The Queen’s Hall, Langham Place

By the Survey of London, on 12 February 2016

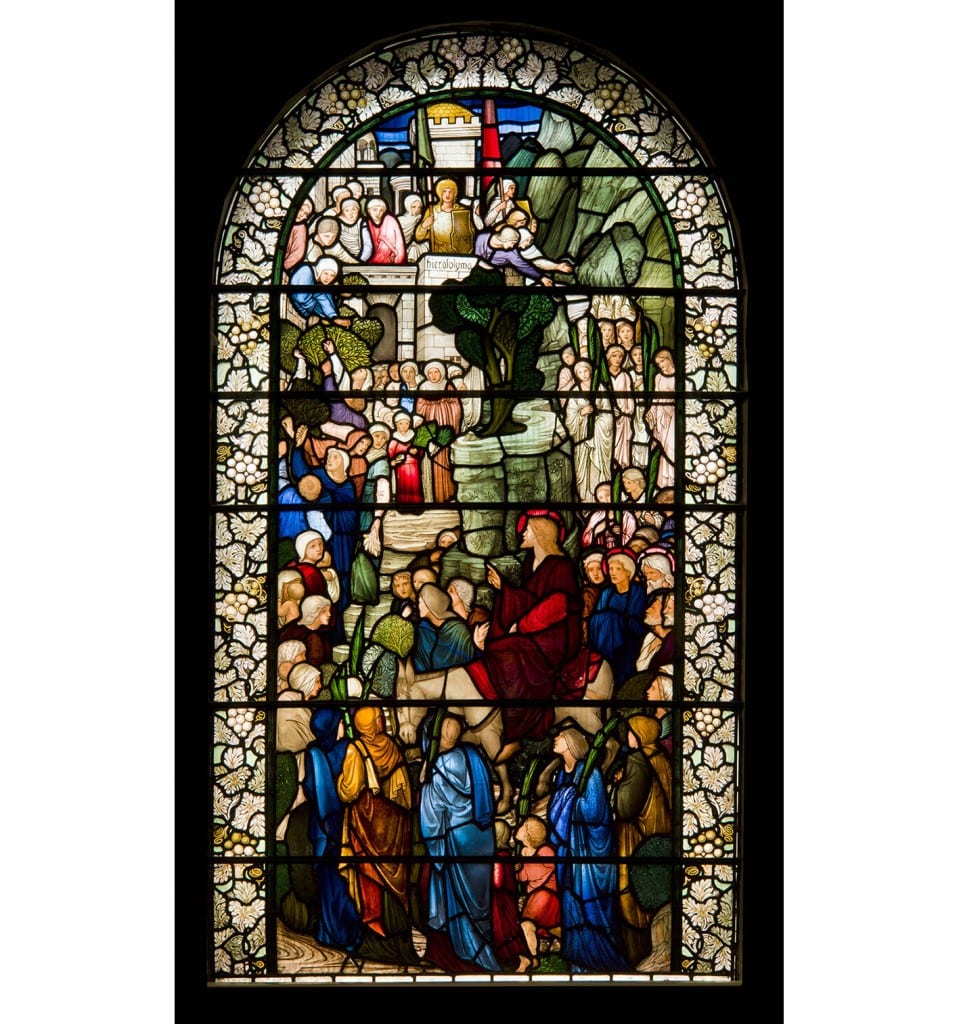

Portrait busts of great composers lying amidst rubble after the Queen’s Hall was hit by an incendiary bomb in 1941 (Photograph by Larkin Brothers Ltd., reproduced by kind permission of the Royal Academy of Music). If you are having trouble viewing images, please click here.

Handel, Haydn and Weber lying with other great composers’ names and profiles amidst ruin and dereliction: this poignant photo, taken around 1954, shows remnants of the Queen’s Hall, Langham Place, Marylebone, at the time of its final demolition. The building had been gutted by an incendiary bomb on the night of 10 May 1941, but like many blitzed buildings in London its shell lingered on into the 1950s.

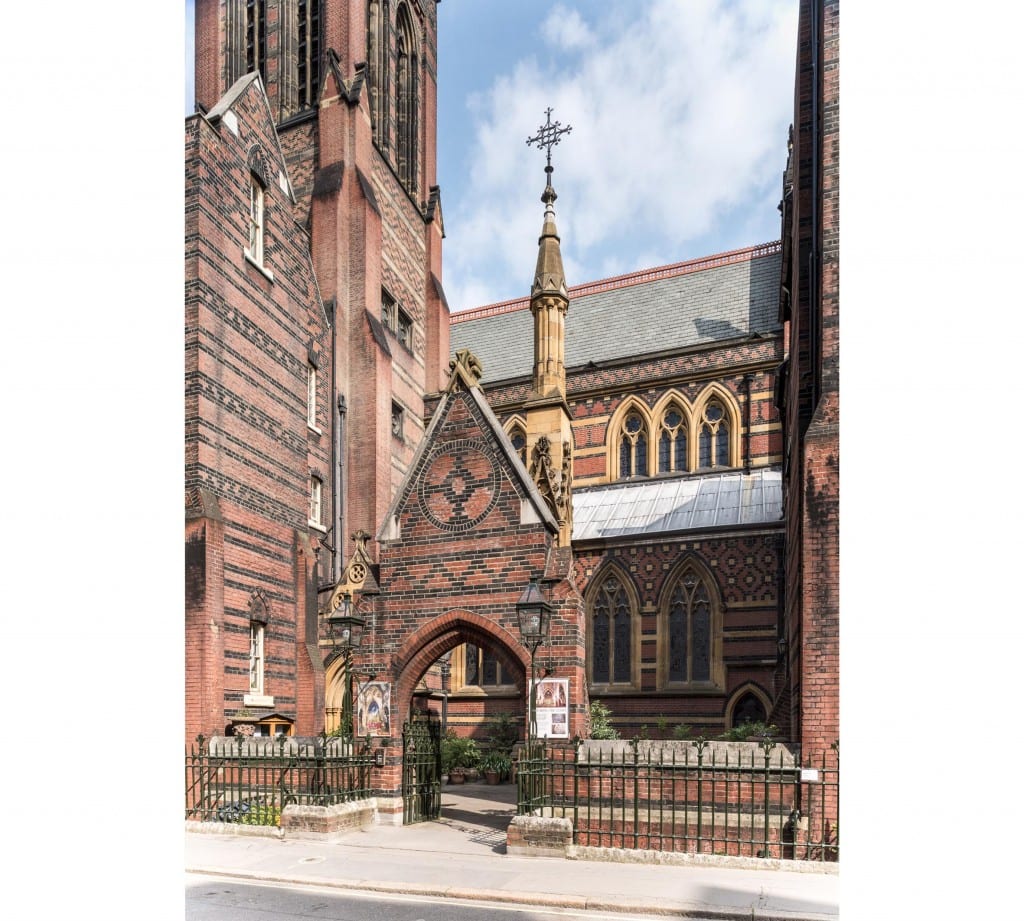

The Queen’s Hall was the perfect concert hall for London’s musical life, something which now only a very few can remember. Famously, it was the first home of the Proms. Everyone who played or sang or went to concerts there recalled its intimate atmosphere and acoustics with great affection. Before it was built in 1890–3, large-scale orchestral or choral concerts and recitals were held in multi-purpose halls like St James’s Hall, Piccadilly, with few facilities for performers and little by way of outward architectural show.

The Queen’s Hall seen from Langham Place, photographed in 1894 by Bedford Lemere and Co. (Reproduced by kind permission of Historic England).

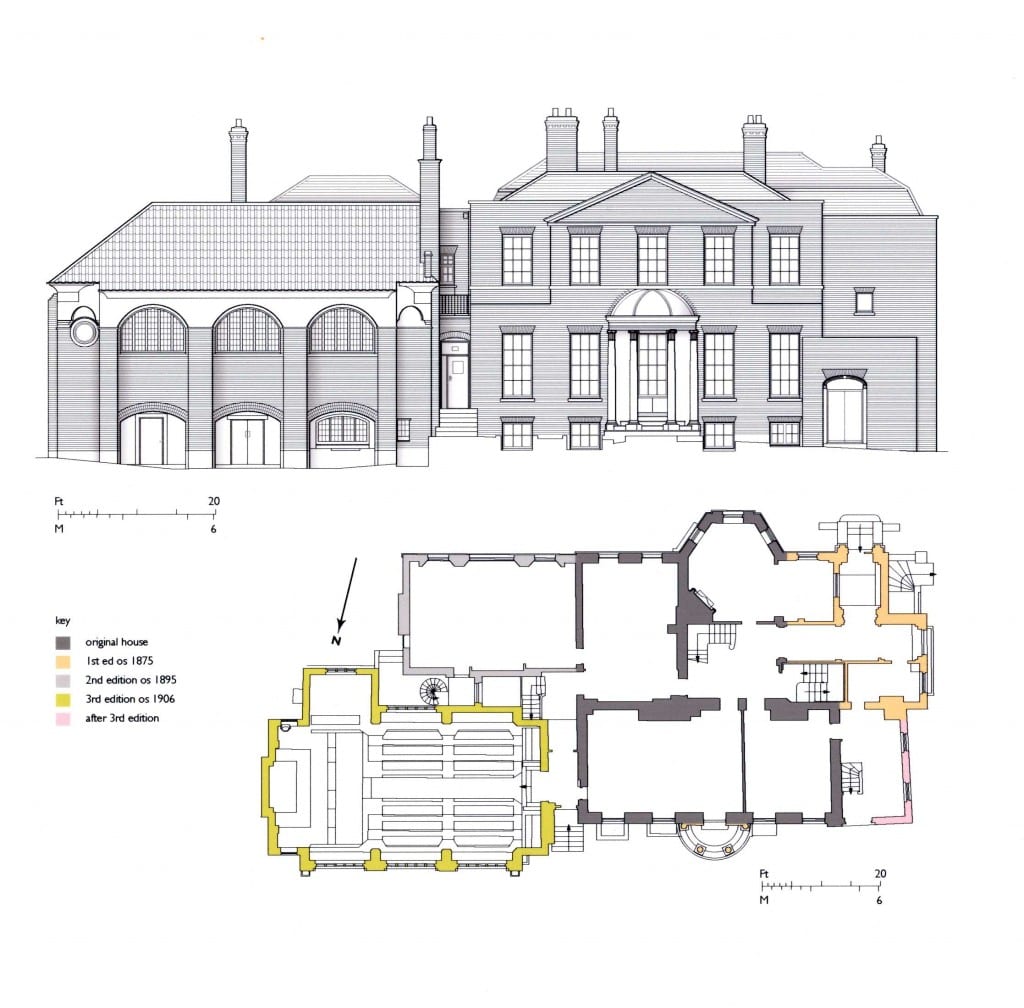

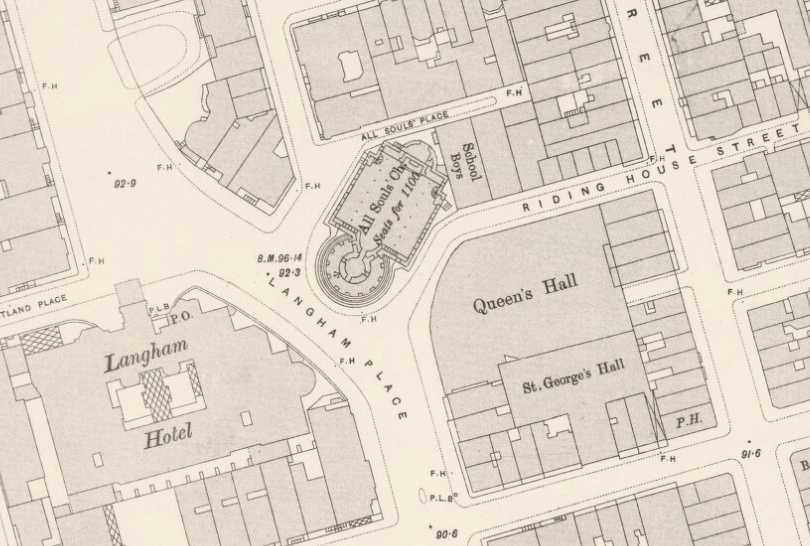

The Queen’s Hall was different. Projected on a prominent site between All Souls, Langham Place and another forgotten musical venue, St George’s Hall, it was built at the sole expense of Francis Ravenscroft, who had made a great deal of money from the Birkbeck Bank. Ravenscroft seems to have had no special interest in music, but his lawyer J. S. Rubinstein did, and it is a fair bet that the idea to invest his client’s money in a modern concert hall for London came from him. Once that decision had been taken, Ravenscroft did not stint, giving his main architect, T. E. Knightley, the chance to design not only a grand concert hall to a horseshoe plan with a smaller recital room on top, but also a spectacularly lavish monumental frontage in stone on a curve, with a deep colonnade and lashings of carving. It was there, tucked into niches, that the composers featured, some as complete busts, others in high profile.

Extract from the 2nd-edition OS map, published 1895, showing Langham Place with the Queen’s Hall next to All Soul’s church and opposite the Langham Hotel (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland).

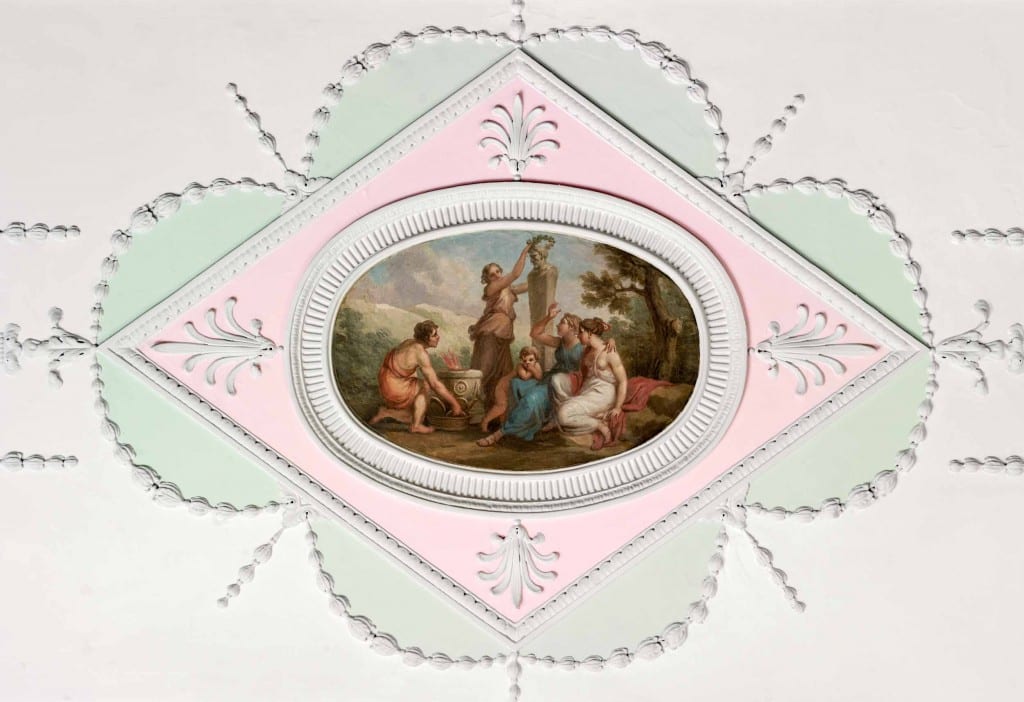

The photograph at the top of the page shows only some of the abandoned composers in profile (the complete set consisted of Brahms, Gluck, Handel, Mendelssohn, Wagner and Weber). By then the full busts (Bach, Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Purcell and Tchaikovsky) had probably been rescued by the St Marylebone Society with the aid of the Royal Academy of Music. For years they adorned the garden of a cottage in Olney, Buckinghamshire, shared by the violinist and teacher Rosemary Rapaport and Sir Thomas Armstrong, former Principal of the Royal Academy of Music. They were returned to the Academy in 2001 after restoration, and can now be seen in its museum on the Marylebone Road. They are the sole physical reminders of a famous and much-loved London institution, where leading musicians from all over the world played and many famous meetings were also held. The best evocation of the Queen’s Hall and its atmosphere can be found in E. M. Forster’s Howards End, including a nicely sarcastic description of its French ceiling painting showing ‘attenuated Cupids … clad in sallow pantaloons’. That had been painted out well before the fatal bombing of 1941.

Close

Close