On the Origin of Our Specimens: The Watson Years

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 20 March 2014

The collection of specimens, known since 1997 as the Grant Museum of Zoology, was started in 1827 by Robert E. Grant. Grant was the first professor of zoology at UCL when it opened, then called the University of London, and he stayed in post until his death in 1874. The collections have seen a total of 13 academics in the lineage of collections care throughout the 187 year history of the Grant Museum, from Robert E. Grant himself, through to our current Curator Mark Carnall.

Both Grant and many of his successors have expanded the collections according to their own interests, which makes for a fascinating historical account of the development of the Museums’ collections. This mini-series will look at each of The Thirteen in turn, starting with Grant himself, and giving examples where possible, of specimens that can be traced back to their time at UCL. Previous editions can be found here.

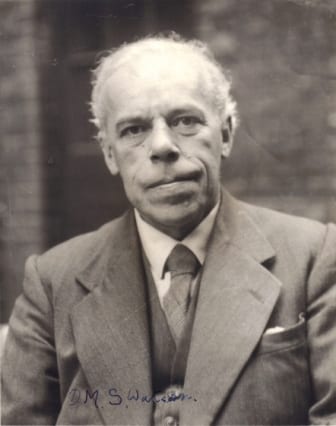

Number Seven: David Meredith Seares Watson (1921-1948)

Number Seven: David Meredith Seares Watson (1921-1948)

D.M.S. Watson, after whom UCL’s science library is named, was born in 1886 in Lancashire. After private tutoring to the age of 14, Watson attended Manchester Grammar School from 1900 to 1904. Watson stayed in Manchester to go to university, where he began by studying chemistry and thus following in his father’s footsteps. However, after advice from his tutor Professor Boyd Dawkins, Watson switched to geology and graduated in 1907 with a first class degree. From the time of his undergraduate degree to 1911, Watson carried out research on aspects of both palaeobotany and vertebrate palaeontology, specifically fossil reptiles. In 1911, Watson was invited by UCL’s then Chair of Zoology, J.P.Hill, to become a palaeontology lecturer at UCL. During this time he studied the embryological development of platypus skulls. During the period in which Watson gave lectures at UCL, he also embarked on fieldwork in South Africa, worked at the British Museum, and spent time ‘visiting numerous German Museums’ (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk)

.

After a five year stint in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, followed by the Royal Air Force, Watson finally returned to UCL in 1920. The aforementioned J.P.Hill retired from the post of Chair of Zoology and handed the reigns over to Watson. In taking up the position, Watson also inherited the teaching collections that now form the Grant Museum of Zoology, and became the 6th successor to Robert E. Grant. As Chair of Zoology, Watson developed the Zoology Department at UCL. He became an eminent palaeontologist and palaeobotanist and his international reputation proved a lure for many researchers who came to UCL, including G.P. Wells and J.B.S. Haldane. As Chair of Zoology, Watson ensured that the embryology research started by previous Chair of Zoology J.P.Hill, was continued, and was the second longest serving carer of the collections after Grant, with 27 years of service before his retirement. Watson retired from UCL with numerous medals, honours and accolades including the Lyell Medal, the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society of London, the Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London and the Darwin Medal. Even after retirement, Watson remained at UCL, writing papers on fossil plants and various aspects of vertebrate palaeontology, until he finally hung up his lab coat once and for all in 1965.

After a five year stint in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, followed by the Royal Air Force, Watson finally returned to UCL in 1920. The aforementioned J.P.Hill retired from the post of Chair of Zoology and handed the reigns over to Watson. In taking up the position, Watson also inherited the teaching collections that now form the Grant Museum of Zoology, and became the 6th successor to Robert E. Grant. As Chair of Zoology, Watson developed the Zoology Department at UCL. He became an eminent palaeontologist and palaeobotanist and his international reputation proved a lure for many researchers who came to UCL, including G.P. Wells and J.B.S. Haldane. As Chair of Zoology, Watson ensured that the embryology research started by previous Chair of Zoology J.P.Hill, was continued, and was the second longest serving carer of the collections after Grant, with 27 years of service before his retirement. Watson retired from UCL with numerous medals, honours and accolades including the Lyell Medal, the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society of London, the Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London and the Darwin Medal. Even after retirement, Watson remained at UCL, writing papers on fossil plants and various aspects of vertebrate palaeontology, until he finally hung up his lab coat once and for all in 1965.

The specimen that started this entire blog series was the platypus skull LDUCZ-Z715, shown here on the right. The original label that accompanies the specimen says “Shot. Prof. DMS Watson. 192a. Papaine technique [sic]”. This presumably means that the platypus was shot, though not necessarily by Watson. The papain technique is a method used to prevent specimen deterioration, though given this is skeletal material, it is unclear how this technique is connected to the specimen as it is now. On the other side the label says “Ornithorhynchus anatinus. Skull and LJ [lower jaw]. Do not remove from case- Valuable and fragile”, demonstrating its historical importance to the collection.

The specimen that started this entire blog series was the platypus skull LDUCZ-Z715, shown here on the right. The original label that accompanies the specimen says “Shot. Prof. DMS Watson. 192a. Papaine technique [sic]”. This presumably means that the platypus was shot, though not necessarily by Watson. The papain technique is a method used to prevent specimen deterioration, though given this is skeletal material, it is unclear how this technique is connected to the specimen as it is now. On the other side the label says “Ornithorhynchus anatinus. Skull and LJ [lower jaw]. Do not remove from case- Valuable and fragile”, demonstrating its historical importance to the collection.

A second specimen that has a relation to Watson is a cast of the fossil amphibian Amphibamus grandiceps. The original specimen label says “Miobatrachus romeri skeleton, in counterpart from Mazon Creek, Will County, Illinois” and mentions that it was described and figured by Watson in 1941, in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. However, whether Watson carried out his research on the original specimen, or on the cast held at the Museum, which is where he was based, is not known for sure.

A second specimen that has a relation to Watson is a cast of the fossil amphibian Amphibamus grandiceps. The original specimen label says “Miobatrachus romeri skeleton, in counterpart from Mazon Creek, Will County, Illinois” and mentions that it was described and figured by Watson in 1941, in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. However, whether Watson carried out his research on the original specimen, or on the cast held at the Museum, which is where he was based, is not known for sure.

Throughout his career, Watson published heavily on fossil fish. He added a large number of fish fossils to the collection at UCL from around the world, though with particular emphasis on Scottish fossil fish localities. Some of the collection he acquired is still at the Grant Museum and many of our Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month blog posts feature specimens from Watson’s collection, or species that Watson had researched and published literature on.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

[UPDATE: Whilst researching this blog series, it was discovered that there had been an extra curator for a few months, following Roy Mahoney. As such, The Twelve became The Thirteen. As the aim of this series is to serve as a permanent record of our history, this and all subsequent blogs have been updated to reflect this exciting discovery.]

6 Responses to “On the Origin of Our Specimens: The Watson Years”

- 1

-

2

Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month: April 2014 | UCL UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 13 November 2014:

[…] Lastly, interesting to note is that these fish were first described by former Grant Museum curator D.M.S Watson in 1934 whilst he was here at UCL. Maybe this was one of the fossils he was looking at when he […]

-

3

Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month: January 2015 | UCL UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 30 January 2015:

[…] Survey, ‘Cambridge University Zoology Department’ and numbers associated with D.M.S Watson, former curator of the Grant Museum and palaeoichthologist […]

-

4

Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month: July 2015 | UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 21 August 2015:

[…] According to the label for this specimen, this is one of D.M.S Watson’s fossil fish. D.M.S Watson was a former curator of the Grant Museum and somewhat of a fossil fishologist extraordinaire. This specimen is […]

-

5

Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month: February 2016 | UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 26 February 2016:

[…] in 1958 in a special volume, Studies on Fossil Vertebrates, which was presented to our old friend D.M.S Watson who collected many of the specimens featured in this series. Given that Watson stole would borrow […]

-

6

Specimen of the Week 232: Holzmaden Fossil Fish | UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 25 March 2016:

[…] By 1936 Bernhard Hauff founded the Urwelt-Museum Hauff in Holzmaden which (to this day) showcases many spectacular fossils found in the region prepared by the Hauff family. Just prior to this, Herr Hauff gave this Dapedium specimen to the Grant Museum’s curator at the time (and fossil fish authority) D. M. S. Watson : […]

Close

Close

[…] was a technician at UCL for around a year, at which time D.M.S.Watson was Chair of Zoology and in charge of the collections that now constitute the Grant Museum. Harris […]