William Cheselden (1688-1753) has been called “one of the most brilliant operators whose achievements are on record” (DNB 1921-2, p. 192). He was born in Burrough-on-the-Hill (but in the parish of Somerby), Leicestershire, and trained under William Cowper (1666-1709), an anatomist who was involved in an early plagiarism scandal.

William Cheselden (1688-1753) has been called “one of the most brilliant operators whose achievements are on record” (DNB 1921-2, p. 192). He was born in Burrough-on-the-Hill (but in the parish of Somerby), Leicestershire, and trained under William Cowper (1666-1709), an anatomist who was involved in an early plagiarism scandal.

Cheselden became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1712, and in 1713 published a student book, The Anatomy of the Human Body. He married Deborah Knight on the 24th of July, 1713, at St Olave, Bermondsey. She appears to have been the daughter of Thomas Knight, and niece of Robert Knight, the chief cashier of the South Sea Company, who escaped prosecution in connection with the accompanying ‘bubble’ in 1720. (Sir Robert Walpole’s rise to power was linked to Knight, the South Sea Company and its demise.) It seems that Cheselden invested £1,000 in the company in 1714, the same amount as Sir Isaac Newton. Perhaps he was ‘encouraged’ by his wife or her family.

Henrietta Howard (1689-1767), Countess of Suffolk, was born Henrietta Hobart at Blickling Hall, Norfolk. She had a very interesting life, but a very difficult one. She married Charles Howard, later 9th Earl of Suffolk. He was a gambler, and was violent towards her. Whether her hearing loss was caused by being abused by her husband, or from some other reason we cannot say. Her hearing loss was however central to her life, already seeming apparent in 1721. In 1727 she told Swift she had ‘a bad head and deaf ears’ (Borman, p.97). Alexander Pope wrote this of her –

I know the thing that’s most uncommon;

(Envy be silent and attend!)

I know a Reasonable Woman,

Handsome and witty, yet a Friend.

Not warp’d by Passion, aw’d by Rumour,

Not grave thro’ Pride, or gay thro’ Folly,

An equal Mixture of good Humour,

And sensible soft Melancholy.

‘Has she no Faults then (Envy says) Sir?’

Yes she has one, I must aver:

When all the World conspires to praise her,

The Woman’s deaf, and does not hear.

She was known for her discretion it seems – probably as she could not follow much of the gossip of court (ibid. p.98). Henrietta became a friend of Queen Caroline before the accession of George II, and later became one of the king’s mistresses. Cheselden became Surgeon to the Queen in 1727 (Cope, p.32). At that time doctors still had a very imperfect understanding of the hearing system, and new discoveries were being made. Cope says that Queen Caroline herself was “rather deaf” (Cope, p.32), and that as a consequence a ‘test’ operation was planned as an experiment on a prisoner, to find a cure or rather a treatment for deafness. This hearing loss or deafness is something unsubstantiated by any other source I have been able to find. Either Cope misunderstood, and substituted the Queen for the Countess, or he had some other information.

Charles Ree, Rey or Ray of St. Martin’s in the Fields was a barber. In 1730 he was “indicted for feloniously stealing 5 Silver Watches, value 30 l. in the Dwelling-House of Paul Beauvau, the 29th of October” (Old Bailey Records). he was sentenced to death, which was commuted to transportation.

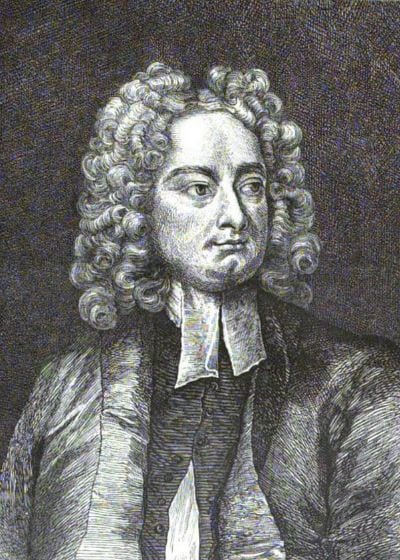

According to Horace Walpole,

“(112) Lady Suffolk was early affected with deafness. Cheselden, the surgeon, then in favour at court, persuaded her that he had hopes of being able to cure deafness by some operation on the drum of the ear, and offered to try the experiment on a condemned convict then in Newgate, who was deaf. If the man could be pardoned, he would try it; and, if he succeeded, would practise the same cure on her ladyship. She obtained the man’s pardon, who was cousin to Cheselden, who had feigned that pretended discovery to save his relation-and no more was heard of the experiment. The man saved his ear too – but Cheselden was disgraced at court.”

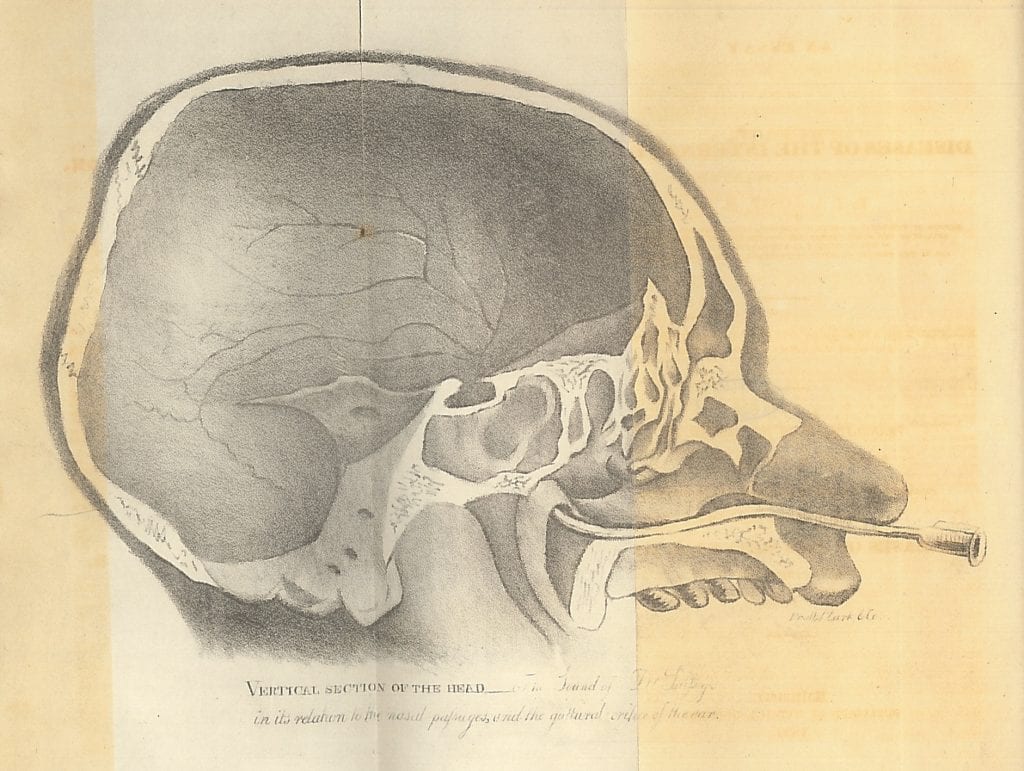

Here we have the report from the Monthly Intelligencer for January, 1731. It seems that Ray was to be reprieved from his sentence in return for being the guinea pig in an experiment to understand the role of the tympanum, in order to try to treat deafness.

The same volume of the Monthly Intelligencer continued the story, with an attack by ‘Quibus’ in an imagined lecture, which was written by Thomas Martyn, botanist.

And then continued on page 19 where a defence of the operation at the Royal Society is quoted.

The older Oxford DNB 1922 article says,

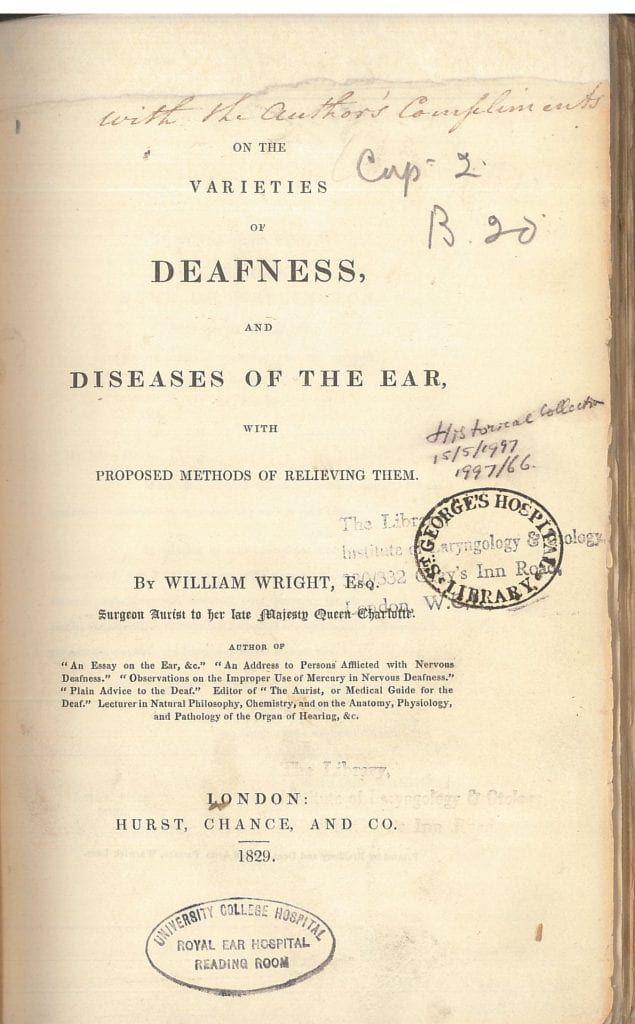

In December 1727 Cheselden was appointed surgeon to Queen Caroline. Later on he would appear to have been out of favour at court, and was not called in during the Queen’s last illness. An improbable story is told that Cheselden gave offence in high quarters by neglecting to perform a certain experimental operation on a condemned criminal. The proposed experiment consisted in perforating the membrana tympani, or drum of the ear, so as to show whether this part is the seat of hearing, and whether the operation could safely be done to relieve deafness. Cheselden in his Anatomy tells the story as follows : ‘Some years since a malefactor was pardoned on condition that he suffered this experiment, but he falling ill of a fever the operation was deferred, during which time there was so great a public clamour raised against it that it was afterwards thought fit to be forbid.’ Proposing the operation, rather than neglecting to do it, was more probably the offence.

The quote seems to be from the 1740 edition of the work.

In Sir Zachery Cope’s 1953 biography of Cheselden, he says that Walpole is incorrect, and that such an incident would be unlikely to lead to a loss of favour at court. “From the point of view of the health of the Queen her change of surgeon may well have been unfortunate for, as is well known, she died from the results of a strangulated umbilical hernia and Cheselden had already published an account of his successful treatment of such a hernia”. After her death Cheselden continued to be referred to as ‘surgeon to her late Majesty’ (p.35).

Gossip though he was, Horace Walpole knew the Countess well, so surley his information would have come from her? Borman says that Henrietta would listen to Walpole’s questions with a tortoiseshell ear trumpet, and almost whisper her replies (p.252). It seems unlikely that there was a familial relationship between Cheselden and Ray, but the rumour must have persisted. It is possible, but we would need to trace records for Ray before he was prosecuted. Is it possible that as Ray was a barber there was a connection with the barber-surgeons?

Cheselden was buried at the Royal Hospital in Chelsea. The Countess of Suffolk was buried in Berkeley Castle, with her second husband.

As for Charles Ray, the Ipswich Journal for Saturday the 6th of March, 1731, says “Charles Ray, who received Sentence of Death, but upon his submiting to have an Experiment try’d upon his Ear, by an eminent Surgeon, for the better finding out the Cause and Cure of Deafness, was afterwards order’d for Transportation; is continued in Jail, his Transportation being stopt.” The Caledonian Mercury for Tuesday the 30th of March, 1731, says “The Experiment that was to have been made on the Ear of Charles Ray, is now laid aside, and he is to have a free Pardon. ‘Tis to be feared, that as there has been so great a Clamour against this Experiment, neither this nor any other useful Experiment will ever be made this way.”

I wonder what became of him?

Here I have tried to sketch out the relationships between the people mentioned.

Borman, Tracy, Henrietta Howard, King’s Mistress, Queen’s Servant. Jonathan Cape, 2007

Charles Ray, John Winslow, Theft – theft from a specified place, Theft – receiving, 4th December 1730 Old Bailey Records

Cheselden, William. Anatomy of the Human Body. London: William Bowyer, 1712

Cope, Sir Zachery, William Cheselden, 1688-1752, E & S Livingstone, Edinburgh & London, 1953

Dictionary of National Biography, Volumes 1-22 London, England: Oxford University Press; Volume: Vol 04; Page: 192 1921-2 edition

Horace Walpole’s Letters p.141 & 148

John Kirkup, ‘Cheselden, William (1688–1752)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5226, accessed 22 Sept 2017]

https://epdf.pub/a-political-biography-of-alexander-pope-eighteenth-century-political-biographies.html

https://words.fromoldbooks.org/Chalmers-Biography/c/cheselden-william.html

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-75056?rskey=roxYmw&result=3

The sculptor was Cecil Walter Thomas (1885-1976), born in West London, and a student at the Slade (UCL). Thomas became known for his medallions and coins, that included work for the Royal Mint, as well as bronzes. He served in the army in the First World War, and was wounded, then later served in the Second World War.

The sculptor was Cecil Walter Thomas (1885-1976), born in West London, and a student at the Slade (UCL). Thomas became known for his medallions and coins, that included work for the Royal Mint, as well as bronzes. He served in the army in the First World War, and was wounded, then later served in the Second World War. Close

Close