Leonard Darwin – “If I had to write this again I should in Chapt XIII paint a more lurid picture.” His personal copy of ‘What is Eugenics?’

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 10 January 2020

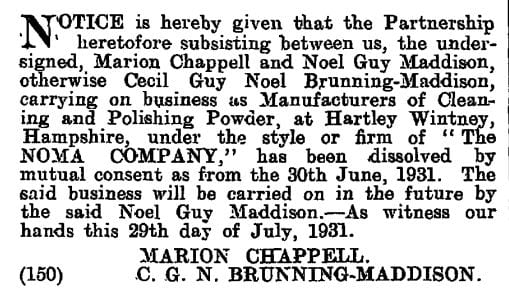

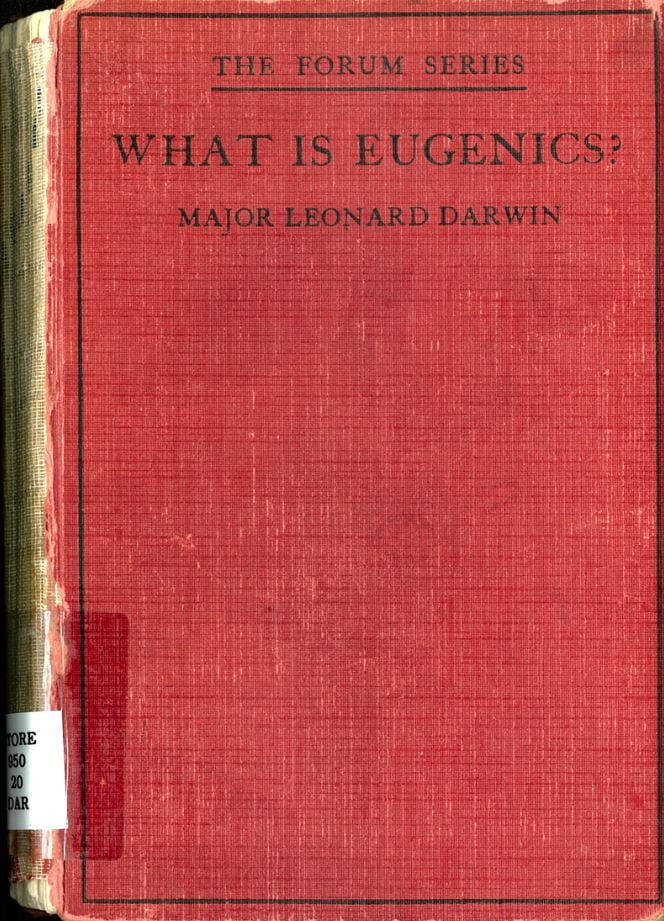

Being interested in Charles Darwin and his family, and also interested in his son Leonard, a few years ago I borrowed a copy of one of Leonard Darwin’s books from the UCL library store, What is Eugenics? (1928). The cover is rather tatty, well worn – the spine long gone. Inside the front cover of this small, slim volume (88 pages), is a book plate, pictured here –

Being interested in Charles Darwin and his family, and also interested in his son Leonard, a few years ago I borrowed a copy of one of Leonard Darwin’s books from the UCL library store, What is Eugenics? (1928). The cover is rather tatty, well worn – the spine long gone. Inside the front cover of this small, slim volume (88 pages), is a book plate, pictured here –

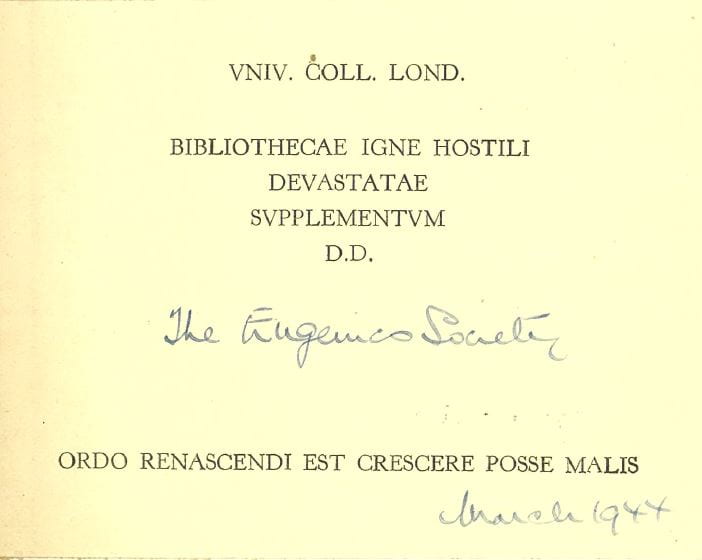

The book was one of those intended to replace UCL copies destroyed by bombing early in the war, as we see from the book plate. Then comes a quotation from Rutilius Namatianus, a 5th century Gallo-Roman poet, “Ordo renascendi est crescere posse malis” – roughly translated as “the essence of renewal is the ability to grow from your calamities.”

The book was donated by the Eugenics Society, in March 1944. Eugenics was a term coined by Sir Francis Galton, who was a cousin of Charles Darwin.

Turning to the short introduction, I saw a pencilled note, in Leonard Darwin’s hand. It refers to the chapter entitled, “THE DETERIORATION OF OUR BREED” – “If I had to write this again I should in Chapt XIII paint a more lurid picture.”

Leonard Darwin was the only one of Darwin’s sons not to have some sort of a science background. He joined the army, was for a short time an MP, and strongly supported the eugenics movement in Britain and internationally. At that time, eugenics was far from being a fringe belief, nor was it confined to people with right wing politics. Many of the views expressed in this book would have been widely held by educated people, particularly from the better off classes no doubt.

Throughout the book there are minor corrections that presumably were intended for a possible future edition. He also has in the last page, a calculation of the number of copies sold, 2,130 in the first two years of publication, 1,800 in 1933, then numbers dropping, but down to 181 sales in 1938. Interestingly,I wonder if the spurt in sales in 1933 was related to the election of Adolf Hitler, and the Nazi laws to allow for eugenic sterilization in May 1933.

The Chapters are as follows – the scans do not exactly correspond to the page numbers so the start of the next chapter may be with the previous scan. To see the pdf, having clicked on the link, then click on the grey pdf icon.

I. DOMESTIC ANIMALS wie 1-5 Cover, Contents & Introduction, & Ch 1

Attention to breed—Unconscious and conscious selection — Breeds of dogs, cattle, etc. — The farmer’s knowledge.

II. MAN’S ANCESTORS wie 4-15 Ch 2 & Ch 3

Improvements in mankind—Evolution and development, parallel processes — Struggle for existence —Natural selection.

III. OUR SURROUNDINGS

Acquired differences—Mutilations—Effects of education—Social contact—Large families and poverty.

IV. HEREDITARY QUALITIES wie 16-25 Ch 4, Ch 5, & start of Ch 6

Differences in mind and body at birth—Twins—Qualities of descendants—Regression to the mean.

V. EUGENIC METHODS

Stockyard methods—Overcrowding—Murder—Compulsory marriage—Birth rate, not death rate—Risks inevitable.

VI. THE MEN WE WANT wie 26-35 end of Ch 6, Ch 7, & start of Ch 8

Elimination of defectives—Supermen—Inferior castes — Men judged by performance— Equality never obtainable.

VII. INFERIOR STOCKS

Elimination of unfit—Compulsion or persuasion—Rare diseases—Insanity—Epilepsy—Consumption—Doctors’ advice.

VIII. BIRTH CONTROL wie 36-43 end of Ch 8, & Ch9

Checks on population—Family limitation—Continence—Contraception—Effects on health and morals —Dual campaign.

IX. STERILIZATION

Nature of operation—Not as punishment—Not compulsory — Promiscuous intercourse — Rapidity of results—Californian experiences.

X. FEEBLE-MINDEDNESS wie 44-55 Ch 10 & 11

Numbers— Causes — Heredity— Segregation— Guardianship—Sterilization—Marriage—Mental Deficiency Acts.

XI. THE HABITUAL CRIMINAL

Causes—Removal of children—Feeble-minded criminals — Reformatories — Training — Imprisonment —Segregation—Sterilization.

XII. WHO HO PAYS THE BILL ? wie 56-61 Ch 12

The Unfit—Taxation—Private charity—The inferior —Social contagion—Output of goods—The employ-able—The unemployed.

XIII. THE DETERIORATION OF OUR BREED wie 62-67 Ch 13

Differential birth rate — Multiplication of poorer classes—Effects produced—Conditions new—Decay of ancient civilisations.

XIV. EUGENICS IN THE FUTURE wie 68-73 Ch 14

Elimination of the inferior—Public assistance—Right to parenthood—Warnings as to size of family.

XV. BIGGER FAMILIES IN GOOD STOCKS wie 74-79 Ch 15

Small families—Character and wages—Morals and patriotism—Luxury—Ambition—Children’s welfare—Highly educated women.

XVI. FINANCIAL AIDS TO PARENTHOOD wie 78-83 Ch 16

Larger families, their causes and how to promote them—Family allowances—Income tax—Salaries—Scholarships.

XVII. SELECTION IN MARRIAGE wie 84-88 Ch 17

Benefits and disadvantages—Opportunities for meeting—Marriage with good stock—Cousin marriages—Medical certificates.

Interestingly, neither Leonard Darwin, nor Francis Galton, had offspring. Leonard Darwin died in 1943, and I suppose left his books to the Eugenics Society. Leonard Darwin had a long correspondence with the evolutionary biologist, R.A. Fisher that has been digitised – you can see that here – https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/3860

The book is now with UCL Special Collections.

You can read about Deaf people and eugenics, in Deaf People in Hitler’s Europe, edited by Donna F. Ryan and John S. Schuchman, Gallaudet University Press, 2002.

I have mentioned eugenics before in the blog – see the item ‘Breeders of the Deaf’.

This blog was edited on 9th of March and a few lines were removed that expressed a heavily qualified opinion.

Close

Close