Museum life, loves and labels

By Subhadra Das, on 18 February 2014

Having spent some time digging around, I’d like to share with you some of my thought processes to build up a picture of the development of the Galton Collection through its object labels.

Nothing is so helpful to a curator than the work of those others who have worked to document the collection before them. In the Galton Collection, some of this consists of labels attached to objects. As previous blog authors have said, old object labels can help us to work out the provenance of objects in the absence of this information in a complete catalogue.

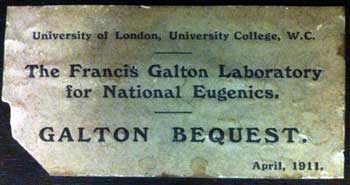

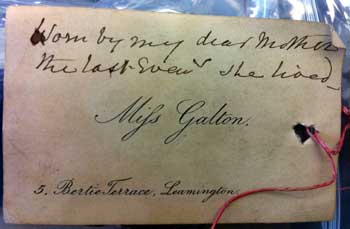

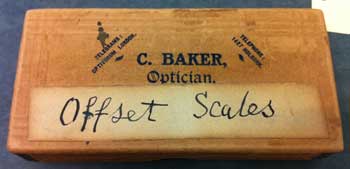

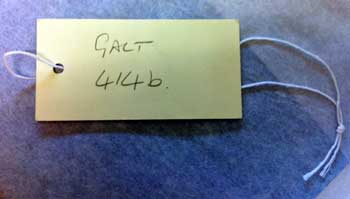

For example, objects with this label:

can safely be dated to the original bequest of Galton’s personal effects to UCL on his death in 1911. This is a crucial thing to demonstrate because the collection has only been managed to museum standards relatively recently. For most of the 20th century, it existed as a departmental collection at the Galton Laboratory, and various anthropometric devices were added over the years as they became obsolete. As you can see from the state of this label, it’s a lucky survivor, and not every object which was part of the Bequest retains this label. This is why whenever I am asked if an object is an authentic, that is, it was used by Galton, I will inevitably dither and tell them this long story.

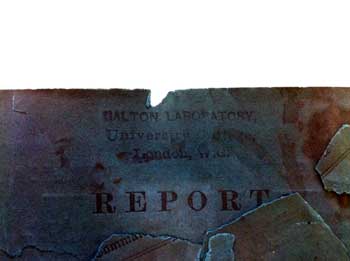

The Laboratory had its own stamp too:

And this might indicate Galton-related object they acquired after the original bequest.

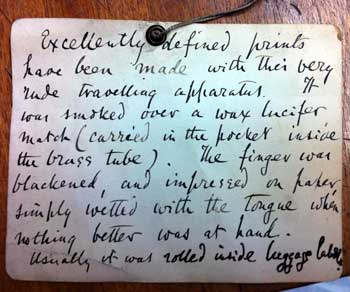

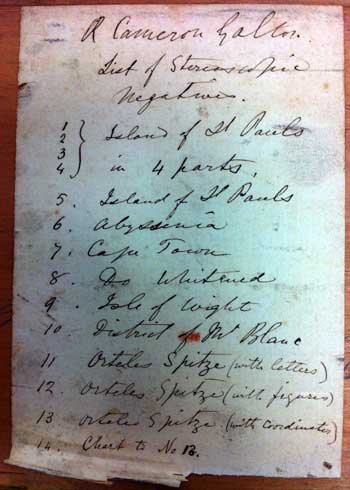

This is one of my favourite labels:

because it was written by Galton himself and it explains the purpose of what would otherwise been a very random mystery object (a metal tube mounted on a wooden handle, the whole thing about the size of my middle finger) whose use would not have been documented anywhere else.

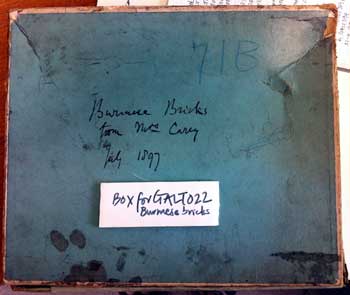

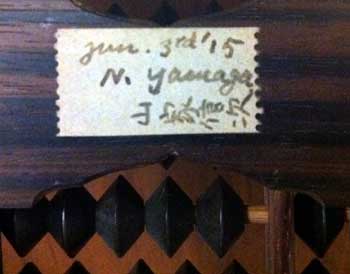

A superlative label this one

because it not only describes the objects but also the name of the person who sent them and the date this was done. There is also room for speculation – how were these previously ’80’ and now ’71B’? Does this blue pencil numbering system relate to the ink label? Note also, my somewhat redundant label of a label.

This is a very poignant label

which renders an otherwise mundane object – a black fabric belt with a jet buckle – into a treasured memento of a loved and now departed parent. The story has the potential for further sadness because we don’t currently know if the belt was sent to Galton by his sister on their mother’s death, or if she kept it and he received or retrieved it after she died.

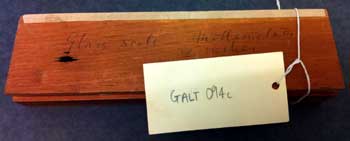

Normally it is frowned upon to scribble a label in pencil all over an object, as in this case

But in this case, the inscription is historic, so that’s OK. The staying power of pencil is consistently under-reported. Someone once told me that Charles Darwin wrote all his field notes during his voyages around the world in pencil. Back in England he went over the writing in ink to make it more permanent, although the caustic nature of ink he used had the opposite effect. I have no idea if this is true, but it makes for a good label-related story.

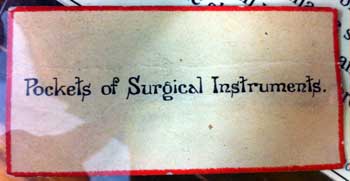

Some labels have a gift for stating the obvious:

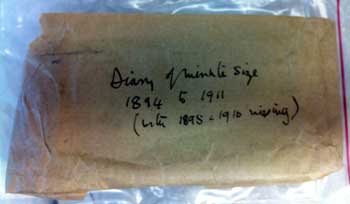

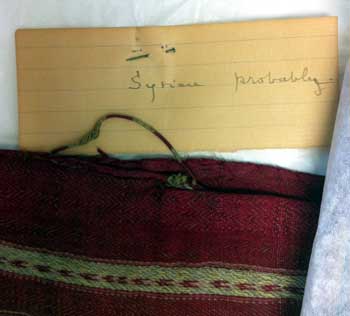

And others don’t:

I do like a person who knows their own mind.

Great. Now all I need to do is find out what a pantagraph is.

And, while we’re on the subject…

…how’s your Japanese?

This is a surprisingly unhelpful label given the level of detail.

While it does describe the contents of the box, it doesn’t tell you what the images actually show, or how they were intended to be used. Luckily for us, a researcher is looking in to this set of objects and has found out lots of fascinating things about them. Watch this space for more details later.

Then there are objects with

SO MANY LABELS! The original plaque, the Bequest sticker (also inscribed D60 and with another number scratched out), the accession number, and a mystery ‘119’. If we ever find the original registers, if those ever existed in the first place, we’d be set.

The story of the Galton Collections labels carries on into the modern day:

There is nothing like a white label inscribed with bright orange felt tip pen and stuck directly on to a historic object to strike fear into the hearts of museum conservators.

Then there are the accession labels. In the mid-2000s a Heritage Lottery Grant paid for a collections officer to document the whole collection. She did a stellar job and now every object has a label that looks like this

And an entry on the object database to match. Which is excellent. And you may wonder why it is I have taken another picture of what appears to be the exactly same type of label:

Do I have a tendency to overkill?

I do, as it happens, but no, my friends, that is not the case here. The reason the second image is required is because the second label is written in different handwriting.

It is that level of attention to the small details that is not only why they pay me the big money, but also the reason why, one of these days, we will know the whole story of the Galton Collection and how it came to be.

2 Responses to “Museum life, loves and labels”

- 1

Close

Close

Handwriting is so useful to the curator: so think what an impact doing everything on databases is having on our future accountability. With data being constantly updated and overwritten, its so difficult now to find out who thought what about an object, and when. Viva la paperwork!