Emergent Brazilians comment the impeachment of the president

By Juliano Andrade Spyer, on 2 September 2016

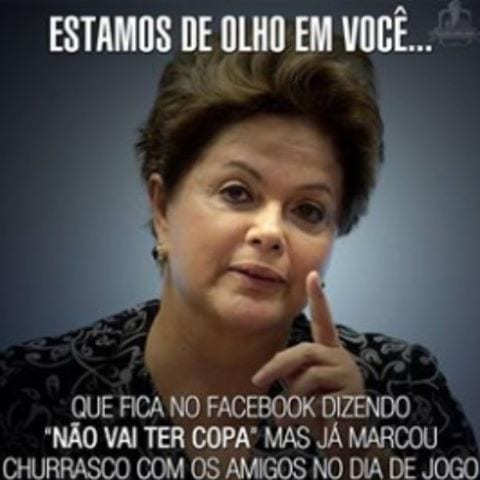

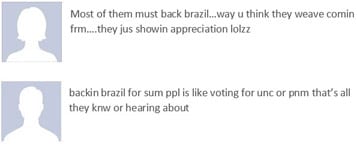

This is one of the memes circulating among low income Brazilians in reference to the impeachment of President Dilma. The top comment says: “Gosh, is this true?” Below the image it reads: “‘I do not recognise the new Brazilian government’, says Obama, threatening to close the American embassy…

One of the latest hot topics of research in Brazilian social sciences is the extreme polarisation of opinions in the country. Social media was at the centre of the street protests of June 2013. The impression then that the internet was unityfing Brazilians against corrupt politicians. However, only a few months later online communication apparently helped to intensify tensions between groups in society. In my (educated middle class) circle, for example, almost everyone (if not everyone) has experienced “unfriending” or being “unfriended” on Facebook because of different political views. (If you are not following the news about the political crisis in Brazil, read about it here.)

But I wonder how lower income Brazilians were perceiving the same events and how they viewed the Senate’s decision to impeach the president. Thanks to WhatsApp, it was easy to contact them and quickly get some answers, which I translated and added below. Similarly to the educated middle class, these emergent Brazilians are also following closely this debate, partially because of the television coverage, but also independently via social media through the exchange of memes – see images at the top and at the end of the post. They are also divided in regards to supporting or not the Senate’s final decision, but three out of the four informants considered the impeachment unfair. More interestingly, though, is to note how the intensity of debates has enriched their understanding of government politics.

Opinion 1: “Fair? The condemnation did not have plausible arguments and just to have peace of conscience they did not take away her political rights”, which should be the legal outcome of an impeached president.

Opinion 2: “My son cannot take a test in his (public) school because they don’t have paper and the privately hired staff are 3 months without receiving salaries. I am against the government because of the matter of education. In the last few years my son has had only one or two classes per week. Both the governor and the mayor are from the Worker’s Party [same as the president], and they have been in charge for the past 12 years. I think the impeachment was unfair for the particular reason presented, but fair for the overall situation. I have many friends that are unemployed.”

Opinion 3: “In my opinion it was not fair because it was the people who elected her. To be honest, I wanted her to leave, but I would like to choose who would replace her. To some Brazilians like me, it is as if we have no voice and the only thing we can do is to wait for the country to fall to pieces, and we are the country. I feel sad because instead of advancing we are going backwards. Public education is weak, health services are worst and I do not need to comment about violence.”

Opinion 4: “I feel things will get worst. I am worried. The new government did not receive the votes from the people and they will govern wrongly. ‘We will have to pay the price in the future.’”

Below, some of the memes they are circulating.

It says: “In the Senate, Bahia is the only state that voted unanimously against the impeachment…”

It says: “In his speech, Temer [the new president] says he will not tolerate to be called a coup leader”.

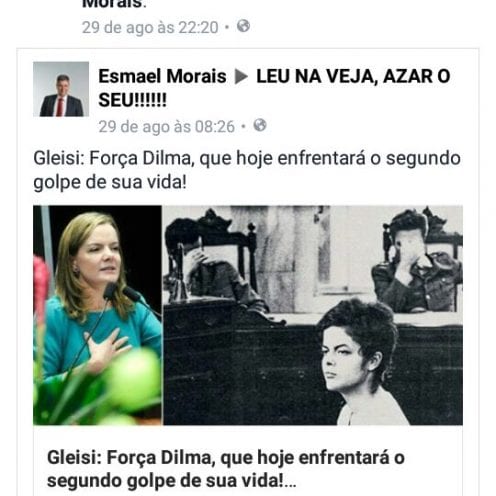

It says: “Gleisi: Be strong, Dilma. She is facing the second coup of her life today.”

It says from top left: “Home of the mayor, home of the city councilmen, home of the secretary. HOME OF THE VOTERS.”

Close

Close