Odus to Sparnodus

By Mark Carnall, on 9 May 2011

This week I’ve been rifling through our stores to dig out fossils for our upcoming installation The Future Took Us. As a consequence I’ve been working with fossil fish called Sparnodus.

Close

Close

News and musings from the UCL Culture team

By Mark Carnall, on 9 May 2011

This week I’ve been rifling through our stores to dig out fossils for our upcoming installation The Future Took Us. As a consequence I’ve been working with fossil fish called Sparnodus.

By Jack Ashby, on 5 May 2011

A delayed account of zoological fieldwork in Australia – Part 14

From April 2010 I spent about five months undertaking several zoological field projects across Australia. I worked with government agencies, universities and NGOs on conservation and ecology studies ranging from Tasmanian devil facial tumour disease, the effect of fire, rain and introduced predators on desert ecology and how to poison cats. This series of blog posts is a delayed account of my time in the field.

Weeks Sixteen to Nineteen – part 3

In the last couple of weeks I’ve been describing the final field project on this trip, joining ecologists from the Australian Wildilfe Conservancy (AWC) on a full faunal survey of their sanctuary on the Arhnem Land Plateau in the Northern Territory. During this one month expedition I encountered more snakes than I had throughout my whole life previously. Snakes on field work is the topic of this week’s post.

By Rachael Sparks, on 3 May 2011

Archaeology sounds so glamorous – well, it’s an ‘ology’, after all, and it’s got an impressively archaic diphthong in it (unless you go for the tragically dull American spelling of the word). The word conjures up images of exotic, far-flung places where on tossing your rugged Akubra hat to one side, you need do no more than lay down a few well-placed trowel strokes before uncovering the long-lost secrets of time itself …. or something of the sort. Those clumsy archaeologists are always stumbling over something. But you know it’s not all Time Team, right? That one moment of instant fame, on discovering something über-cool, comes at the end of a couple of decades of hard slog, discovering many things that seem interesting to you but may not sing to the rest of the universe in quite the same way. To be followed by months of equally hard slog, dealing with all the subsequent work that object generates. Cataloguing it. Researching it. Publishing it. Publicising it. Correcting all the erroneous things that people go on to write about it, because they didn’t pay attention to what you said about it in the first place. And so on.

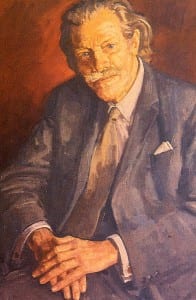

The most visible archaeologists are those that are good at the publicity thing. You may not know who they are, but they and their often impressive facial hair become like old friends in your living room. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who founded the Institute of Archaeology, was a dab hand at dealing with the media. He used to make regular appearances on Animal, Vegetable or Mineral, a TV quiz show in which archaeological experts were asked to identify random objects, to the entertainment of their studio audience. Not only was he a superb archaeologist; he also bore a world-class moustache; a sort of Terry Thomas pantomime villain at its best.

The most visible archaeologists are those that are good at the publicity thing. You may not know who they are, but they and their often impressive facial hair become like old friends in your living room. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who founded the Institute of Archaeology, was a dab hand at dealing with the media. He used to make regular appearances on Animal, Vegetable or Mineral, a TV quiz show in which archaeological experts were asked to identify random objects, to the entertainment of their studio audience. Not only was he a superb archaeologist; he also bore a world-class moustache; a sort of Terry Thomas pantomime villain at its best.