We’re all heart at the Grant Museum

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 14 February 2014

No matter who you are or where you come from, you have to admire the giraffe’s heart. It manages to pump blood up arteries in a neck that can reach over two metres in length. It is helped out by a series of valves that prevent the blood from flowing back down again (except through the veins, in which it is supposed to flow back down again). The giraffe’s heart is, surprisingly, smaller than that of mammals of a comparative body size. The heart copes with the morphology of the animal by having really thick muscle walls and a small radius. The result is a very powerful organ. I wonder if that means giraffes fall in love really easily, or find it harder to get over their exes?

Despite the seemingly counterintuitive appearance, the elephant heart is not a model, but a real organ. The heart has been dried and the veins and arteries injected with, we think, some form of resin before being painted to really stand out. When the heart first came to the Museum it was not recorded what species of elephant it had belonged to so is currently labelled as Elephantidae. African savannah elephants (Loxodonta africana) are the largest, followed by Indian elephants (Elephas maximus), and African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) are the smallest. The heart of an African elephant can weigh up to 21 kg, which is approximately equivalent to 42 medium sized Valentine’s Day boxes of chocolates.

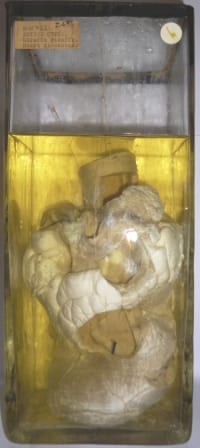

The preserved mantis shrimp heart

The preserved mantis shrimp heart

The mantis shrimp has one of the fastest responses known to man and can strike with the force of a bullet. For an animal with a maximum body length of a few cm up to 30 cm (species dependent, of which there are over 400), I’d say that’s pretty impressive. Amongst crustaceans, the heart of stomatopods (the group to which the mantis shrimp belongs) is unique for its simplicity. Despite that, love for the mantis shrimps is not a simple or black and white issue. Some species are monogamous and mate for life meaning Valentine’s Day is presumably full of love and romance. Other species of mantis shrimp however are far more carefree and highly promiscuous making Valentine’s Day a little less special. Or else hectic and expensive.

Because of its herbivorous diet and grazing behaviour, dugongs are also called sea cows. The heart of the dugong sits in a perpendicular plane to the lungs, unlike cows, though there are easier ways to differentiate between the two than dissecting them. The dugong’s closest relative is the manatee, which look pretty similar I think you’ll agree. In terms of their hearts however, the dugong has a deeper interventricular cleft (the bit between the top and tail pears at the bottom of the image of the model on the right) and the left ventricle (the upside-down pear) is more conical than that of the manatee. As sedentary as dugongs seem, it is thought that these characteristics have evolved as part of the dugong’s specialisation for ‘a more energetic aquatic lifestyle’. Perhaps their extra energy production is for mating, they seem to be fans of ‘tough love’. Dugongs are boisterous lovers and have a knack of using their tusks in the process, leaving both males and females scarred. The female will mate with several males one after the other. How very romantic.

The plethora of platypus hearts

The plethora of platypus hearts

The platypus wins my heart, my house is covered in (soft toy) platypodes (technical term for the plural) and in 2010 I had the life changing pleasure of holding a live platypus in the platypusary (world’s best word) at the Australian Reptile Park near Sydney in Australia. To continue with the subject of platypus hearts rather than my own however, the platypus heart is a mere 35 mm in length, but then platypuses (non-technical but most commonly used term for the plural) themselves are only around 50 cm from bill tip to tail tip. When it comes to matters of the heart, platypuses are not monogamous, but they are romantics in their courtship. The male and female will engage in a sensuous ‘wining and dining’ stage with increased body contact, and nuzzling their bills together. They mate underwater after a period of circling around one another with the male often holding on to the female’s tail with his bill. Awww, how sweet.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close