The Anthropologist, the Anatomist, and the Highwayman: Stories from student research 2020/21

By ucwehlc, on 21 July 2021

Teaching with museum objects during a global pandemic has been something of a challenge, to say the least. You can read more about how the UCL Museums have tackled it in this previous blog.

One of the real success stories has been how UCL students have continued to research objects for their projects without being able to visit the objects in real life, and with reduced access to resources in other museums, libraries, and archives. Their perseverance and ingenuity this year has allowed them to uncover compelling stories of tragedy, prejudice, and redemption in the UCL Science Collections. As the academic year comes to an end, and I add their findings to our database, I thought I would share a few with you.

Eye Colour Gauge by Rudolf Martin: The Anthropologist’s Story

Museum Studies master’s students Karolina Pekala, Helena Smith Parucker, Ailsa Hendry and Emma McKean researched this object for their Collections Curatorship module. Before their project began, we knew that the eye gauge had been designed by someone called Rudolf Martin, and that it had been owned by either Francis Galton or Karl Pearson, both of whom were instrumental in establishing the world’s first Eugenics Department at UCL.

The object itself has an unsettling look to it, even before we consider its links to the history of eugenics. It was designed by Swiss anthropologist Rudolf Martin and manufactured between 1903 and 1907. The students examined Martin’s background and his views on the developing field of eugenics in the early 20th century. They concluded that Martin himself was not actively involved in eugenic research, being more interested in developing methods for accurately measuring humans. However, he was well aware what other researchers were using his methods and tools for, and he supported racially biased anthropological research.

This particular eye gauge was used by Karl Pearson and Margaret Moul in eugenic research on Jewish school boys in London in the 1920s. A later version of the eye gauge was used in German research in the Tarnów Ghetto in Poland in the 1930s.

This story has a tragic sting in the tail for the Martin family. Rudolf Martin died in 1925, so he did not live to see eugenics lead to the horrors of the Holocaust. His second wife Dr Stefanie Martin-Oppenheim survived him, but as she was Jewish, she was imprisoned in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp, where she died in 1940.

You can read more about eugenics, anthropology, medicine, and the Holocaust in this United States Holocaust Memorial Museum online exhibition.

Obtaining Specimens for the UCL Anatomy Museum: The Anatomist’s Story

Museum Studies students at UCL complete a practical placement in a museum as part of their degree. As objects were off limits in 2020/21 our student placements this year were all about our digitised archives. Archival material has a reputation for being a little dull, but it is often the source of the most fascinating insights into our collections. Nicky Stitchman’s project tracked the development of the museums at UCL from 1826 to 1926 using the UCL calendars and committee meeting minutes.

When students visit the UCL Pathology Museum at the Royal Free Hospital we often discuss the ethics of keeping and using specimens of human remains for teaching and study. Nicky’s research demonstrates that this was not always a matter of concern in medical teaching. In 1854 the rules of University College Hospital stated that

“No specimens of disease removed from patients, or from persons who may die in the Hospital, may be taken from the Hospital until after consultation with the Curator of the Museum of the College, for the purpose of determining whether such specimens shall be preserved in the Museum of Anatomy.”

And it was the duty of Physicians’ Assistants and House-Surgeons

“To deliver to the Curator of the Museum of Anatomy of the College according to Regulation § 54, all specimens of disease removed from patients, whether living or deceased, in their respective departments, and to give him previous notice of all post-mortem examinations.”

So, doctors had to inform Professor Sharpey (the Curator of the Anatomy Museum) whenever they did a post-mortem just in case he wanted any specimens for the museum. No mention is made of patient consent or the ethics of displaying the dead.

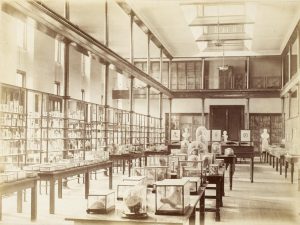

UCL Anatomy Museum when Professor Sharpey was the curator. Image courtesy of UCL Special Collections, ref: UCLCA/7

These days the UCL Pathology Museum no longer actively collects human remains, and institutions that do so have to adhere to the rules of the Human Tissue Authority, obtaining informed, written, witnessed consent from patients.

You can read more about Nicky’s discoveries in this blog where she shows a little love for Assistant Curators, the unsung heroes of the UCL Museums.

Phrenological Head Cast: The Highwayman’s Story

UCL is home to a truly remarkable collection of heads. These life and death masks were collected by Phrenologist Robert Noel in the 19th century to explore ideas of genius and criminality. Phrenology is the long-disproven idea that the shape of someone’s head reflects their intelligence and personality. It is fair to say that Robert Noel’s collection tells us at least as much about Victorian theories of race, class, gender, crime, and mental health as it does about the personalities of his subjects.

Bachelor of Arts and Sciences student Iris Perigaud-Grunfeld wrote her Object Lessons project on head number 41, Babinsky the highwayman. Robert Noel was convinced that Babinsky was a Robin Hood character who stole for good but misguided reasons, and concluded that his head was not of the ‘criminal type’. This cast was taken from life in Prague in 1845 when Babinsky was in prison for robbery. Later Babinsky was released for good behaviour and became a gardener at a monastery.

Iris’ research uncovered details that Robert Noel had missed, and filled in the gaps about what happened after Babinsky died. After his release from prison notorious highwayman Vaçlav Babinsky became a genuine folk hero in Bohemia and Germany, with songs and novels written about him. He even featured in a Czech TV show, and recently Radio Prague International produced an English language podcast about his life which is well worth a listen.

Knowing Babinsky’s full name has also allowed us to find out more about his crimes. He was convicted of attacking a government official, and there is some suggestion that this charge was for biting the town mayor, which makes for a suitably colourful episode in the life of a famous highwayman. However, he was also convicted of at least 2 violent robberies and involvement in a murder, which shows our folk hero in a very different light. Would Robert Noel have interpreted Babinsky’s head differently if Babinsky had been executed for his crimes and never had the chance to turn his life around?

Whether our students next year are working with objects in person, or if they are working with digitised archives, I cannot wait to see what they uncover in the collections.

Close

Close