The Press Photography of Red Vienna 1929 – 1938: An interview

By ucwchrc, on 8 November 2013

Helen Cobby interviews the researchers of the Red Vienna project, Eva Branscome and Catalina Mejia, before their Pop-Up Display and Lecture on Tuesday 12th November.

This photo is a wire photo: It shows the Nazis using the Karl-Marx-Hof as a politically laden backdrop to their feeding station for the starving Viennese

This event is based round American press photographs depicting social housing estates during the turbulent inter-war years in Vienna. The photographs record three specific epochs within this time frame, from the building of the social houses to the take-over of Austria by the Nazis. The interview below includes Eva’s and Catalina’s thoughts about the development of their project, the active role of the photographs in the manipulation of historical events, as well as the importance of new photographic technologies emerging at the time and new relations between image and caption that this brings.

Eva Branscome is a PhD candidate in Architectural History and Theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL. She currently teaches Architecture in the UCL History of Art Department. Her research investigates the art and architecture of the post-war avant-garde scene in Vienna, looking especially at cross-cultural influences and media involvement.

Catalina Mejia studied for her Masters in Architectural History at the UCL Bartlett School of Architecture, and is now a PhD candidate in Architectural Theory and Criticism at the University of Newcastle, where she also teaches. Her research deals with questions of photography and repetition in architectural criticism as well as the relationships between word and image.

How would you summarise some of the fundamental debates posed by these press photographs? And what social constructions do you think the photographs specifically add to, or help create?

Eva: The first lot of photographs I have document the fantastic socialist housing projects that took place in Vienna at the end of the 1920s. The government realised it had a problem with overcrowding and people being homeless after the First World War. These housing projects addressed issues with families, and with children – such as not having a place to play, and being forced into crime. It was believed that by giving families decent homes, society could be changed and people could be made happier and more productive. These housing projects produced great excitement internationally by experimenting with Socialism through architecture and thinking about how it could change the world.

The Vienna housing projects were happening on a massive scale, for example the famous Karl Marx Hof could accommodate 5,000 people. The spaces were created round a courtyard and had facilities for playing, hanging out washing, and even going to the cinemas – so it was not just decanting people. This courtyard structure meant that there were spaces mediating between public and private because what used to go on in the street would now go on in the courtyard. So there was social control created through this setting.

Then the second group of photographs I was sent tell a completely different story. Their captions are full of bloody descriptions. Photographers are obviously standing a large distance away from the buildings where fighting and shooting was breaking out during the Socialist uprising against the fascist dictatorship of Engelbert Dollfuss in 1934.

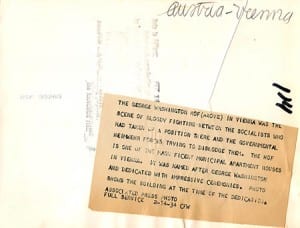

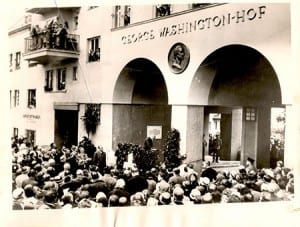

This is the back of the photo showing the opening celebration of the George-Washington-Hof: It was actually used during the Socialist uprising in 1934 in which the municipal housing blocks became fortresses of the resistance. The press release pasted to the back acknowledges this

The last photograph shows the Karl Marx Hof buildings as the background to a large crowd in which there are no women – only men who are pushing to get food being handed out by Nazis after Austria was annexed by Germany in 1938. This is obviously a propaganda drive. But all of these photographs were taken for a certain agenda, using the buildings as a stage for this.

How did you find these images? Did they speak to you straight away?

Eva: This project began when I needed to find some good quality images of Red Vienna to illustrate some of my PhD powerpoint presentations. I was covering the post-war history of Vienna in my PhD, so the photographs were just needed for background context. I was also focusing on architecture but when I saw these photographs they were immediately interesting as objects and artefacts in their own right. They are tactile and have many markings on them, such as the date of the press release, when they where traded, and the stamp of when then arrived.

The objects were intriguing in their own right and telling a very interesting story about how media was used to create history and also how the snowballing political developments in Vienna perpetuated changes within photography and its transferral, so I asked Catalina to be part of this research project. Her PhD research centres on architectural photography and the word-image relationship, and she agreed.

What is the relationship between the captions and the photographs?

Catalina: It is different when thinking about a press photograph that was sent overseas by airplane compared to a wire photo. It may not be evident but they are easy to recognise. You can differentiate them by the image colour and definition quality and by the captions and other written or stamped information they hold. The wire photographs are unique for the way that their captions are within the image itself. In the other set of photographs, the typed caption was attached to their backs. In both, the captions are as fundamental as the event depicted. Both are press photographs, which is different for other scenarios where the caption is subsidiary. Press photographs, as graphic journalism, always have their specific audience in mind. It is this distinct word-image relationship that conveys a particular meaning.

So there are different types of photographs in the collection you have acquired?

Catalina: There are two different types. ‘Paper’ photographs and wire photos. In this case both are evidence of period that saw a big change in journalism photography. At first, photographs were processed in dark rooms and sent from Europe over to North America. This could take about two-weeks. So this was not immediate news. However, in the 1920’s Vienna started to become a place on the threshold of revolution. It was continuously the focus of international news, so people were watching Vienna fearfully and wanting immediate updates in case there was a domino effect in other countries. This coincided with the creation of the wire photograph in 1935 in the US; technology that triggered the possibility of immediate news.

Eva: Catalina will show a short film made in the 1930s about how wire photography works during the talk next week. It is the first type of scan, like a fax, which was sent by telephone cable. This way, it arrived with the news, so text and image were linked, unlike the earlier photographs.

Catalina: These wire photographs were originally taken in Europe and sent by wire to America, whereas in the case of the ‘paper’ photograph most likely the negative would have remained in Austria or Vienna, and the photograph sent by airplane, or by sea. One of the things that wire technology allowed was to send many more photographs in less time.

Before wire photographs, the images would be retouched before being sent, whereas with wire photos, you receive a photo and then manual retouching comes afterwards. This retouching was ideological. For example, in the photograph of Nazis handing out rations, the tin containers with which people collected food and the Nazis are retouched, maybe even a little moustache added, but the common people are left white washed. This shows how the retouching was part of storytelling and construction.

Press photographs also allowed stories to be told in a more slanted way; they are not neutral, they can invent things. We think photography is not an exact documentation, and this set of photographs shows this is. Also the use of architecture here is not neutral either. Part of our aims with this exhibition is to illustrate how the materiality of these press photographs is important for the construction of the situation of Vienna, and as a tool for journalism and architecture.

What do you think the anonymity of the photographs and photographers adds to the project?

Eva: The anonymous nature is crucial to the project. It was also our biggest challenge because we don’t know who took the photographs, and we don’t know who wrote the press release either. But it has been much easier to find out information about the journalists rather than the photographers. The photographers remain anonymous.

Catalina: It was also common for the time period that there aren’t even the usual stamps on the back where the photographers were credited for the photographs produced in the dark room with a professional camera.

This anonymity is a big shift from how we treat photographs today: The authorship is crucial in terms of the use of photographs in publications and recent scholarship focuses on who is the photographer as an artist. Copyright of images is a very big topic today. But it appears that this was not important at the time. The photographs were bought by an agency and stamped by it and not the photographer; rights and credits followed the object.

What were some of the challenges of the project?

Eva: One challenge was thinking how to display the photographs at the exhibition and allow for both the image on one side and the caption on the other side of the paper to be seen. We have decided to display them in between sheets of perspex on easels so people can turn them around. We might even just show the backs to begin with. They are really beautiful just as objects and tell so may interesting stories, but we were also worried about doing the exhibition without knowing anything about the conditions and circumstances in which they were produced.

What were the highlights?

Eva: We kept researching and finding new leads. Only a few weeks ago I finally found a journalist’s memoir that mentions one of the photographer’s names who sold the Anglo-American journalists his photographs. We never knew these photographs would open up all these questions and this has definitely been a highlight. It was fascinating to discover one story after another and how they linked up with history making through looking at pictures of architecture.

It was also satisfying that the project emphasises that you cannot separate architecture from the politics, histories and power structures – it is linked with society and is a social production. Therefore our project is very interdisciplinary. This notion of architecture is something that was also expressed by my tutor, Professor Adrian Forty. He was also Catalina’s tutor for her Master’s Degree at the Bartlett. He has definitely influenced how we understand architecture and his thinking should also be credited for this project.

Catalina: For me, the wire photograph was new – and this was a definitely a highlight as it relates the socio political with the technological context, while at the same time questions the context of journalism at the time.

Where do you see your project going next?

Eva: In the last phase, we will try to find the actual newspapers from the time and hopefully discover which photographs were finally used. Getting to know the context of their publication is crucial, so we want to close the loop. It will be interesting to see how this changes or impacts upon the information we have already found.

Eva and Catalina’s Red Vienna Pop-Up Display and Lecture is on Tuesday 12th November from 1 – 2pm at the UCL Art Museum

Helen Cobby is a volunteer at UCL Art Museum and is studying an MA in The History of Art at UCL.

One Response to “The Press Photography of Red Vienna 1929 – 1938: An interview”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] on the UCL Art Museum Blog: Helen Cobby interviews the researchers of the Red Vienna project, Eva Branscome and Catalina […]