Flinders Petrie: An Adventure in Transcription

By Rachael Sparks, on 3 September 2013

Flinders Petrie began his autobiography by warning that “The affairs of a private person are seldom pertinent to the interests of others” [1]. Fortunately for both us and his publisher this proved no impediment, and Petrie went on to write about himself, his thoughts and his life’s work at great length.

Petrie was a prolific writer, both in the public and private arena, and we are not short of material to help us learn about his life. But not everything he wrote was wordy. I’d like to introduce you today to a more unexpected side of his penmanship: his personal appointment diaries.

Now part of the archives of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, These little 8 x 15cm books are known generally as Petrie’s pocket diaries, and entries are varied and brief. We hear about his health (‘diarrhoea’), the weather (‘rain’, ‘gale’ and ‘hail storms’), and its impact on his digging progress (‘Men off’). We hear about his own activities (‘planning’, ‘writing’, ‘photographing’, and the classic ‘finished all doings’), and those of his associates.

Perhaps the best such reference appears on in June 1927 when Petrie opened his London exhibition. This coincided with the University College’s centenary celebrations, which led to a royal visit. Or as Petrie puts it, ‘King + Queen in’.

The diaries can be surprisingly personal and intimate. You can just imagine Petrie pulling out a stub of a pencil, and scribbling down a short reminder to himself of what he had done that day. But what did Petrie think about his hasty jottings? Did he understand their future significance? Could he have ever guessed that they might one day find their way into a museum? And how would he have felt about that?

Here is a sample page from Petrie’s pocket diary for 1926/1927, the year he went to excavate at Tell Jemmeh in British Mandate Palestine.

The first thing you notice is how the dates of the diary have been changed by hand. For Petrie, the standard year did not run from January to December; it began when he went into the field.

So rather than burden himself with two lightweight, miniscule diaries, Petrie frugally purchased one copy of next year’s diary before he left England. He would start using the end of the diary straight away, overwriting the printed dates. Come the new year, he would go back to the beginning and synchronise with the printed version.

Petrie was nothing if not an original.

I had my first stab at transcribing these diaries several years ago, when my levels of ignorance were outstripped only by my enthusiasm. This time round I’ve acquired a much better understanding of the historic setting of Petrie’s work. Even so, there are times when I find myself at a standstill, as the laconic combines with the obscure to create the unintelligible.

Take this entry. Petrie arrives in Marseille, goes to a squiggle squiggle, then on to the ‘Champollion’. What’s to be made of entries like this?

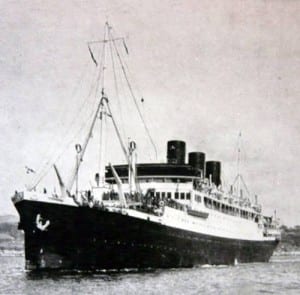

Knowing Marseille was a port, I suspected Champollion might be a ship. It was. The SS Champollion covered the route between Marseilles, Alexandria and Beirut. This led to the discovery that Squiggle squiggle was not spirit writing after all, but the phrase ‘Messageries Office’, that is, the offices of the company that ran this line, Messageries Maritimes. So here we have Petrie popping in to check the details of his passage the day before he was due to sail. Piece of cake!

The SS Champollion. A fine figure of a ship. Image courtesy of Syldauphine (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CHAMPOLLION.jpg, accessed on 14 Aug 2013).

The diaries are great for recording the rhythm of dig life and the sorts of activities Petrie engaged in. We learn of the role played by the elements and interruptions caused by site visitations as archaeologists descended in scholarly packs. What we don’t hear about is Petrie’s leisure time. We know that his workers were given a day of rest on Fridays, the Muslim Sabbath, but there is no sign that Petrie allowed himself a similar respite (or if he did, he did not think it interesting enough to record).

Indeed, many of his Fridays seem to be spent planning and taking level readings on the tell, no doubt because this gave him a chance to work unencumbered by the usual hubbub of the dig. But then we do know that Petrie didn’t really do holidays very well; to him there was no such concept as Le Weekend.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptology digitised Petrie’s pocket diaries in 2012 [2]; they now hope to transcribe the contents and put this material online [3]. I can’t wait to see the rest of them. So watch this space, and be prepared to share in my amazement, astonishment and not infrequent bewilderment.

Rachael Sparks is Keeper of the Institute of Archaeology Collections, which include an important selection of material from Petrie’s excavations in British Mandate Palestine.

___________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Flinders Petrie. 1930. Seventy Years in Archaeology, p. 1.

[2] Digitisation was carried out by Paolo Del Vesco and Kristin Phelps. Paolo has subsequently been engaged in researching this material, and will be shortly publishing a paper on his work, called Day after day with Flinders Petrie, which was first presented in the conference Talking along the Nile. Check it out. It’s a cracking good read, and I wish I’d written it myself.

[3] I’d like to thank Alice Stevenson for allowing me to contribute to this project, and for permission to reproduce the diary images used in this post, all of which were sourced from Pocket Diary PMA/WFP1 115/9/1 (47), which covers the period from 14th November 1926 to 11th November 1927.

Close

Close