“The pony was buried by the gardener” – Charles Baker and his ‘Graduated Lessons’ book, 1841

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 22 January 2016

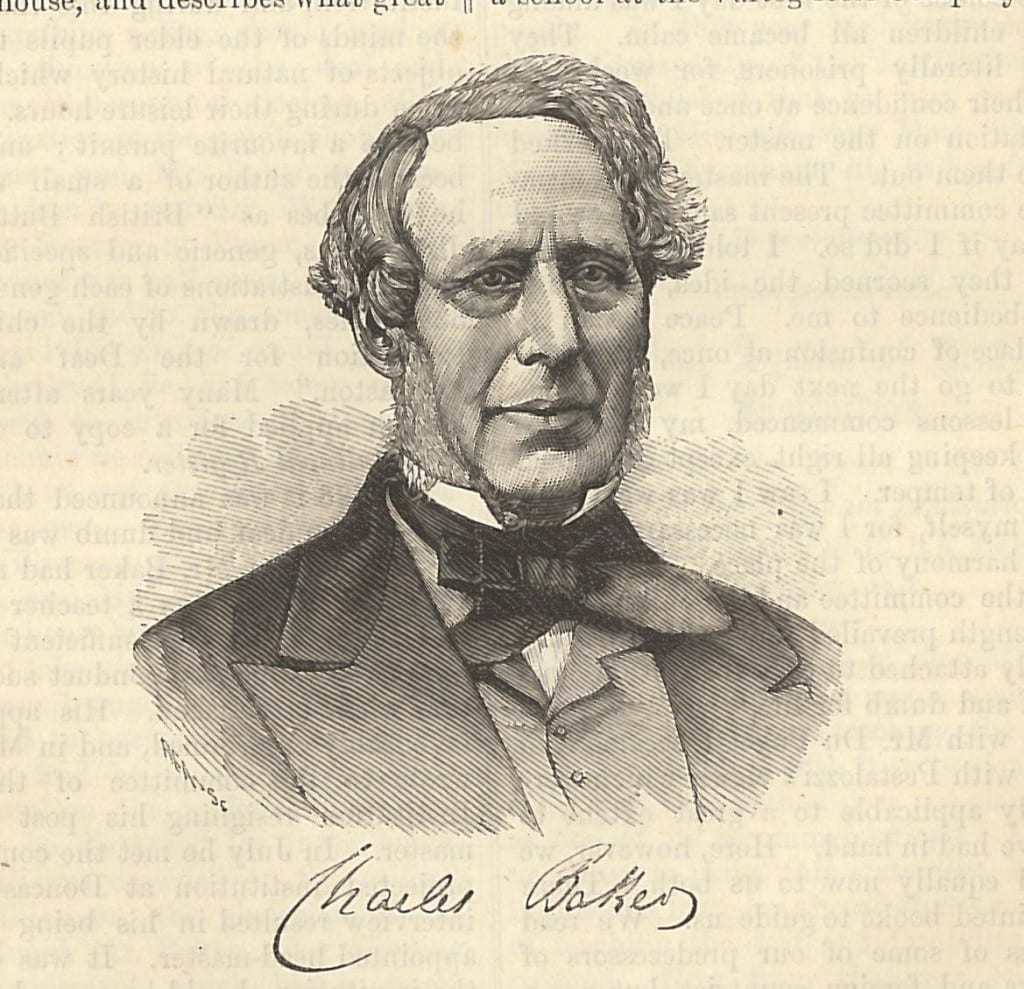

Charles Baker, (1803-74) was a teacher of the deaf, headmaster of the Yorkshire Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Doncaster. The biographical sketch in A Magazine intended chiefly for the Deaf and Dumb, ran into three sections, which shows how highly he was regarded at the time (pp.8-11, 24-8, 38-9). The article tells us that Charles, born in Birmingham on the 31st of July, 1803, was the second of thirteen children.

He was but a youth when his attention was first attracted to the deaf and dumb. His father, while walking with him one day, directed his attention to a gentleman, and informed him that he had just come to Birmingham to establish a school for the deaf and dumb. This excited his curiosity, and his father promised to take him to an examination of the deaf and dumb children. He went to the examination, and was much pleased with the intelligence and acquirement’s of the children. They were under the care of Mr. Braidwood, a grandson of the Braidwood who was the first teacher of that name in Great Britain. (ibid, p.8)

He taught at the Deritend and Bordesley (now suburbs of Birmingham) Sunday School when only fourteen. In this way he became known to “most of the leading men of the neighbourhood” (p.8). In 1818 he took charge of the School when Braidwood had to go away, but Baker said,

He taught at the Deritend and Bordesley (now suburbs of Birmingham) Sunday School when only fourteen. In this way he became known to “most of the leading men of the neighbourhood” (p.8). In 1818 he took charge of the School when Braidwood had to go away, but Baker said,

not a book used in their instruction was to be found. All had been carefully locked up, as though the craft would have been in danger if a boy of fifteen had been allowed to penetrate into its mysteries. However, there were copy-books, drawing-books, pictures, and writing and drawing materials. Some hours were spent each day in improving work, and the rest in play, and long walks about the beautiful neighbourhood.

Some of the “gentlemen connected with the Institution wished to engage him permanently as an assistant, but Mr. Braidwood’s consent could not be obtained” (ibid). Aged seventeen Baker went to teach at Wednesbury, in the school established by the Quaker businessman Mr. Samuel Lloyd (of the banking family) remaining there for two years (ibid p.9). At that time he made the acquaintance of the Rev. William Jackson who had married the widow of a Captain White Benson of York. It was there that he met Edward White Beson, who became Charles’s friend and married his sister, Harriet Baker. Their son Edward became Archbishop of Canterbury. When Charles was twenty, he moved to Wales, running a school at the Vartag Iron Company’s Works in Pontypool, stay there until 1826 (ibid p.9).

Some of the “gentlemen connected with the Institution wished to engage him permanently as an assistant, but Mr. Braidwood’s consent could not be obtained” (ibid). Aged seventeen Baker went to teach at Wednesbury, in the school established by the Quaker businessman Mr. Samuel Lloyd (of the banking family) remaining there for two years (ibid p.9). At that time he made the acquaintance of the Rev. William Jackson who had married the widow of a Captain White Benson of York. It was there that he met Edward White Beson, who became Charles’s friend and married his sister, Harriet Baker. Their son Edward became Archbishop of Canterbury. When Charles was twenty, he moved to Wales, running a school at the Vartag Iron Company’s Works in Pontypool, stay there until 1826 (ibid p.9).

Back in Birmingham he was asked back to the Birmingham School. After Braidwood died, Louis du Puget, a pupil of the Italian teacher Pestalozzi became the headmaster. Unfortunately he struggled to control the pupils.

Mr. Du Puget was an intelligent man and a good teacher, but not specially qualified for the teaching of the deaf and dumb. I was called upon, and most urgently requested by Dr. De Leys and Dr. Alexander Blair, to go again and assist in the management of the institution; they represented the place as being in a state of utter disorganization and confusion, the lads running away at the rate of three or four a day, and the girls in rebellion, the matron disaffected like the children towards the master, and the assistant master, who had resided there for several years, had gone away. At first I positively and firmly declined any such engagement, but the picture they drew of the position of affairs, threatening the very existence of the institution, induced me at last to promise to pay a visit to the institution the next day.

In the course of the first day I was among them, the children all became calm. They had literally been prisoners for weeks. I obtained their confidence at once and without any imputation on the master. […] I saw I was weaving a net round myself, for I was necessary to the continued harmony of the place. The solicitations of the committee and the children and others at length prevailed so far that I became permanently attached to that institution, and to the deaf and dumb for life.

While with Mr. Du Puget I became well acquainted with Pestalozzi’s views, which were undoubtedly applicable to a great extent to the work in hand. Here, however, we had a field equally new to both of us. There were no printed books to guide us. We read the theories of some of our predecessors of ancient days and foreign countries, but not a scrap of practical information as to modes of procedure had been left behind by those who had previously occupied our position. Night after night we worked almost in the dark at courses of instruction in language, and day after day we taught during school-hours and discussed at other times different modes of conveying the knowledge of the English language to our pupils. I had now made up my mind that it was no ignoble office to walk in the steps of Dalgarno, Wallis, Braidwood, De l’Epee, Sicard, and others who had devoted their thoughts and their lives to raising the condition of those who, deprived of hearing, have never attained, or if once attained have lost, the power of speech. (ibid, p.9-10)

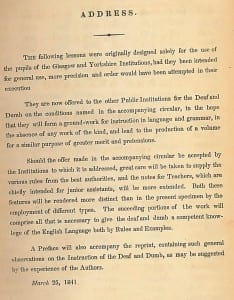

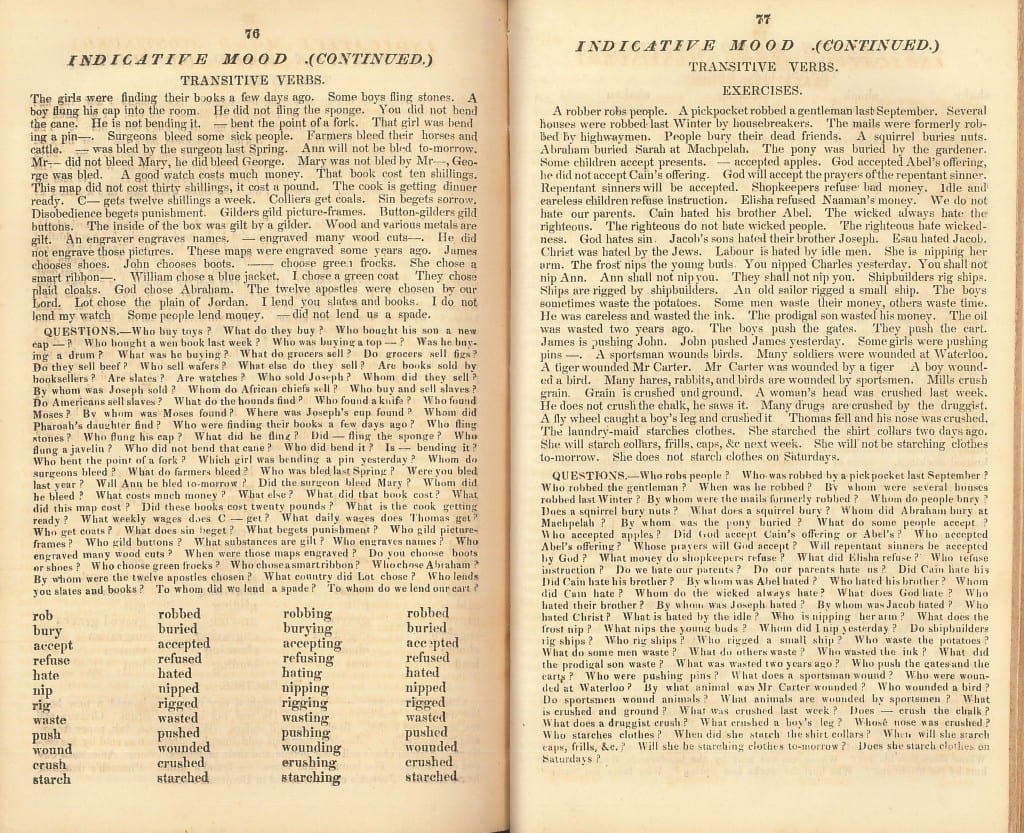

Our copy of the book he co-wrote with Duncan Anderson of the Glasgow Institution, published in 1841, was acquired by Charles Rhind in 1842, when he was teaching in Belfast. Rhind seems then to have made a practice of obtaining books on various educational methods. Above in the introduction we see that this book came with the offer of notes for teachers. The examples of sentences in the following picture are intriguing. Click the images for a larger size.

- “Ann will not be bled tomorrow.”

- “The pony was buried by the gardener.”

- “A tiger wounded Mr. Carter.”

- “A woman’s head was crushed last week.”

Baker resigned from his Birmingham post in 1829, moving to Doncaster to open the new school there. When the school was established, he turned his mind to producing educational material, and in 1831 published his first educational book, with many more to follow. He was a pioneer in producing this type. A list of his works can be seen here.

Baker resigned from his Birmingham post in 1829, moving to Doncaster to open the new school there. When the school was established, he turned his mind to producing educational material, and in 1831 published his first educational book, with many more to follow. He was a pioneer in producing this type. A list of his works can be seen here.

The private library of Charles Baker, is now in the archives of the Edward Miner Gallaudet Memorial Library, Gallaudet University, Washington, D.C.

Baker, Charles and Anderson, Duncan, A series of graduated lessons in language and grammar, for the instruction of the deaf and dumb. Doncaster, 1841.

Biography. Magazine intended chiefly for the Deaf and Dumb, 1876, 4, 8-11, 24-28, 38-39.

BOYCE, A.J. The Baker Collection. Deaf History Journal, 2000, 4 (2), 22-34.

Picture lessons for boys and girls translated from the French of Valade-Gabel by Charles Baker. No date. Historical Collection.

C. W. Sutton, ‘Baker, Charles (1803–1874)’, rev. M. C. Curthoys, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1109, accessed 22 Jan 2016]

We have more of Baker’s books.

One Response to ““The pony was buried by the gardener” – Charles Baker and his ‘Graduated Lessons’ book, 1841”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] Teacher of the Deaf. Born on the 29th of June, 1838, at Marsden, he began his teaching life with Charles Baker at Doncaster, and was, according to The British Deaf-Mute ‘“articled” after a […]