Grant Museum Objects on Tour: Lost Labels

By Mark Carnall, on 1 August 2013

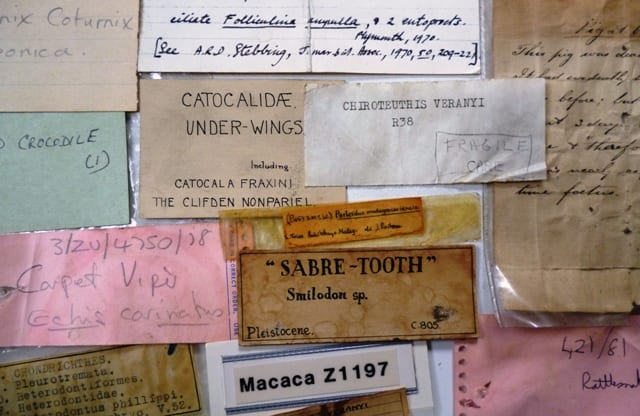

Last week, the exhibition Nature Reserves opened at GV Art, London a group exhibition examining the relationship between how humans interpret and archive the natural environment. Tom Jeffreys, the curator of the show, contacted the Grant Museum to discuss some ideas about how natural history museums archive and organise specimens and these discussions lead to us lending a collection of orphaned labels, that cause me great personal anguish whenever I have to add to this sub collection, to the show.

As I mentioned in a previous blog post in order for our specimens to be of the most possible use in scientific research, we want to know everything about a specimen. We want to know everything about the animal: exactly where it lived (down to a GPS reference), how it died, who collected it, what was it doing when it was collected, who prepared it, how was it prepared, why was it collected, who identified it and how it was imported/exported. With all this information (and more) the specimen will be of much greater use in scientific research.

Unfortunately, for collections like the Grant Museum, because it began as a teaching collection in the 19th Century a lot of this information wasn’t considered as important as it is today. That’s not to say that this information wasn’t collected at all but it’s tied up in the archives, scrawled on paper notes and in some cases written on the surfaces of specimens. Part of my job here is to try to reconnect as much of that information as possible with the relevant specimens.

These days there are very robust guidelines on how to keep information associated with objects. Specimens should be permanently marked with a unique reference number (which we refer to as the accession number), we record as much information as possible from the depositor about any objects being donated to the museum and all of this information is recorded in an indexed object catalogue and corresponding paper records. However, the collection has existed for many years previous to these modern standards and bringing older collection information up to current standards is referred to as ‘the backlog’.

There have been a number of attempts to catalogue the museum, the first was a publication created by E.Ray Lankester at the end of the 19th Century, so already there was nearly 80 years of information that went unrecorded. Unfortunately, this catalogue seems to be half a catalogue, half wishlist and it isn’t clear if some of the objects were ever in the collection. After this there was a card index system, then another card index system in the 1980s followed by electronic systems which we use today. Unfortunately, each of these sources of information, not to mention the thousands of letters, labels, notes, inventories, historic photographs and article reprints, doesn’t perfectly overlap with each other so when we’re answering research queries we have to check all of these sources to be 100% sure we’ve not missed a useful specimen. That is, until, the entire collection is completely documented, something that won’t happen within my life time and something that I don’t think a single museum has ever achieved.

One of the biggest problems, as with this collection of labels that have become disassociated with objects, is how we reconcile information with specimens especially when there’s any doubt. If we’re not careful, we could end up associating orphaned information with the wrong object for the rest of time. As an example we may physically have ten frog skulls and ten frog skulls listed in our electronic catalogue, however, the ten records might refer to frog skulls that have been lost, transferred to another institution, or which haven’t currently been located. Some of those skulls (this is often the case unfortunately) may have been recorded twice creating duplicate or ‘ghost’ records. But we can’t just delete records we can’t match to specimens as they might actually be the only reference to an object that is currently missing. Some of these records may have key information with them and we’d want to be 100% sure it goes with the correct specimen otherwise we might be mixing up information and polluting data pools. It’s enough to drive a curator mad. And it does. Frequently.

Another important reason for matching information, particularly lost labels, is that the style and other inferred tidbits can often be the only way we can secondarily infer an age or provenance of an object. The Grant Museum is very much a museum of museums, we hold the collections from a lot of university departments that closed down their collections, and it is often only from the style of the label, handwriting, number format, position of the label and marginalia that we can work out where the object originally came from. Subsequently we can then attach the information about how and why it came to UCL and put lower limits on the age of the specimen i.e. this object is at least as old as 1980 when collection X was donated to the Grant Museum. These discussions are what piqued the interest of the exhibition curator Tom Jeffreys and this is why the contents of our “Lost Labels” box is now on display in Nature Reserves.

This is something that all museum curators have to contend with but I thought this brief insight into the challenges with working with historic objects is a bit of a glimpse behind the scenes into the working life of a museum. The orphaned labels look fantastic at GV Art Gallery as well as the other works in the exhibition. Nature Reserves runs at GV Art, London until the 13th of September.

Mark Carnall is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

3 Responses to “Grant Museum Objects on Tour: Lost Labels”

- 1

-

2

Museum life, loves and labels | UCL UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 18 February 2014:

[…] Collection, some of this consists of labels attached to objects. As previous blog authors have said, old object labels can help us to work out the provenance of objects in the absence of this […]

-

3

Documenting Cephalopods Part 3 Labels, labels, labels | Fistful Of Cinctans wrote on 24 November 2017:

[…] in the exhibition Knowledge in Motion at UCL and loaned to exhibition Nature Reserves at GV Art Gallery both exhibitions examining knowledge production and […]

Close

Close

Great post – I really like the term “orphaned labels”.