Museums Showoff: Celebrating the mundane

By Mark Carnall, on 18 October 2013

Earlier this week I was lucky(?) enough to have a spot on the excellent Museum Mile Museums Showoff special as part of the Bloomsbury Festival. For those of you who don’t know, Museums Showoff is a series of informal open-mic events where museum professionals have nine minutes to show off amazing discoveries, their research or just to vent steam to an audience of museum workers and museum goers. My nine minutes were about the 99% of objects that form museum collections but you won’t see on display. They fill drawers, cupboards, rooms and whole warehouses. But why do we have all this stuff? Who is it for? In my skit on Tuesday I only had nine minutes but I thought I’d take the time to expand on the 99% and the problem of too much stuff (particularly in natural history museums) and what we can do with it.

Tip of the Iceberg

Museums often display only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to collections. Here at the Grant Museum we have about 7% of the collection on display and it tends to be the Hollywood Animals that make the cut. At larger museums it can be less than 0.1% of the collection that makes up the public facing galleries. In my relatively short career as a museum professional I’ve been very fortunate to see behind the scenes in more museums than most and boy, there is a lot of stuff. Even though I love natural history and am very passionate about museums and the future of the museum sector sometimes I do wonder why do we have all this stuff?

In natural history, the obvious and often made, argument is that our collections can tell us about global challenges that affect us all including climate change, organisms that cause or spread human diseases, extinction, agriculture and aquaculture and from geology the exploitation of fossil fuels. Natural history collections are the only record of life on Earth and if we are to make any models or predictions we need to dip into the data enshrined in objects.

However, there are large portions of natural history collections which could never contribute to those agendas. All the ‘Raggy Doll‘ specimens without data for example. All those specimens that require four text books of explanation. Most fossil specimens can be used to reconstruct the past with only limited impact on what’s happening in the present. There are rooms and rooms full of bad taxidermy and taxidermy dioramas that for reasons of taste, health and safety and changing scientific ideas never see the light of day. Even something as simple as an animal not having a common name (to put on a label) can keep a specimen off display There are large chunks of the animal world which simply aren’t being actively studied (for now). Lastly there are all the models, casts and those dreaded boxes.

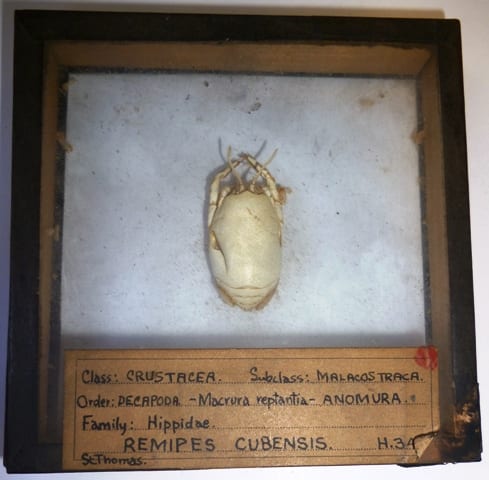

Spare a thought for specimens like this. Dusty, pest attacked, wrongly named crabs. SAD SMILEY FACE.

So how do we make the most of the 99% now especially if they aren’t saving the world? Well, in short, it shouldn’t matter how important our specimens are to science. Every specimen has a story to tell.

Museums of Inspiration?

One of the most important, but frustratingly difficult to qualify and quantify, is the power of museums to inspire. Museums of all shapes and sizes provide spaces for unique encounters. I think everyone who works in museums feels strongly about how inspiring they can be, be it inspiring them to work in a museum or to work in zoology or just to inspire them to take an interest in the great wide world. It’s woolly I know but it is an important role and you don’t have to have the world’s biggest, best or brightest specimens to inspire. It’s a well worn trope but it’s the staff not the stuff that can bring collections to life and social media is creating a lot more opportunities to unleash the geeks (you don’t have to be a geek to work here but it helps…) the enthusiasm and personality being more important than the actual esoteric content. Here are some of the ways that natural history museums are fore-fronting the 99%.

Celebrating the mundane

The Micrarium at the Grant Museum of Zoology showing off those problematic and complex and numerous microscope slides

Novel displays and exhibitions are one way. Stored collections tend to be those objects that aren’t aesthetically pleasing, are complex to interpret, incomplete or damaged or represent voluminous but low popular appeal groups (corals, sponges, most crabs, most insects, bryozoa). One of the driving ideas behind our Micrarium and events around the weird and wonderful world of the stores was to make use of otherwise ‘unusable’ collections.

Social media is a great way of exploring those esoteric specimens. Our underwhelming fossil fish of the month and the recent count down to our specimen of the week 100 focus on the specimens you won’t normally find on display and those animals which aren’t already A-listers. But sometimes we don’t know as much about the A-listers as you might expect. As I’ve been finding with writing underwhelming fossil fish of the month even the most uninspiring and ‘unusable’ specimen can be inspiring if framed in the right way (even if that way is to break the format and highlight how uninspiring it is).

Other museums are leading the charge with other ways of engaging with stored collections, store tours are a well established way of demonstrating what it is museums truly are. Recently I was amazed at the Netherlands’ Naturalis museum’s software that gives visitors the chance to contribute to documenting the collections (bypassing the traditional display altogether) really showing exactly the millions of specimens that make up scientific collections.

Collectively, we need to be more creative about the objects that are otherwise of no use and celebrate the objects and specimens that traditionally wouldn’t pass the harsh test to make it onto display. Have you seen any good examples of museums celebrating the mundane? If so, drop them in the comments below.

Mark Carnall is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

5 Responses to “Museums Showoff: Celebrating the mundane”

- 1

-

2

Chris Ruston wrote on 18 October 2013:

Hi, the timing of your article is astonishing, as a friend and I have just spent the morning in our local museum at Southend, looking at the donated “shoebox” collections of birds eggs. While it was explained these are of little interest to scientists as artists we have had a fabulous time studying them from a different point of view. Not only are the objects beautiful in themselves , but we have also been intriugued by the “personal stories” associated with them, for example Mre Tillmans egg collection, presented in an 1950’s shoebox, or a young lads collection in an equally old wooden liquorice all sorts box.

We were so engrossed we did not have time to look at the more formal collections. On the agenda for our next visit. We have learnt a lot already, and hope that we can produce some work which will in some way connect with the issues you raised.

, thank you, Chris. -

3

Matt Whyndham wrote on 21 October 2013:

+1 for the Cabinet of Indifference. There was once a popular Flickr group called Boring Photos. Then dispute raged due to the inherent savour of someone else’s blandness. It eventually wound up, after a twilight of being called There are No Boring Photos.

-

4

Mark Carnall wrote on 22 October 2013:

Daniel and Matt. It’s true to a certain extent that the act of putting something on display in a museum makes anything interesting. Many years ago I was inspired by a series of postcards given away by the Palaeontology Association which were the most bland and unsexy series of images of various fossils. I still have them today.

Chris, great to hear stories from other museums with collections which at first glance might appear to be unusable.

-

5

Home Decratiion wrote on 11 November 2013:

Chris, great to hear stories from other museums with collections which at first glance might appear to be unusable.

Close

Close

Perhaps you could have a “Mundane Corner”, or “Cabinet of Indifference” and cycle these specimens through on a regular basis.