From Archaeological Glamour to Museum Mundanities

By Rachael Sparks, on 3 May 2011

Archaeology sounds so glamorous – well, it’s an ‘ology’, after all, and it’s got an impressively archaic diphthong in it (unless you go for the tragically dull American spelling of the word). The word conjures up images of exotic, far-flung places where on tossing your rugged Akubra hat to one side, you need do no more than lay down a few well-placed trowel strokes before uncovering the long-lost secrets of time itself …. or something of the sort. Those clumsy archaeologists are always stumbling over something. But you know it’s not all Time Team, right? That one moment of instant fame, on discovering something über-cool, comes at the end of a couple of decades of hard slog, discovering many things that seem interesting to you but may not sing to the rest of the universe in quite the same way. To be followed by months of equally hard slog, dealing with all the subsequent work that object generates. Cataloguing it. Researching it. Publishing it. Publicising it. Correcting all the erroneous things that people go on to write about it, because they didn’t pay attention to what you said about it in the first place. And so on.

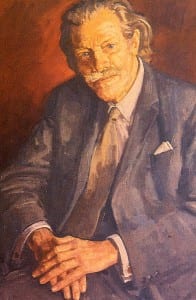

The most visible archaeologists are those that are good at the publicity thing. You may not know who they are, but they and their often impressive facial hair become like old friends in your living room. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who founded the Institute of Archaeology, was a dab hand at dealing with the media. He used to make regular appearances on Animal, Vegetable or Mineral, a TV quiz show in which archaeological experts were asked to identify random objects, to the entertainment of their studio audience. Not only was he a superb archaeologist; he also bore a world-class moustache; a sort of Terry Thomas pantomime villain at its best.

The most visible archaeologists are those that are good at the publicity thing. You may not know who they are, but they and their often impressive facial hair become like old friends in your living room. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who founded the Institute of Archaeology, was a dab hand at dealing with the media. He used to make regular appearances on Animal, Vegetable or Mineral, a TV quiz show in which archaeological experts were asked to identify random objects, to the entertainment of their studio audience. Not only was he a superb archaeologist; he also bore a world-class moustache; a sort of Terry Thomas pantomime villain at its best.

Wheeler’s talent for publicity was not just show; he used it to get things done. It was Wheeler’s perseverance that transformed the Institute of Archaeology from a theoretical idea to an active hub for archaeological training and research. In this, he owed a lot to another hirsute self-publicist, Sir Flinders Petrie, who provided the funds that made the Institute a reality. They came with a catch; Wheeler must also take Petrie’s collection of some 20,000 objects from his excavations in British Mandate Palestine. This was an offer too good to refuse, of course, and so the Institute of Archaeology Collections were born. Over time other donations followed, generated by the fieldwork of Wheeler and many members of staff over the years. As a result, our collections now have a truly worldwide scope, reflecting the developing interests of the Institute itself over its long history.

After the initial fanfare, of course, come the museum mundanities. Once you move beyond the publicity sound bites – Notice us! We’ve got the Rarest This, the Biggest That, the Quirkiest Whatever – you come to the day-to-day business of keeping the beast that is your collection in order. Here we can be thankful that archaeologists have more skills than knowing how to purchase appropriately rugged headgear. Every great discovery is founded on great organisation, and I am grateful for the small bureaucracies of the past on a daily basis. So all hail to Flinders Petrie, Wheeler and others, for insisting that their sherds be marked with their contexts, saving many a misplaced item from an ignominious end in a ‘problem’ box. Such markings have usually outlived the various bags and boxes and labels used to store archaeological finds. Whoever said plastic was non-biodegradable was an idiot; I’ve seen plastic bags reduced to shreds after only a few years in storage. Whereas marked sherds march on forever. Now that’s worth much more than a few minutes of prime time television.

Close

Close