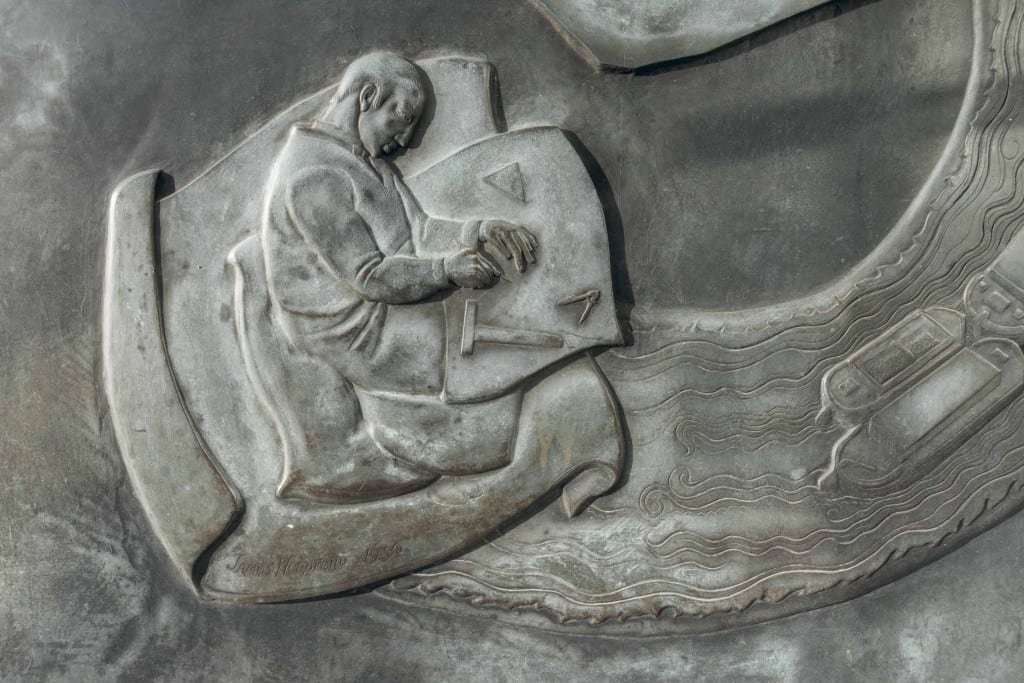

The name of D. H. Evans disappeared from Oxford Street in 2001, though it lingers in the memory of many. Since then it has been a branch of the House of Fraser, the company which has owned the store since 1954. Just over eighty years ago the present store was completed, officially opened in February 1937. It was designed by Louis Blanc in 1934 and constructed in two phases so that trading could carry on with as little interruption as possible. When it was completed, it made a dramatic impact, occupying an entire block, and rising higher than any of the other shops then standing on Oxford Street.

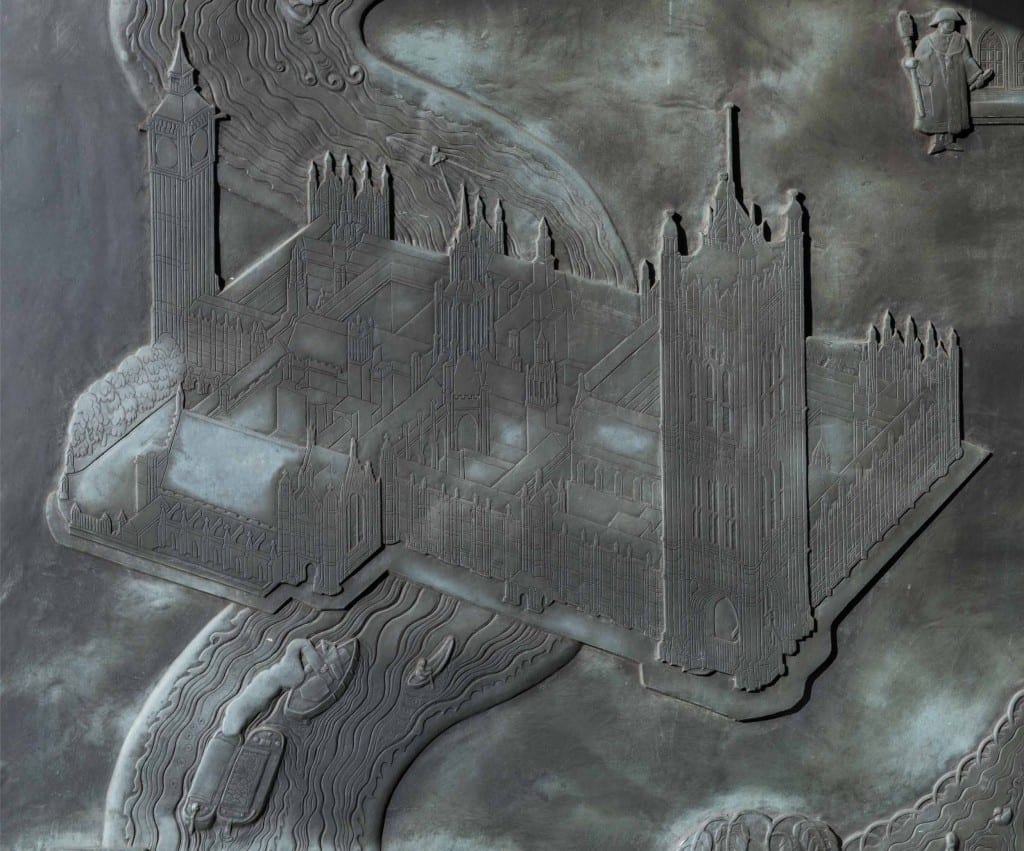

Cover of the Coronation Brochure produced by D. H. Evans in 1937, with their new store circled, and showing how much higher it was than its neighbours along Oxford Street.

With the coronation of George VI and Queen Elizabeth taking place on 12 May that year, the management of D. H. Evans produced a commemorative brochure for the occasion, which principally served as a promotion for their new store. Traditionally Oxford Street was included in royal processions, and the coronation that year was no exception. The street was part of a six-mile route taken by the new king and queen after their coronation from Westminster Abbey to Buckingham Palace. Some press reports estimated that six million people descended on London for the occasion. All the shops were decorated with special window displays, and the street enlivened with flags and flowers. Royal monograms and coloured streamers abounded.

Perspective view of D. H. Evans from the Coronation Brochure.

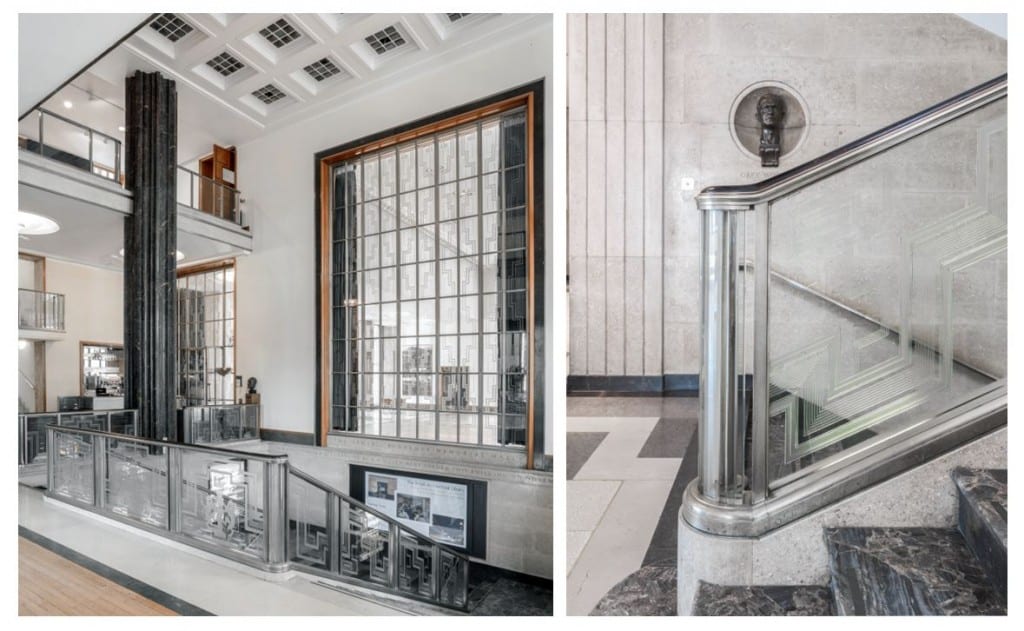

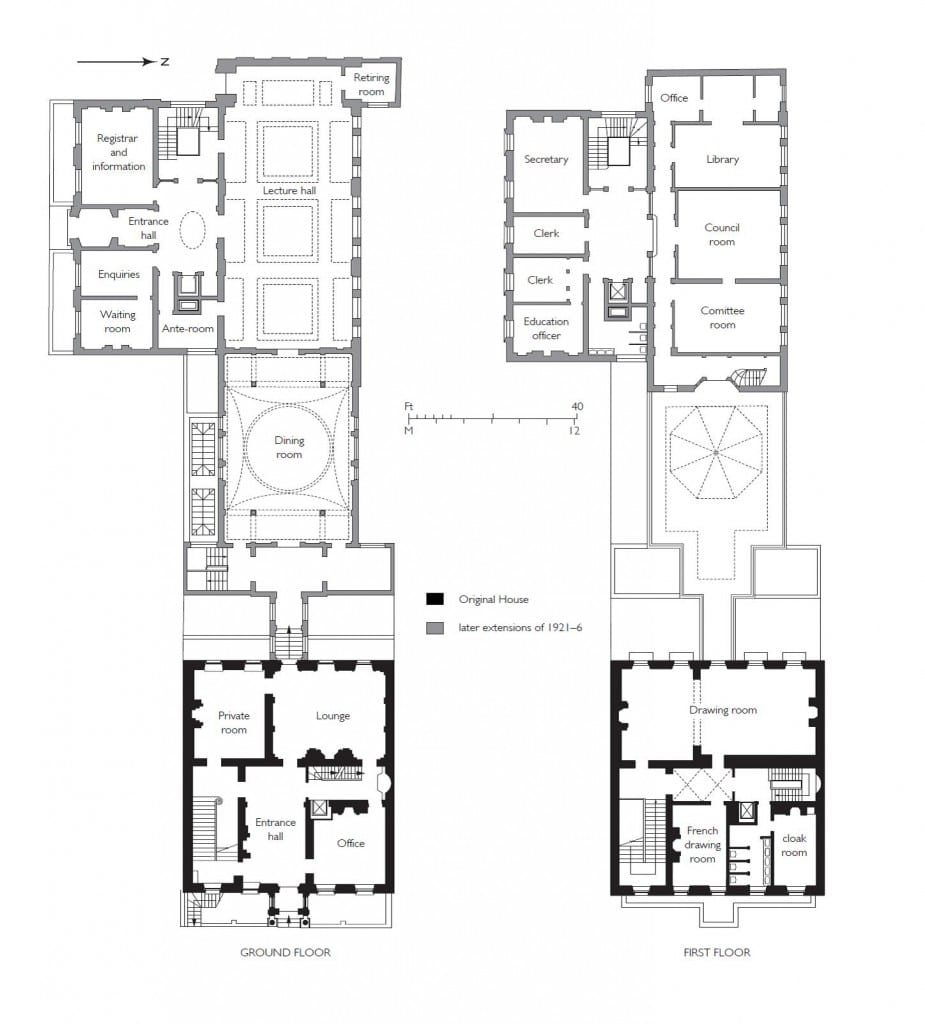

Recent relaxation of the height restrictions imposed on trade buildings by the London Building Acts enabled the new store to rise to 100 feet, twenty foot more than the old limit and productive of an additional two storeys. The building was steel-framed, with solid concrete floors and faced in Portland stone above the pale-grey granite facing of the ground storey. The great height of the building gave it presence on the street and produced one of its most exciting spaces inside in the form of the escalator hall. This contained not just the sequence of escalators but also staircases and ‘high-speed’ lifts (the upper trading floor could be reached in one and a half minutes).

Escalator Hall, D. H. Evans, from the 1937 Coronation Brochure

In its finish and colour the escalator hall was also intended to be a glamorous focal point, a place to be seen, as well as from which to view all the store had to offer. The walls and pillars were of delicate beige-pink Travertine marble, the floors of polished cork, producing a ‘soft, brown glow’, the fibrous plaster ceiling was in a ‘modernistic design’, the sheen of metalwork on stairs, escalators and lifts was achieved in ‘silver and copper bronze surfaces, satin finished’.

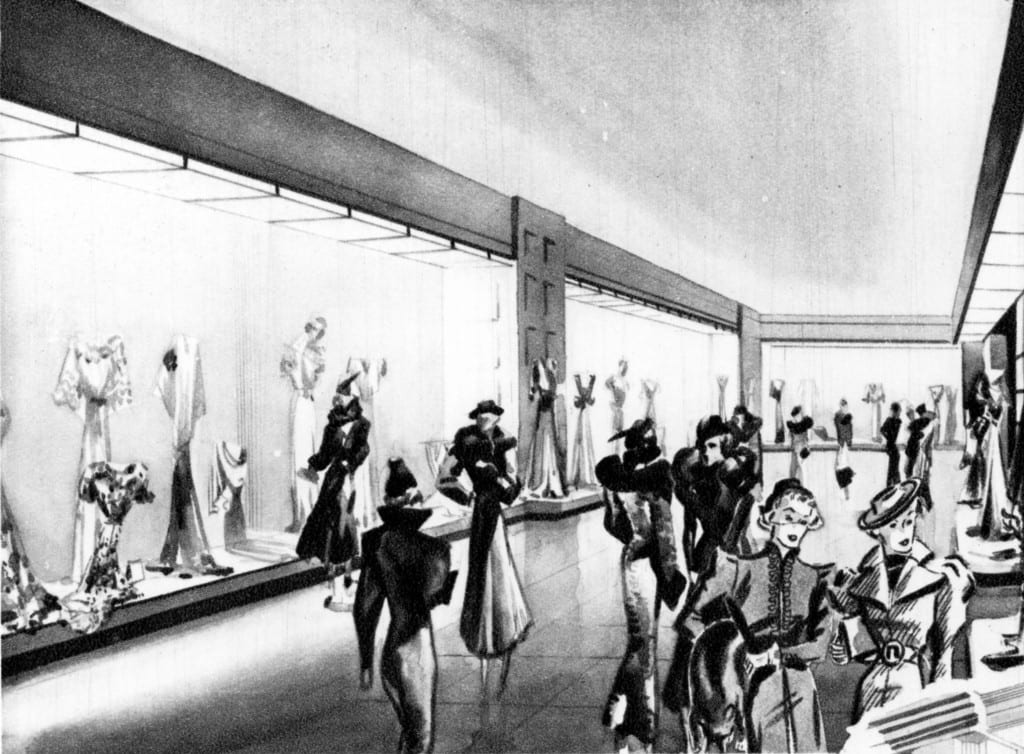

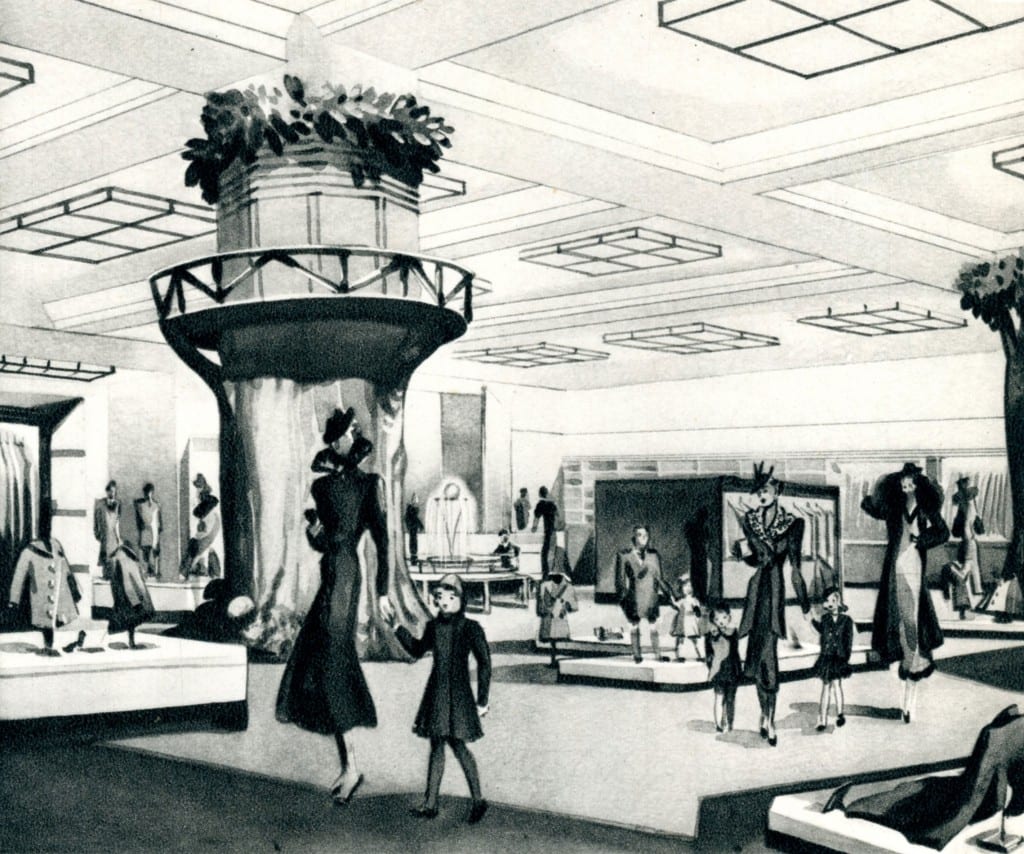

Ground Floor, D. H. Evans, with the impossibly angular largely female shoppers parading along the wide aisles between display stands.

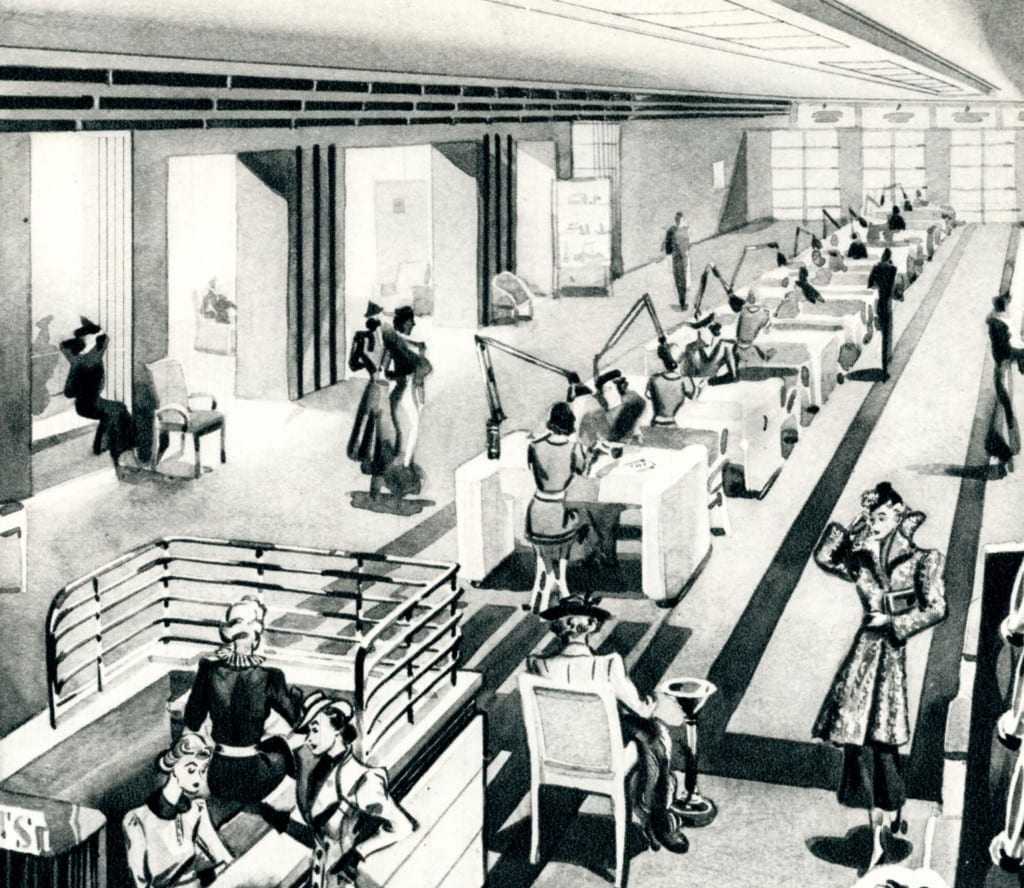

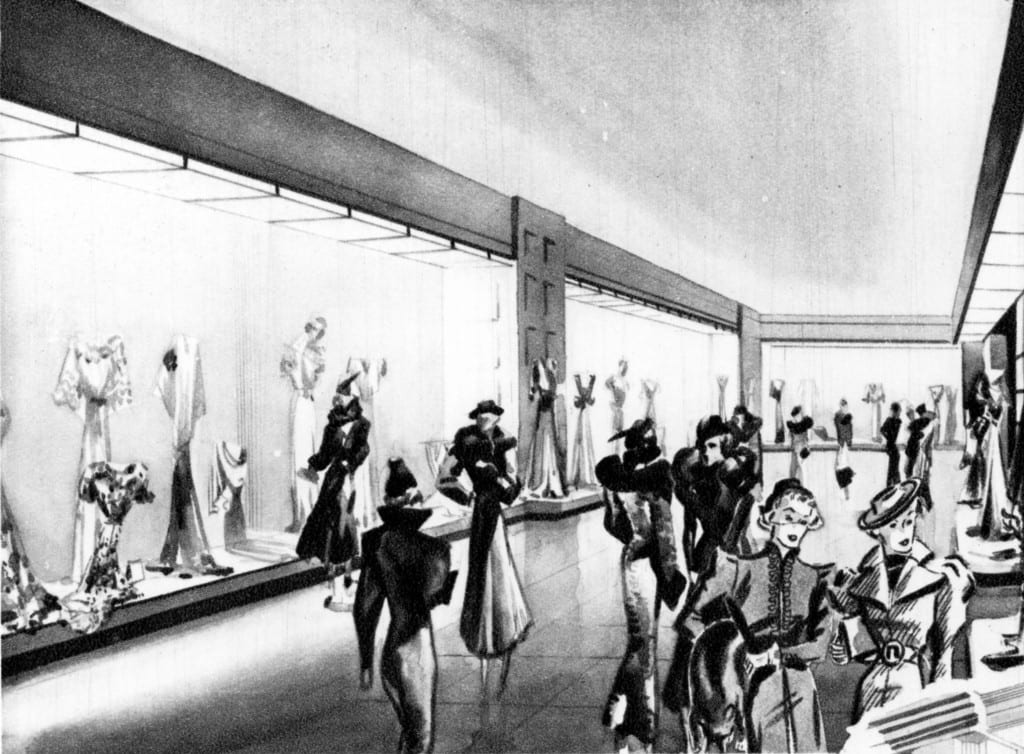

There were six trading floors. On the ground floor were fashion accessories and fabrics arranged either side of a sweeping central aisle. Branching from each side ‘miniature, self-contained shops’ sold specific accessories or goods: stockings, gloves, handbags, lace, jewellery, perfume, fur trimmings, scarves, haberdashery, needlework, flowers, wools, or household stationery, each defined beneath its own canopy, with diffused light illuminating the merchandise displayed beneath. Fabrics had a larger area, occupying the rear half of the floor with separate sections for different types of material: plain silks, printed silks, tweeds, woollens, cottons, and lingerie fabric (staffed entirely by women). Here were also dress-making patterns, staffed by ‘expert saleswomen’ capable of giving sound and practical advice.

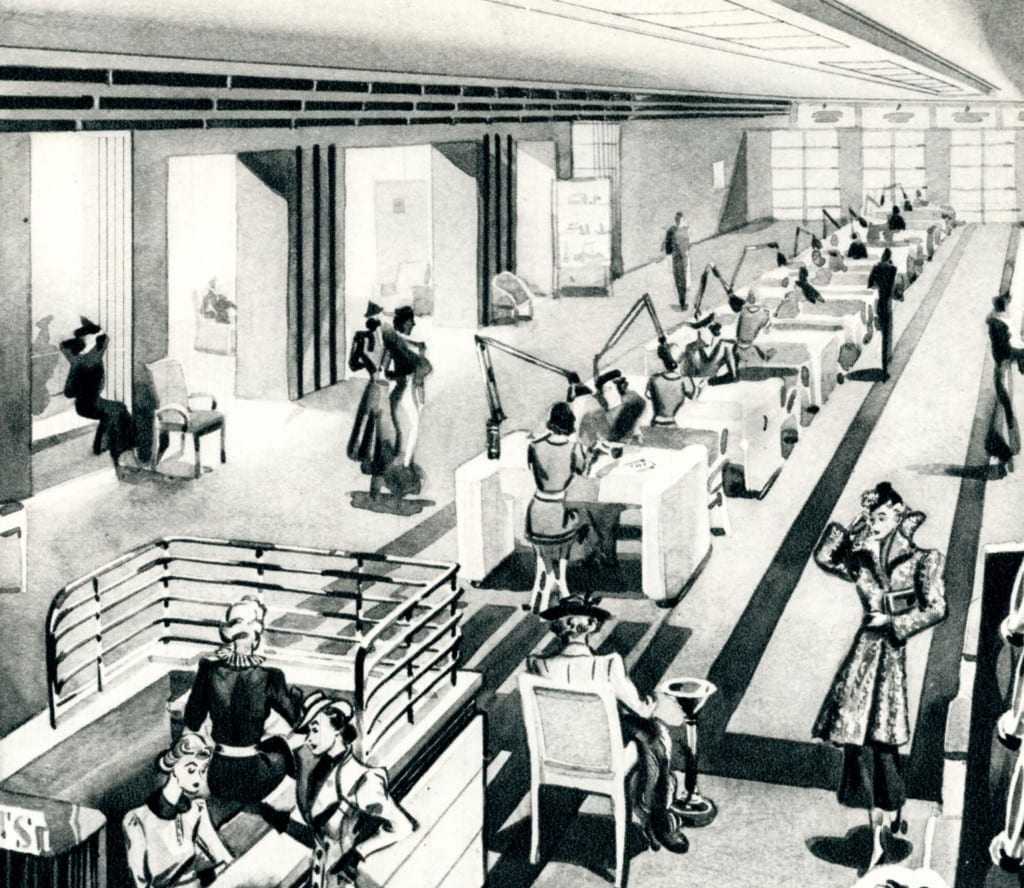

One of the ‘display corridors’, bringing window shopping indoors.

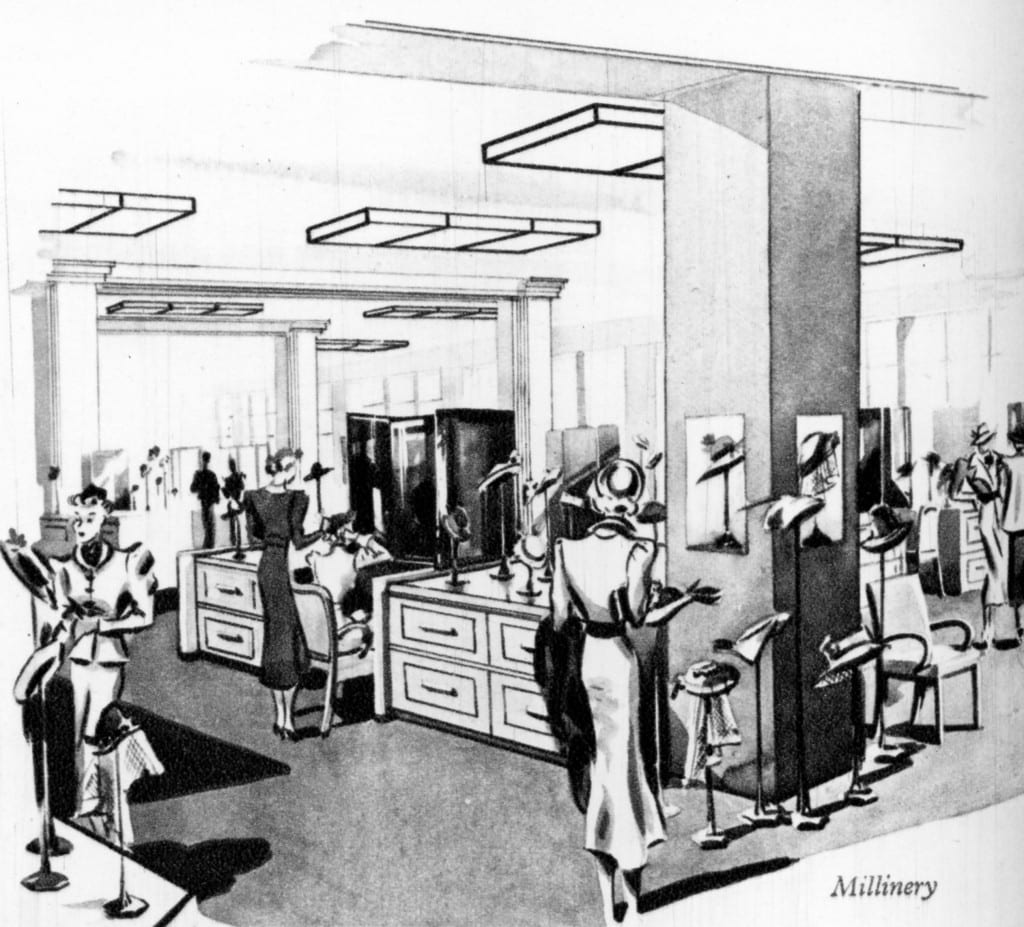

The first floor was divided into three sections devoted to the principal items of women’s clothing: the hat, the coat and the frock. Display corridors ran around the floor designed to look like shop windows. Thought was given to the way in which people shopped in the arrangement of goods, so they were divided into price groups and size, but also for quick or slow shoppers.

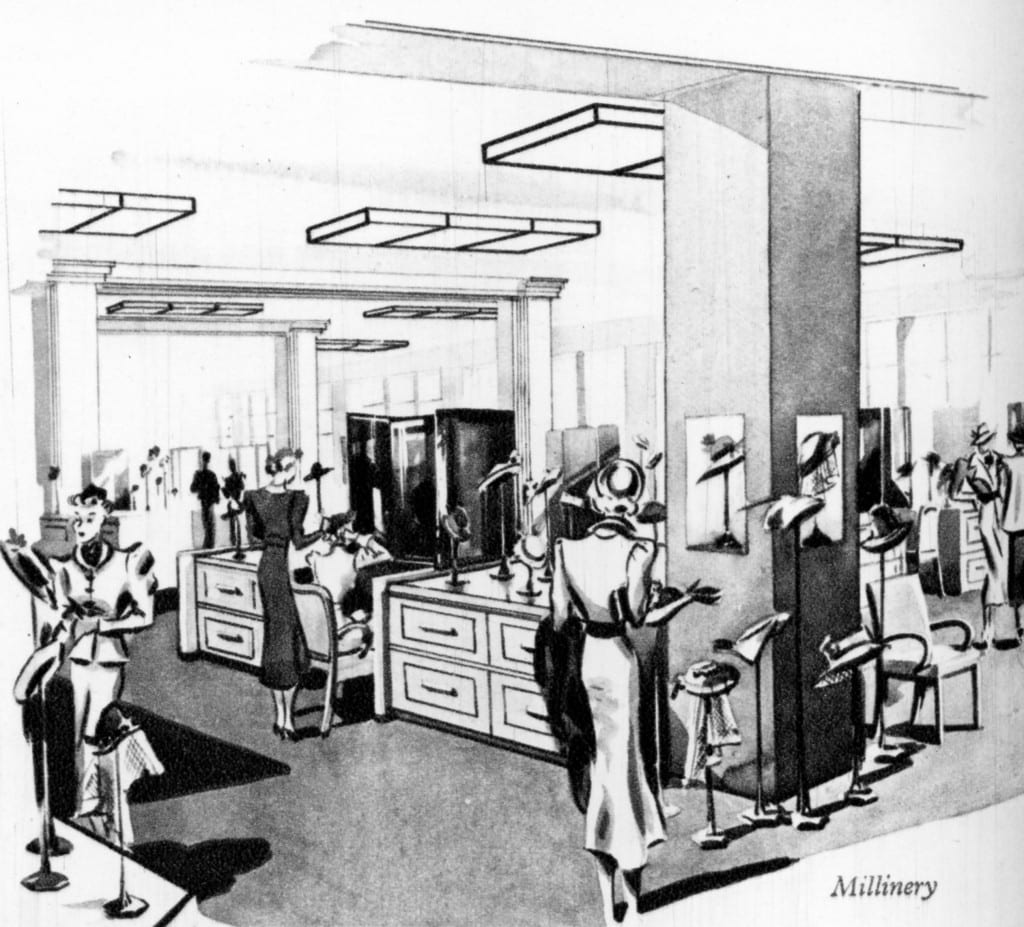

Millinery department, where different areas were adapted to differing habits of the shoppers, whether they were fast or slow.

Hats were arranged on tall counters for quick shoppers, and mirrored alcoves for those wishing to make a leisured choice. A separate room was set aside for three-piece suits, and private fitting rooms, luxuriously appointed, were provided ‘in plenty’.

The corset department.

Underwear, including night-clothes, was on the second floor. More display corridors lead to blouses and knitted jumpers, placed ‘for matching purposes, next to skirts. Knitted suits were in a separate room, and ‘tailormades’ supervised by a specialist tailor. Here too were shoes, furs, and bathing and beach wear. Furs were displayed against a background of Indian white mahogany, and there was a fur storage section resembling a small bank, with a vault of its own, while the cold storage in the sub-basement could store ‘many thousands of pounds worth’.

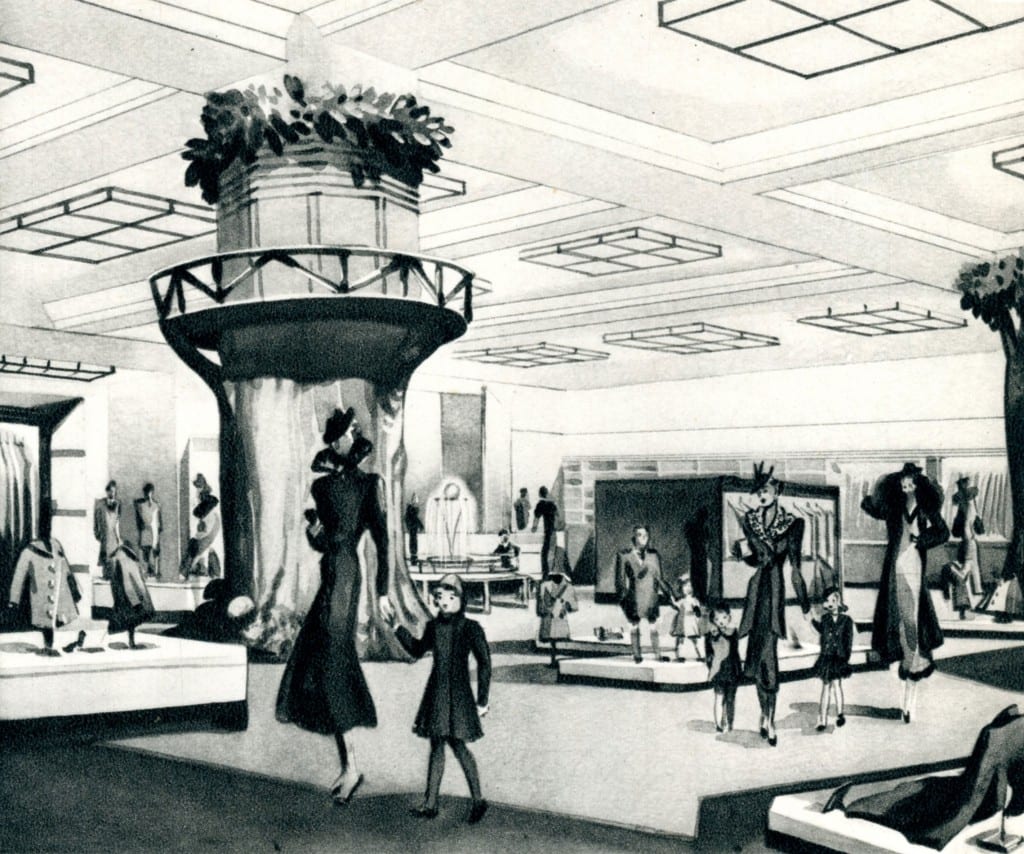

The children’s department, which featured Peter Pan’s Playground. ‘The houses of Peter Pan and Wendy take the form of two huge trees which spread their branches over an enchanting ornamental pond and fountain.’

The third floor contained three quite separate sections: the children’s department, household and travel. The children’s department was the largest, taking up about two thirds of the floor and not only selling outfits but also providing two playrooms for the under-sixes – Peter Pan’s Playground (see above).

The Baby Shop

The travel section sold school trunks, suit cases, rugs, foot muffs and ladies’ weather-coats and mackintoshes, while the household section included overalls, utility frocks, maids’ and nannies’ outfitting as well as bed- and table-linen etc.

The beauty salon, offering sound-proof beauty rooms.

Half of the fourth floor was devoted to hairdressing and beauty salons, boasting ‘an all British staff’. All cubicles had padded comfort chairs, spring rests for the feet, a telephone, and sterilising cabinets – for disinfecting the instruments of beauty treatments. For beauty culture there were nine sound-proof beauty rooms with day or night lighting. Materials used were prepared in the company’s own laboratories, adjoining which were workrooms for the production of postiche. The rest of the floor was given over to the gifts department.

The restaurant on the fifth floor.

The fifth floor was the highest one devoted to the public and contained the restaurant. Furnished in brown, beige and rose, down both sides were plush-seated alcoves while the rest of the floor had circular tables arranged in a grid of squares around the supporting columns, around the base of which were waitressing stations. The restaurant offered table d’hôte and à la carte meals, while a salad and sandwich room catered for customers with less time to linger. Two kitchens, one at either end, were fitted out with all the latest appliances.

Ladies who lunch – enjoying a lettuce leaf or two, and a cigarette, in the fifth-floor restaurant at D. H. Evans in 1937

Sources

The Builder, 8 Jan 1937, p.122; Coronation brochure, 1937

Close

Close

![The Langham Hotel (by The Langham, London, reproduced with a Creative Commons licence via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)])](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/survey-of-london/files/2016/03/Langham-Wikipedia-Commons.jpg)