‘The Thirteen’

‘The Thirteen’

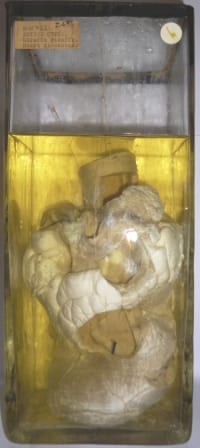

The collection of specimens, known since 1997 as the Grant Museum of Zoology, was started in 1827 by Robert E. Grant. Grant was the first professor of zoology at UCL when it opened, then called the University of London, and he stayed in post until his death in 1874. The collections have seen a total of 13 academics in the lineage of collections care throughout the 187 year history of the Grant Museum, from Robert E. Grant himself, through to our current Curator Mark Carnall.

Both Grant and many of his successors have expanded the collections according to their own interests, which makes for a fascinating historical account of the development of the Museums’ collections. This mini-series will look at each of The Thirteen in turn, starting with Grant himself, and giving examples where possible, of specimens that can be traced back to their time at UCL. Previous editions can be found here.

Number Four: Walter Frank Raphael Weldon (1891-1899) (more…)

Number Four: Walter Frank Raphael Weldon (1891-1899) (more…)

Filed under Grant Museum of Zoology

Tags: Chair of zoology, Collections, Curator, Dugong, E. Ray Lankester, Grant Museum history, Horseshoe crab, Limulus, Manatee, On the Origin of Our Specimens, Specimens

No Comments »

Close

Close