage to Weymouth Street. This is a fine example of the double-fronted mews house rebuildings, this time of the early 1900s. Like its dourer stone-fronted equivalent at 90A Harley Street, it was designed in 1911 for the developer Charles Peczenick by Sydney Tatchell, but on this occasion in a more playful red-brick and stone neo-Georgian manner, with a semicircular-headed entrance set in an Ionic doorcase. In medical use from the beginning, it is now, like many of its type, a private dental surgery. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

This purpose-built institute and club connected with the Mission of the Good Shepherd in Paddington Street was designed by the architect and vestryman Thomas Harris. The foundation stone was laid by the Duchess of Portland in July 1898 and the completed premises, built by H. H. Sherwin of Waddesdon, were opened in January 1900 by the Duke and Duchess of Fife. For the front elevation Harris produced an interesting and eclectic design, executed in red sand-faced brick interlarded with blocks of buff terracotta produced by J. C. Edwards of Ruabon. Though the overall manner is Arts and Crafts, Gothic is there in the ogees over the windows and emphatically in the canopied figure of the Good Shepherd, sculpted by John Daymond III or possibly his son John Dudley Daymond. It is mounted over a panel of arty lettering. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

In 1923–4, 17 Cavendish Square was taken by the piano-makers John Brinsmead & Sons Ltd, previously across Wigmore Street, and an ostentatious refurbishment ensued. The architects T. P. Bennett & Hossack oversaw the Adamesque stucco embellishment of the Wigmore Street elevation with a new entrance and shopfront. Gilbert Bayes was the sculptor responsible for lower-storey reliefs of classically draped standing figures representing Science, Music and Art, and a panel depicting an orchestra of eleven naked child musicians. These received gushing encomiums – ‘a delightful conceit’, ‘a captivating piece of work’, and an eight-page spread in the Architects’ Journal. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

4 Moxon Street (formerly known as Paradise Place) incorporates a plain doorcase and a gateway designed to give access to the premises of W. N. Davis, of Davis & Son, old-established dyers and cleaners with adjoining premises at 91 Marylebone High Street. Davis’s architect was E. V. New of New & Son. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

View of the entrance to 4 Moxon Street. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

11 Queen Anne Street was one of ten houses built by George Mercer between Chandos Street and Harley Street, and completed in 1764. From 1777 to 1780, the house was nominally occupied by ‘the Wicked Lord’, Lord William Byron, great uncle of the poet, but it is doubtful whether he spent much time there. The timber doorcase to this house, Doric columned with a deep open pediment, is similar to that at No. 24. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)