Inhabiting Resistance: Stories from Thamrin – Portraits of Circumstances and Their Human Beings

By Dana Sousa-Limbu, on 28 July 2025

By Benedictus Bagustantyo

“Even if ‘I shed my blood’ (tumpah darah), even until my death, I will remain here!

This is ‘my birthplace’ (tanah tumpah darahku)[1],

passed down through generations – my rightful property.

As long as I live, there is no way I will ‘leave’ this house,

not even a single step.” (Elis, 2019a)

Elis’ declaration above is a poetic lament – part cry, part promise, entirely powerful – that has resonated in my mind since I heard her story (singular), which went viral across mainstream and social media in 2019. Elis suddenly drew media attention because her 40-square-metre humble house is tucked away within a 45-story upper-middle-class apartment complex in the Thamrin area, Central Jakarta (see Figure 1). It is located in one of Indonesia’s most expensive areas, just less than one kilometre from the Bundaran HI, with its “Welcome Monument”. Moreover, her house is one of the last remains of Kampung[2] Kebon Melati, a neighbourhood slowly disappearing due to urban development. Even though the apartment developer has offered compensation at a “reasonable” price, Elis refuses to relocate from the land and house that her ancestors inherited. In other words, she has chosen to assert the main essence of what Harman (1984) calls the “right to stay put”. However, while asserting such a right, Elis attracted numerous adverse remarks on the media coverage, with many deeming her irrational, doubting her resilience, and advising her to sell her inheritance and leave immediately.

Therefore, this essay seeks to retell her housing stories (plural) – in contrast to the singular narrative the media have covered, to uncover what circumstances shaped Elis’s form of inhabited resistance. It will focus on Elis’ tenacity intertwined with the history fragments of her house and her kampung as a form of unlearning and “storytelling otherwise” (see Lorimer, 2003, p. 283; see Ortiz, 2023). Her narratives act as a starting thread that unravels further stories reflecting on urban development trajectories in Jakarta, especially in seeking and formulating housing policies toward housing justice (see Cociña & Frediani, 2024). Situating her specific housing stories within broader circumstances will show how personal and political dynamics intersect to produce distinct housing decisions, processes, and consequences (see Lees & Robinson, 2021, p. 594). Nevertheless, this essay is a gesture toward justice for Elis – recognising her, understanding her, and not letting her stories fade.

Thus, the stories will unfold in three distinct acts to pursue the mentioned aims, each corresponding to a critical juncture in Indonesia’s historical timeline while also implying its semantic meaning: the “Old Order”, the “New Order”, and the “Reformation”. Ultimately, this essay will reflect on how the stories extend beyond Elis and her family, home, or neighbourhood (kampung and the apartment). It calls attention to broader questions of belonging, memory, housing and urban justice that implicate us all.

Figure 1. Elis’ house within an apartment complex in Thamrin, Jakarta.

Source: (Lova, 2019 in Kompas.com)

The “Old Order”

“You could say this house holds memories – ones we cannot forget. It also carries the legacy of my wife’s parents, who were freedom fighters.” (Chairul B., 2019).

Elis was born in 1955 – in the mid-period of the Old Order era (1945-1966), a period born from the struggle for Indonesia’s long-awaited independence. Chairul, her husband – whose quote opens this section – was born in 1947. They entered a world shaped by the nation’s attempt to translate freedom into governance and ideals into action. Perhaps Elis’ soul of resistance was no coincidence; it was a legacy inherited from her parents, who once fought for the republic. During that time, in the spirit of hope, waves of people from various regions across Indonesia left their hometowns, searching for opportunities and a better future in Jakarta. Due to this migration, the capital city experienced explosive population growth – from around 800 thousand in 1949[3] to around 3.5 million in 1965 (Cybriwsky & Ford, 2001). Unlike the migrants, Elis (2019c) asserts her identity as a native Jakartan (also known as Betawi), “I am from the eighth generation [living in this place] – truly rooted here, not someone who came from elsewhere.”

Like Elis, her home had long taken root and grown in the Tanah Abang district, precisely in Kampung “Kebon Melati” (Jasmine[4] Garden). Her kampung name indicates the origins of its settlement, part of a broader pattern in Jakarta where place names echo the natural produce that once flourished there. Zaenuddin (2012) notes that the official naming of the neighbourhood as “Kebon Melati” did not occur until the 1960s. However, the “blooming” from jasmine fields to a settlement had begun long before –around 1897-1935 – as a southern extension of the earlier Kampung “Kebon Kacang” (Peanut Plantation). Accordingly, Kebon Kacang Street was the primary pathway to Kebon Melati until the second millennium. Its strategic location – close to the historic Tanah Abang market and the city center (Weltevreden), sparked this housing process. These claims are supported by the historical maps of Batavia[5] below, depicting the spatial transformation.

Figure 2. Maps of Batavia during the pre-independence period.

Source: (Based on KITLV, 2025).

However, the historical maps and legends above also imply that kampungs were viewed as “indigenous neighbourhoods” segregated from Batavia based on race. It was an exclusionary and oppressive practice commonly seen during the colonial era (Putri, 2019). Furthermore, it substantiates Irawaty’s (2018) note that kampungs were often associated with disorder, disease, and ignorance due to their physical aspects in contrast to European and Chinese areas. Jellinek (1991, p. 2) describes the typical native Jakartans’ houses around Kampung Kebon Kacang in the 1940s as often built with woven bamboo walls and thatched coconut palm roofs and rested on land – which typically held legal title. Kampung Kebon Melati, too, reflects a similar pattern; Elis (2019c) recalled, “Back then, all [the floors inside the house and the road outside] were made of nothing but bare earth.” – a stark contrast to the beauty and fragrance of the jasmine flower that once filled the area.

Nevertheless, the true beauty of the kampung does not lie in its physical form but in the spirit and soul that breathes life into it. Just like Elis, who showed a form of resistance, Putri (2019) argues that historically, kampung embodied a collective form of defiance against colonialism. This assertion is because the settlement process was a community response to the exclusion and oppression experienced by the people during the Dutch colonial era. They formed and maintained traditional and informal socio-economic networks as opposed to colonial modernity. Moreover, Jellinek (1991, pp. 1–17) draws attention to the unique beauty of Jakarta’s kampung, especially during the Old Order period. She describes it as a lived social space bound by interpersonal connection where support and sociability were part of the everyday rhythm – driven by kinship and rooted in collective care rather than financial gain. Altogether, the mentioned elements rendered the kampung as both a source of insurgency and solidarity – anchoring the hopes of its inhabitants.

Ironically, President Sukarno – the founding father who was known to be anti-colonial – “threatened” the kampungs by embracing a vision of progress rooted in colonial modernity (Putri, 2019). With an architectural background, he spearheaded the modernisation of Jakarta, envisioning it as a great city with skyscrapers, monuments, and grand boulevards (Cybriwsky & Ford, 2001). This wave of development began in the 1950s when Elis was born and reached its peak during the preparation for the 1962 Asian Games. The key projects included the National Monument, the Senayan sports complex, and Kebayoran Baru (a new suburban residential district). Linking them together was Thamrin Boulevard, a broad avenue with the mentioned monumental roundabout – “Welcome Monument” (Ngantung, 1977; Sostroatmodjo, 1977). Moreover, Sukarno planned to replace kampungs with “modern” social housing (rusunawa). Although this plan to displace kampungs failed to proceed due to budgetary limitations and shifting political dynamics, numerous kampungs were uprooted for those earlier modernist projects (Irawaty, 2018). Fortunately, Elis’s home and her kampung remained standing despite being located precariously close to these development initiatives.

Figure 3. Maps of Jakarta illustrating the city’s transformation from 1960-1970.

Source: (Based on Merrillees, 2015).

The “New Order”

After an ambitious wave of modernisation, Indonesia’s economic and political stability declined, leading to Suharto’s rise to power in 1966. In this authoritarian New Order era, the nation’s course and economic priorities were set through Repelita – a series of Five-Year Development Plans. The new Governor of Jakarta (1966-1977), Ali Sadikin, had to deal with a population surge, rising housing demand, and kampungs’ inadequate physical conditions, but with fiscal constraints. He initiated the Kampung Improvement Program (KIP) in 1969, which became part of the Repelita I-III. The program emphasised upgrading infrastructure and improving living conditions in kampungs. It was conceived as a low-cost alternative to full-scale urban redevelopment and presented a more feasible solution than constructing new housing projects. Echoing the naming of Thamrin Boulevard, the KIP was also referred to as the Muhammad Husni Thamrin (MHT) Project in honour of a Betawi city legislator who had advocated for kampungs improvement during the colonial era (Irawaty, 2018; Silver, 2008). Remarkably, while not one of the official pilot projects, Kampung Kebon Melati became one of the first kampungs to experience the KIP during Repelita I (1969-1974).

Afterwards, Elis and her home in Kampung Kebon Melati become woven into the historical fabric of the KIP’s implementation – an unstated but lasting presence in the ongoing story (see Figure 4). A footpath was constructed on the east side of Elis’ house, transforming what was once bare earth into a concrete walkway around two metres wide. It extended southward, connecting her home to a nearby field and northward to the new vehicle road that had also undergone improvements. Although the road was only constructed along specific segments, it visibly improved accessibility to Kampung Kebon Melati. Furthermore, within 100 metres of her home, new communal water and sanitation facilities had been introduced. In addition, a new drainage system was constructed for flood prevention, and integrated waste disposal points were established. Lastly, parts of Kebon Melati that remained untouched by this initial phase were later addressed under KIP Repelita II (see Harari & Wong, 2024, p. 60).

Figure 4. The KIP implementation of Kampung Kebon Melati.

Source: (Based on Harari & Wong, 2024, p. 60)

Starting in Repelita II (1974-1979), coinciding with neoliberalism’s emergence in Indonesia, the KIP gained financial support from the World Bank after the initial government-funded KIP Repelita I was deemed a success (see World Bank, 1995). The program later scaled up nationwide and earned international acclaim – the Aga Khan Award in 1980. However, Jellinek (1991) found that the KIP was often implemented without prior consultation with the affected communities – overlooking their most urgent needs. It failed to address underlying structural problems regarding access to land and housing, which drove up land prices in the improved kampungs (Putri, 2019). Then, many landowners became increasingly interested in selling or raising rents, forcing tenants to relocate to other kampungs on the urban periphery. Parallelly, in the 1990s, the KIP ended and evolved into urban renewal projects, often involving evictions and social housing construction (Irawaty, 2018). Eventually, the total area of kampungs demolished for public or private development was larger than that of kampungs improved under KIP (Putri, 2019). Kampung Kebon Melati was one of those nearly “demolished” by the urban development.

The “Reformation”

Figure 5. The gentrification of Kebon Melati from 2002–2023.

Source: (Based on Google Earth, 2025)

In 2005 – more than 30 years after the KIP in Kampung Kebon Melati, Elis received an offer from a developer to sell her land for 2.5 billion Rupiah. The developer – a consortium of a private firm and a regional-owned enterprise – planned to construct high-rise apartments to meet the upper-middle class’s housing and investment demands. However, as the land title holder, she firmly rejected the proposal, “No matter how much I am offered, I refuse to sell.” She also refused when the offer was changed to an apartment unit. For Elis (2019d), her stance was not about financial matters but about upholding principles intertwined with immeasurable sentimental value, “…[the house is a] proof of my family’s blood and sweat for years…” Her resistance was at once profoundly personal and structurally resonant, as it mirrored the broader trends reshaping Jakarta’s urban landscape during this new era.

At that time, Jakarta experienced a real estate boom, and private developers actively pursued opportunities to build modern dwellings (e.g., apartments) in inner-city and peripheral areas (Kusno, 2012). This phenomenon was driven by policies enacted at the end of Suharto’s regime, which increasingly turned land and property into valuable commodities (Leaf, 1992). Fuelled by the post-1998 crisis recovery, it stimulated the speculation practice that influenced the direction and pace of urban growth, favouring the upper-middle class (see Kusno, 2013). As indicated earlier, these shifts triggered kampung and their low-income settlers’ displacement and gentrification (Silver, 2008). Due to its strategic location, Kampung Kebon Melati became a prime target for property developers to acquire and invest in. As Elis and one of the neighbourhood unit leaders recounted, depending on tenure security, many gave up their land – lured by offers, afraid of eviction, or frightened by intimidating figures whose origins remained unknown (Azhari, 2019b; Elis, 2019a). Nevertheless, Elis chose to stay put – neither intimidated nor tempted.

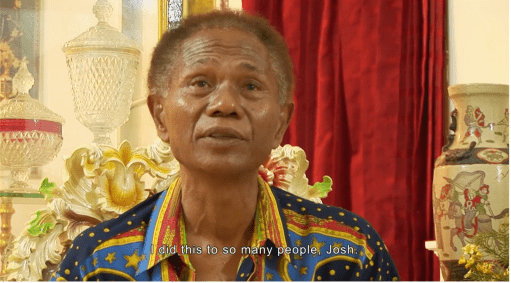

Moreover, Elis also persists in the conditions of what Lees and Robinson (2021) describe as the “slow violence of gentrification”, which started in 2009 when the apartment’s construction began. Elis (2019c) portrayed what her life was like during this phase, “…[D]uring the apartment construction, I could not even sleep; I was constantly drowsy. Night felt like day, and day like night… we were showered in dust every single day.”

Subsequently, roughly eight years after the apartment complex was built, the world around her has changed. Their two oldest children have grown up and settled in the urban periphery – but Elis remains with her husband and their youngest son at her parents’ inherited house. Yet, the house is now concealed by the retaining wall – visible only from above – and can only be accessed via a steep concrete ramp. Regarding this issue, she likened her experience to grey hairs hidden beneath dye – an honest presence yet made invisible. She lamented the lack of access, sunlight, and clean water – things that were once taken for granted.

“…I am walled in on all sides; how can I get out?… [Moreover,] all [the water] gets sucked by the apartments. I never get a share of clean water. [For daily needs,] I must buy refilled water in gallons… We carry the water gallons ourselves. That is why when it rains, and the ramp gets slippery, it is easy to fall. I have even hurt my back because of it.” (Elis cited in Azhari, 2019a).

Lastly, Elis (2019b) recalled how her surroundings used to be filled with houses – some inhabited by migrants drawn to the capital with hopes for a better future. However, now, she lives encircled by skyscrapers – separated from the remaining parts of Kampung Kebon Melati across the western edge. The shared facilities that had stood for years no longer existed. Even the field to the south, where children used it as a playground, has also been transformed into another apartment complex. For those who stayed, the narrow alleys have become the only shared and binding spaces (Oktarina, 2018). “Thamrin”, which once provided Kampung dwellers with their main access to the city’s wealth, seemed no longer open to them.

Figure 6. The access ramp to Elis’s house.

Source: (Lova, 2019 in Kompas.com)

In 2024, five years after her story went viral, it was reported that Elis still lived with Chairul and her youngest child in the same house. Under similar circumstances, they survived living “side-by-side” with the apartment. However, when she was about to be interviewed by the media, Elis refused, possibly concerned that media coverage could lead to further misunderstandings with various parties, including the apartment management, with whom they are now coexisting peacefully (see Murti, 2024; see also Aragon, 2019). She said, “…[M]au ngapain [lagi] nih?…” – “What [else] is there to do [or to say]?” Hereafter, her question became ours.

Afterwords

The just-mentioned question distances us as though urging us to reflect on what a just settlement for Elis and those like her could mean. From the revealed stories, it is highly possible that just settlement does not view housing as a commodity but instead challenges the hegemony of the top-down and market-driven approach. It involves people like Elis, who are (usually) excluded, as the subjects in every urban planning and development process. In this context, housing justice means recognising people, especially the low-income communities, their dwelling processes, and their relationship to land. This understanding aligns with Turner’s (1972) perspective, which views housing as a verb, emphasising the process and the relationship between dwellers and their homes. This transformative viewpoint also addresses the very question of what can be done for those clinging to the vestiges of previous regenerations, especially in (the remains of) Kampung Kebon Melati. They are the ones that are torn apart and must be reintegrated into the urban fabric through genuine participation and recognition, considering that Kampung is indeed an inseparable part of the city (see Kusno, 2020; see also Fraser, 1995, 2009). Mirroring Elis’ resistance, collective housing such as kampung susun is now emerging in Jakarta, emphasising housing as a verb and challenging the dominant trend of urban practices that are exclusionary towards housing justice (see ACHR, 2023; see Sari et al., 2022). However, this struggle is something that must continue to be fought for.

Therefore, Elis’ stories are a powerful reminder of the enduring significance of the right to stay put in the face of overwhelming development pressures and the slow violence of gentrification. Her resistance unravels kampungs as sources of insurgency, solidarity, and hope, which have always tried to be eliminated by distinct power dynamics shaping the urban trajectories. This occurrence highlights the need for the continued decolonisation of urban planning and development policies towards housing justice in Jakarta. Thus, even if individual, agency is crucial in questioning dominant logics that prioritise the exchange value of land and housing over their use or emotional value. Nevertheless, what seemed like stillness was, in fact, full of movements for the right to the city. Elis, her house, and Kampung Kebon Melati, which have persisted across eras, adapt without losing their spirit, ultimately become part of Jakarta’s journey and help contest the city’s future.

Acknowledgements

Although the author has never met Elis in person, she is sincerely appreciated for her stories, which have inspired and ensouled this essay. All information about Elis has been drawn from publicly accessible and credible sources, with care taken to ensure respectful and accurate representation.

References

ACHR. (2023). Kampung Akuarium (Case Studies of Collective Housing in Asian Cities Series). Asian Coalition for Housing Rights. http://achr.net/upload/downloads/file_230824171816.pdf

Anderson, B. R. O. (1999). Introduction. In P. A. Toer, Tales from Djakarta—Caricatures of Circumstances and their Human Beings (pp. 11–16). Cornell University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv1nhnxj.4

Aragon, H. H. (2019, September 23). Kisah Pemilik Rumah Tua, Bertahan Hidup di Halaman Thamrin Residence [’The Story of an Old House Owner Surviving in the Yard of Thamrin Residence’]. brilio.net. https://www.brilio.net/duh/kisah-pemilik-rumah-tua-bertahan-hidup-di-halaman-thamrin-residence-190923t.html

Azhari, J. R. (2019a, September 22). [Review of 7 Fakta Rumah Reyot di Tengah Apartemen Mewah [’7 Facts About a Ramshackle House Amid Luxury Apartments’], by S. Asril]. Kompas.com. https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2019/09/22/09164551/7-fakta-rumah-reyot-di-tengah-apartemen-mewah-kesulitan-pemilik-hingga

Azhari, J. R. (2019b, September 23). [Review of 5 Fakta Kampung Kebon Melati Terkepung Pencakar Langit di Thamrin [’5 Facts About Kampung Kebon Melati Surrounded by Skyscrapers in Thamrin’], by E. Patnistik]. Kompas.com. https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2019/09/23/09284281/5-fakta-kampung-kebon-melati-terkepung-pencakar-langit-di-thamrin

Chairul B. (2019, September 28). Seputar Rumah Kecil yang Berhimpitan Dengan Apartment Mewah di Tengah Ibukota [’About a Small House Tucked Between Luxury Apartments in the Heart of the Capital’] (The Newsroom NET. & N. Soekarno, Interviewers) [Interview]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzGbK2Pz67w

Cociña, C., & Frediani, A. A. (2024, April). Towards Housing Justice: Four propositions to transform policy and practice. IIED, London. https://www.iied.org/22321IIED

Cybriwsky, R., & Ford, L. R. (2001). City Profile: Jakarta. Cities, 18(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(01)00004-X

Elis. (2019a, September 20). Cerita Pemilik Rumah Bertahan Hidup di Halaman Thamrin Executive Residence [’The Story of a Homeowner Surviving in the Yard of Thamrin Executive Residence’] [Merdeka.com]. https://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/cerita-pemilik-rumah-bertahan-hidup-di-halaman-thamrin-executive-residence.html?

Elis. (2019b, September 20). Rumah Reyot “Nyempil” di Tengah Apartemen Mewah Jakpus, Ini Kisah Sang Pemilik [’A Dilapidated House ‘Wedged’ Among Luxury Apartments in Central Jakarta: The Owner’s Story’] (K. C. Media, Interviewer) [Kompas.com]. https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2019/09/20/16180581/rumah-reyot-nyempil-di-tengah-apartemen-mewah-jakpus-ini-kisah-sang

Elis. (2019c, September 21). Kisah Rumah Tua di Tengah Kompleks Apartemen Mewah [’The Story of an Old House in the Middle of a Luxury Apartment Complex’] (A. Santoso, Interviewer) [Detiknews]. https://news.detik.com/berita/d-4716088/kisah-rumah-tua-di-tengah-kompleks-apartemen-mewah?page=1

Elis. (2019d, September 22). House That Can’t be Moved (S. Atika, Interviewer) [The Jakarta Post]. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/09/22/house-that-cant-be-moved-owner-stands-ground-despite-being-boxed-dwarfed-by-skyscraper.html

Fraser, N. (1995). From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a Post Socialist Age. New Left Review, I(212). https://newleftreview-org.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/issues/i212/articles/nancy-fraser-from-redistribution-to-recognition-dilemmas-of-justice-in-a-post-socialist-age

Fraser, N. (2009). Reframing Justice in A Globalizing World. In Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in A Globalizing World.

Harari, M., & Wong, M. (2024). Slum Upgrading and Long-run Urban Development: Evidence from Indonesia. University of Pennsylvania. https://real-faculty.wharton.upenn.edu/harari/wp-content/uploads/~harari/HarariWong_SlumUpgrading_Sept2024.pdf

Hartman, C. (1984). The Right to Stay Put. In C. C. Geisler & F. J. Popper (Eds.), Land Reform, American Style (pp. 302–318). Rowman & Allanheld.

Irawaty, D. T. (2018). Jakarta’s Kampungs: Their History and Contested Future [UCLA]. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55w9b9gg

Jellinek, L. (1991). The Wheel of Fortune: The History of a Poor Community in Jakarta. University of Hawaii Press.

Kusno, A. (2012). Housing the Margin: Perumahan Rakyat and the Future Urban Form of Jakarta. Southeast Asia Program Publications at Cornell University, 94, 23–56.

Kusno, A. (2013). After the New Order: Space, Politics, and Jakarta. University of Hawai’i Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqhg1

Kusno, A. (2020). Middling urbanism: The megacity and the kampung. Urban Geography, 41(7), 954–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1688535

Leaf, M. L. (1992). Land regulation and housing development in Jakarta, Indonesia: From the “big village” to the “modern city” [Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley]. In ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (304054188). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/land-regulation-housing-development-jakarta/docview/304054188/se-2?accountid=14511

Lees, L., & Robinson, B. (2021). Beverley’s Story. City, 25(5–6), 590–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2021.1987702

Lorimer, H. (2003). The Geographical Field Course as Active Archive. Cultural Geographies, 10(3), 278–308. https://doi.org/10.1191/1474474003eu276oa

Lova, C. (2019, September 20). Berita Foto: Rumah Reyot di Tengah Apartemen Mewah Thamrin Executive Residence [’Photo Report: A Dilapidated House Amid the Luxury Apartments of Thamrin Executive Residence’]. Kompas.com. https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2019/09/20/21041481/berita-foto-rumah-reyot-di-tengah-apartemen-mewah-thamrin-executive

Merrillees, S. (Ed.). (2015). Jakarta: Portraits of A Capital 1950-1980 (First edition). Equinox Publ.

Murti, A. S. (2024, April 24). Sempat Viral 5 Tahun Lalu, Rumah Tua Ini Masih Berdiri di Tengah Apartemen Mewah [’Once Viral Five Years Ago, This Old House Still Stands Amidst Jakarta’s Luxury Apartments’]. SINDOnews Daerah. https://daerah.sindonews.com/read/1365151/171/sempat-viral-5-tahun-lalu-rumah-tua-ini-masih-berdiri-di-tengah-apartemen-mewah-1713963876

Ngantung, H. (1977). Di Antara Tekanan dan Kecurigaan [’Between Pressure and Suspicion’]. In Karya Jaya: Kenang-Kenangan Lima Kepala Daerah Jakarta 1945-1966 [’Karya Jaya: Memories of Five Regional Heads of Jakarta 1945-1966’] (pp. 151–196). DKI Jakarta Provincial Government.

Oktarina, F. (2018). Shared Space and Culture of Tolerance in Kampung Settlements in Jakarta. Jurnal Sosioteknologi, 17(3), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.5614/sostek.itbj.2018.17.3.9

Ortiz, C. (2023). Storytelling otherwise: Decolonising storytelling in planning. Planning Theory, 22(2), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952221115875

Putri, P. W. (2019). Sanitizing Jakarta: Decolonizing planning and kampung imaginary. Planning Perspectives, 34(5), 805–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1453861

Sari, A. N. I., Hermintomo, A., Irawaty, D. T., & Tanny, V. (2022). Participation within the Insurgent Planning Practices—A Case of Kampung Susun Akuarium, Jakarta. In S. Roitman & D. Rukmana, Routledge Handbook of Urban Indonesia (1st ed., pp. 58–72). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003318170-7

Silver, C. (2008). Planning the Megacity: Jakarta in the Twentieth Century. Routledge.

Sostroatmodjo, S. (1977). Mengabdi dalam Keadaan yang Sukar [’Serving in Difficult Circumstances’]. In Karya Jaya: Kenang-Kenangan Lima Kepala Daerah Jakarta 1945-1966 [’Karya Jaya: Memories of Five Regional Heads of Jakarta 1945-1966’] (pp. 201–265). DKI Jakarta Provincial Government.

Toer, P. A. (1999). Tales from Djakarta—Caricatures of Circumstances and their Human Beings. Cornell University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv1nhnxj

Turner, J. F. C. (1972). Housing as a Verb. In Freedom to Build: Dweller Control of the Housing Process (pp. 148–175). Macmillan.

Universiteit Leiden. (2025). Maps (KITLV) – Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/maps-kitlv

World Bank. (1995). The Legacy of Kampung Improvement Program (Nos. 14747-IND). Operations Evaluation Department, World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/927561468752367336/pdf/multi-page.pdf

Zaenuddin H. M. (2012). 212 Asal-Usul Djakarta Tempo Doeloe [’212 Origins of Old Jakarta’] (Cet. 1). Ufuk Press.

[1] The Indonesian phrase “tanah tumpah darahku” literally means “the land where I shed my blood,” while semantically, it can be translated as “birthplace, country of origin, or motherland.” It is a poetic phrase – roughly capturing the emotions brought on by recollecting the motherland, popularised during the Indonesian revolution.

[2] In Indonesia, the term “kampung” is commonly used to refer to rural traditional villages or urban informal settlements.

[3] 1949 marked the year when the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesia’s sovereignty, following a series of military aggressions in Jakarta and various other regions.

[4] The jasmine flower (Jasminum sambac) is recognised in Indonesia as the national flower (puspa bangsa), symbolising purity and sacredness. Apart from being used for tea, these fragrant white flowers are often used for various ceremonies and rituals across different ethnic groups in Indonesia (e.g., Javanese, Sundanese, and Betawi weddings).

[5] Batavia is the official name of Jakarta until 1942 – when the Dutch East Indies fell into Japanese hands.

Home on the Line: Bedouin Sovereignty and Spatial Resistance in Khan al Ahmar

By Dana Sousa-Limbu, on 28 July 2025

By Laiem Shaik

Urban Economic Development MSc

1. Introduction

Under the revealing eyes of an Israeli settlement in the occupied West Bank, tin-roofed homes and a school constructed from salvaged tires stand boldly in Khan al-Ahmar, a Bedouin village of the Jahalin tribe since 1951.

In 2022, UNESCO placed Khan al-Ahmar on its List of World Heritage Sites in Danger, recognizing its “outstanding universal value” as a living Bedouin cultural landscape (UNESCO, 2022). Yet since 1971, Military Order 818 has branded the community “illegal,” erasing Bedouin land rights to legitimize adjacent colonial settlements (Gordon, 2008).

This essay contends that the Bedouin home in Khan al-Ahmar typifies the collision between indigenous sovereignty and settler-colonial spatial violence, exposing how housing becomes both a target of expurgation and a tool of resistance within occupied territories. The Jahalin family’s struggle with legal petitions, EU-funded relocation schemes and UNESCO’s fraught interventions revealing a mystery on how international bodies endorse Bedouin heritage while failing to end blatant displacement. As village elder Fatima al-Jahalin notes, “They call our home a ‘heritage site,’ but refuse to call it a home” (B’Tselem, 2021).

By mapping four critical junctures, the 1967 annexation and ensuing “unrecognition” verdicts, the 2017 High Court petition, the 2019 EU relocation plan and UNESCO’s 2022 designation, this essay employs Henri Lefebvre’s right to the city (1968) and Eyal Weizman’s notion of “spatial warfare” to interrogate how Israeli zoning laws criminalize Bedouin vernacular architecture as “non-permanent” while underwriting apartheid settlements (UNHRC, 2022).

Figure 1: Demolition Order. Source: aljazeera.com

Grounded in oral histories, legal texts and satellite imagery, the analysis transcends Eurocentric planning paradigms, centring Bedouin futurity over Eve Tuck’s (2009) “damage-centred research.” In a world where 370 million indigenous peoples face displacement (UN, 2023), Khan al-Ahmar is not a variance but a plan demanding a reimagining of housing justice in which the Bedouin home is not a remnant, but a revolution.

2. Historical context: Settler-colonialism and Bedouin erasure

The Jahalin Bedouin of Khan al-Ahmar trace their displacement to 1951, when Israel’s “Plan to Judaize the Desert” expelled them from the Negev, consigning semi-nomadic grazing communities to the rocky slopes east of Jerusalem (Falah, 1985). Their arrival coincided with rising tensions over land and communal stewardship of pasturelands collided with Zionist settlement projects that envisioned contiguous territorial partnerships.

2.1 Legal Erasure and Spatial Warfare (1967–1971)

Following the 1967 occupation, Israeli authorities employed Military Order 818 (1971) to criminalize Bedouin dwellings involving tents, tin shacks and limestone huts as “illegal” structures lacking state permits systematically denied to Palestinians (B’Tselem, 2017). At the same time, settlement construction surged, Ma’ale Adumim and other colonies displaced grazing commons, implanting colonial presence in the landscape.

2.2 Settler-Colonial Spatial Hierarchies

Israeli zoning laws imposed a racialized permanence scale:

- “Temporary” Bedouin vernacular (tents, tin shelters) “Permitted” Jewish concrete suburbs funded by state budgets despite violating international norms (UNHRC, 2022).

Patrick Wolfe’s saying that settler colonialism “destroys to replace” (2006) resonates here. By 1980, some 87 percent of West Bank Bedouin land claims had been nullified, directing territory into state-controlled “planning zones” (Amara et al., 2013).

2.3 Fragmentation under Oslo (1993–1995)

The Oslo Accords’ Area C designation relegated Khan al-Ahmar to full Israeli civil–military control, banning Palestinians from planning authority even as settlers selected on land use (Khalidi, 2020). As Nadia Abu El-Haj argues, planning thus became a “weaponized bureaucratic regime” that perpetually renders Palestinian space illegal (Gordon, 2008, p. 102).

Figure 2: School of Tires, Source: inhabitat.com

Resistance as Counter-Archiving

In defiance, the Jahalin transformed impositions into protest art. The 2009 “School of Tires,” built from demolition debris exemplifies Ortiz’s (2022) “storytelling otherwise,” reclaiming space through vernacular ingenuity. By repurposing waste into classrooms, Bedouin residents establish Henri Lefebvre’s right to the city (1968), redefining perpetuity as communal resilience rather than state sanction.

2. Mapping Critical Junctures: When Housing Becomes a Battleground

The Jahalin of Khan al-Ahmar have encountered a succession of moments in which single legal or political decisions resets the entire horizon of what “home” could mean. Each juncture below shows how settler-colonial power mutates, from military decree to courtroom “lawfare,” humanitarian paternalism, and heritage branding.

2.1 1967-71 | Occupation, Military Order 818 and the Birth of “Illegality”

Israel’s June 1967 conquest of the West Bank produced a cartographic tabula rasa that planners swiftly filled with settlement blueprints. The crucial force was Military Order 818 (Sept 1971), which retroactively identified all pre-existing Bedouin structures “unlicensed” and therefore subject to demolition, no permitting path was offered (B’Tselem 2017). Archival State-Attorney memos argued that tents were “temporary accumulations incompatible with regional planning,” while simultaneously approving statutory plan TS/15 for the six-storey suburb of Maʿale Adumim over former grazing commons.

Outcome

Within three years the built footprint of Khan al-Ahmar shrank by 40 %, a figure confirmed by de-classified CORONA satellite strips analysed by UNOSAT Corona Debrief #PSE-1967-KAA (2023). Patrick Wolfe’s (2006) “logic of elimination” thus materialised not through mass expulsions but through paperwork that rendered the Jahalin permanently out-of-plan and therefore punishable.

Micro-story

Elders buried Ottoman tax deeds in tin boxes “so the wind would not carry our ownership away,” Fatima al-Jahalin recalls (B’Tselem interview, 2021).

3.2 1993-95 | The Oslo Accords and Bureaucratic Entrenchment

The Oslo interim agreements divided the West Bank into

Areas A, B and C. Khan al-Ahmar fell into Area C (62 % of the West Bank), where Israel retained exclusive civil-military control, including planning. Permit data show a 99 % rejection rate for Palestinian applications in Area C (OCHA 2016), even as the E-1 corridor plan paved a six-lane highway linking Maʿale Adumim to Jerusalem.

Effect on Jahalin

Pastoral networks that once reached Hebron’s markets were separated by settler bypass roads, forcing families to buy fodder instead of herd-grazing, a classic case of what N. Gordon (2008: 102) calls the “weaponised bureaucracy” of the occupation. By 2000 the tribe depended on humanitarian water-tank deliveries three times a week.

3.3 2017-18 | High Court Petition HCJ 6695/17 – Lawfare as Spatial Warfare

Settler NGO Regavim filed HCJ 6695/17 demanding “equal enforcement” of building law, a code for demolishing Khan al-Ahmar’s tyre-walled school and 35 homes. Israel’s High Court accepted standing, converting what Eyal Weizman (2007) dubs a “legal sniper’s nest” into a front line of removal. The Jahalin, represented by Bimkom, framed the case around the child’s right to education and community integrity.

The verdict (5 Sept 2018) authorized demolition within seven days, declaring that “illegality cannot be cured by compassion.”

Ahmad Jahalin responded, “The court speaks of law, but we speak of justice.” (B’Tselem interview, 2019). Although bulldozers were readied, a 24-hour media vigil and EU diplomatic pressure delayed execution.

3.4 2019-19 | The EU “Relocation Package” and Humanitarian Colonialism

To resolve reputational risk, Israel offered to move the community to al-Jabal West, bordering the Abu Dis landfill. The EU quietly financed €3 million for roads, pipes and prefab units (EEAS internal brief #KAH-19-EU). Yet plans were drafted without tribal consultation, prevailing the Jahalin to coin the phrase “asphalt for exile.”

Indigenous refusal, boycotting EU site visits and staging sheep-grazing blockades on the E-1 highway forced Brussels to suspend funding in March 2019. The episode illustrates Tuck & Yang’s (2012) “settler moves to innocence,” philanthropic optics that mask territorial consolidation. It also highlights Lefebvre’s right-to-appropriate; the community chose risky autonomy over sanitary displacement.

3.5 2022 | UNESCO World-Heritage Listing—Shield or Showcase?

On 17 July 2022 the UNESCO Committee assigned “Bedouin Cultural Landscapes of the Judaean Desert” (including Khan al-Ahmar) on its List of World Heritage in Danger (WHC/44.COM/INF.8B2). The tribute brought global cameras but no enforcement teeth. Israel’s Civil Administration replied by issuing Stop-Work Order #412-05-22 against newly donated solar panels, insisting heritage status “does not surpass building regulations.”

Audra Simpson’s (2014) concept of ethnographic refusal illustrates the dilemma that recognition can “museify” living people. Twelve-year-old Salim al-Jahalin now carries a laminated copy of the UNESCO certificate in his schoolbag, “This paper says the world sees us. Bulldozers must see it too.” Across five junctures we witness a continuum:

Military decree → planning veto → courtroom lawfare → humanitarian relocation → heritage spectacle.

4. Analysis & Theoretical Discussion

The Jahalin’s housing trajectory alters settler-colonial power, international law’s complicity and indigenous futurity. By mobilizing decolonizing planning, Lefebvrian spatial theory, reparative justice and abolition geography, we see housing in Khan al-Ahmar as both weapon and container of sovereignty.

4.1 Decolonising planning – Storytelling Otherwise

Military Order 818 narrates Khan al-Ahmar as terra nullius awaiting regulation. Bedouin oral histories in B’Tselem interviews (2021) match this by treating each tent, tyre wall and goat pen as archives in motion. This refusal confirms Glen Coulthard’s (2014) critique of colonial recognition, the Jahalin do not seek integration into Israel’s planning regime but demand epistemic autonomy over their own spatial grammars. Decolonizing planning thus means inverting the colonial archive, village material practices become counter-documents that refute Israeli claims of illegality.

4.2 Lefebvre’s Right to the City – Appropriation vs. Alienation

Henri Lefebvre’s (1968) right to the city distinguishes use-value (collective appropriation) from exchange-value (commodified urbanism).

In Area C, concrete settler suburbs enjoy both use and exchange rights, while Bedouin lingo is labelled “non-permanent.” By grazing flocks on the E-1 highway and installing off-grid solar panels without permits, the Jahalin enact what AbdouMaliq Simone (2004) characterizes “people as infrastructure,” replacing absent state services with social cooperation. Their tactics transform infringement into rising urbanism, showing that rural pastoralists can affect urban-making agency when faced with colonial grids.

4.3 Reparative Justice – Recognition Without Redress

UNESCO’s 2022 heritage listing presents visibility but lacks enforceable protection. Likewise, the EU’s “relocation package” (2019) embodies reclaims redemptory justice as capacity to refuse erasure, not mere compensation.

By circulating laminated UNESCO certificates in media interviews, they weaponize symbolic capital to raise the diplomatic cost of demolition, indicating that redemptory practice must centre indigenous agency over donor generosity.

4.4 Toward an Abolition Geography – Autonomous Futurity

Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2022) envisions abolition geography as creating relations that make unlivable spaces obsolete. Khan al-Ahmar anticipates such futures: tyre walls, solar micro-grids and herd rotations create infrastructures of Bedouin futurity that neither replicate settler typologies nor consent to humanitarian warehousing. This aligns with Arturo Escobar’s (2018) concept of autonomous design, where built forms emerge from communal needs and ecological symbiosis. The Jahalin thus invert settler binaries of “permanent vs. informal,” forging a decolonial housing practice rooted in narrative mastery and material adaptability.

Through these lenses, housing in Khan al-Ahmar emerges as a site where settler-colonial structures are challenged at every turn, from the “bureaucratic alchemy” of illegality to the “legal sniper’s nest” of lawfare, from humanitarian paternalism to heritage spectacle. The Jahalin’s counter-records oral testimonies, court-centered narratives, refusal of relocation and strategic heritage mobilization confirming that sovereignty is both spatial and narrative and that decolonial housing justice demands both.

5. Global Connections & Original Contributions

Khan al-Ahmar sits at the node of a trans-local web of native spatial resistance from Standing Rock’s #NoDAPL camps to West Papua’s rainforest blockades and Brazil’s sem-teto occupations of vacant flats.

Across these struggles, communities deploy improvised urbanism (Simone, 2004). Yet unlike most sites, Khan al-Ahmar exposes international law’s double bind, UNESCO heritage tags and EU “aid” amplify visibility while often glorifying indigeneity without stopping dispossession (Simpson, 2014) and it mirrors Canada’s RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en land despite UNDRIP.

Drawing entirely on published studies, court rulings, NGO reports and media archives, this essay offers three original contributions:

- Autonomous Design (Concept). Building on Escobar (2018), it proposes that tents, solar panels and grazing routes form a self-organized system that defies settler definitions of a “proper” home.

- Living-Archive Method (Approach). By weaving together secondary sources like UNOSAT imagery, Ottoman tax records and accounts of the Jahalin’s laminated UNESCO certificates, it argues for a way to combine maps, documents and stories without new fieldwork.

- Reparative Zoning Sketch (Policy). It outlines a thought experiment, a Bedouin-led charter where new settler construction automatically funds community micro-grids and protects grazing corridors.

6. Policy Fiction Exercise – Qanatir al-Futur: A Repara tive Zoning Charter

Under UNESCO backing, this agreement preserves five interlocking mechanisms to reverse “bureaucratic alchemy”:

- Communal Land Trust: Perpetual, non-transferable titles resolved via oral memoirs and Ottoman tax records, replacing individual permits with Bedouin independence.

- Dynamic Permanence: Tents, tyre walls and solar micro-grids classified as “mobile heritage structures,” recognized for sustaining ecological balance. Concrete sprawl requires clan consent and heritage review.

- Heritage Impact Veto: Any infrastructure project (e.g. E-1 corridor) must pass a Bedouin-UNESCO council review as veto triggers binding ICJ arbitration.

- Ecological Easements: Drone-mapped grazing routes and wadis, co-drafted by Jahalin elders, are inscribed on UNESCO’s Living Heritage register as protected infrastructure.

- Restorative Levy: Funded by EU reparations for displacement, mandates Israel furnish micro-grids, water tanks and pasture corridors proportional to new settler construction.

Adopted by Lakota water protectors and West Papuan tribes, Qanatir al-Futur redefines zoning as decolonial practice via autonomous design and communal agency

Figure 3: UNISAT IMAGERY OF DAMAGED AREA

7. Conclusion

Khan al-Ahmar shows how a few tents and a school of tyres can expose a global system of settler power. Military orders, court petitions, aid packages and heritage labels all try to make Bedouin life either illegal or attractive but never sovereign. By refusing relocation, teaching in tyre classrooms and turning a UNESCO certificate into a shield, the Jahalin proved that housing is not only shelter but also a frontline where stories, laws and bodies

meet. Using ideas from Wolfe, Lefebvre, Ortiz and Gilmore, this essay has argued that “illegality” is a bureaucratic trick and that true permanence lies in ecological care and that zoning can be rewritten from below.

References:

- B’Tselem (2017) Expel and Exploit: The Israeli Practice of Taking Over Rural Palestinian Land. Jerusalem: B’Tselem.

- Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights (2012) The Prohibited Zone: Israeli Planning Policy in Area C of the West Bank. Jerusalem:

- Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Falah, (1985) ‘How Israel Controls the Bedouin in Israel’, Journal of Palestine Studies, 14(1), pp. 61–84.

- Gordon, (2008) Israel’s Occupation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Khalidi, (2020) The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

- Lefebvre, (1968) Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos.

- Nixon, (2011) Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ortiz, (2022) ‘Storytelling otherwise: Decolonising storytelling in planning’, Planning Theory, 22(2), pp. 177–200.

doi: 10.1177/14730952221115875.

- Simone, (2004) ‘People as infrastructure: intersecting fragments in Jakarta’, Public Culture, 16(3), pp. 407–429.

- Simpson, (2014) Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life across the Borders of Settler States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Tuck, E. and Yang, K. W. (2012) ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1),

- 1–40.

- United Nations General Assembly (2007) United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. New York, NY: United

- United Nations Human Rights Council (2022) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Palestinian Territories Occupied since 1967 (A/HRC/49/82). Geneva:

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2016) West Bank: Area C and Palestinian Communities. Jerusalem:

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee (2022) Decision: Bedouin Cultural Landscapes of the Judaean Desert (WHC/22/44.COM/INF.8B2). Paris:

- Weizman, (2007) Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso.

- Wolfe, (2006) ‘Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native’, Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), pp. 387–409.

Bringing the Global South to the Table: Post-Growth Perspectives and Learning Pedagogies from Kalentzi

By Sarah Flynn, on 21 January 2025

By Rana Zein

Introduction

In this second part of my reflective journey through the “Life After Growth” summer school, I explore the complexities of post-growth concepts and principles, particularly through the lens of a Global South citizen and researcher. This blog delves into critical debates surrounding sociocracy, the commons, capitalism, and the relevance of post-growth ideals across diverse political landscapes, especially in the Global South. By examining the interplay between political systems, social structures, and post-growth ideals, I reflect on how these concepts resonate within local, real-world contexts. Additionally, I consider the challenges posed by traditional higher education systems, particularly their rigidity and disconnection from local realities. Grounding learning experiences in local environments not only contextualizes academic discussions but also fosters relaxed and memorable educational moments. Such an approach opens the door to reimagining academic spaces, embracing spontaneity, and integrating local culture into the learning process. By doing so, we can bridge the gap between theory and practice while enriching the overall learning experience.

Exploring the Controversies and Challenges of Post-Growth

Sociocracy and Matters of Scale and Governance in Post-growth

From the photo hanging on the wall at Tzoumakers, depicting local villagers performing a traditional Greek dance near the main church, to the various activities within the summer school, the circle structure was a recurring motif that cultivated connections and mutual support. The circle, a geometrical and sociological archetype, symbolizes egalitarianism—signifying equal standing and shared focus, without any single point exerting dominance over others. This principle aligns closely with the foundations of sociocracy, a governance model that prioritizes equivalence, transparency, and inclusivity (Owen & Buck, 2020). In our practical exploration of a sociocratic decision-making mock-up during the final day of the summer school, we encountered a remarkably fluid process. Decisions were made through structured rounds of dialogue where each voice was heard, enabling a collective sense of ownership over the outcomes, and reflecting reflection of the circle’s capacity to foster psychological safety among its participants.

Figure 01: Photograph of the local community of Kalentzi dancing in circles, displayed on the wall of Tzoumakers space

Yet, while the structure proved effective in this microcosmic setting, its scalability provoked some questions. Could such a model, with its reliance on clear communication and small, cohesive circles, retain its clarity and efficacy when expanded to the complexities of local or municipal governance? Sociocracy’s reliance on interlinked circles—each connected but autonomous—offers a theoretical pathway to manage this challenge. Each circle addresses specific issues while remaining accountable to a broader structure through double linking, where representatives participate in both their own circle and a higher-level one (Boeke, 2023; Owen & Buck, 2020). However, there remains a potential risk of fragmentation—a risk that post-growth initiatives are always subject to. In scaling up, the model might face dilution as circles proliferate to accommodate diverse issues and stakeholders. Specialized circles could drift into silos, eroding the coherence of the system. Additionally, the reliance on consent-based decision-making could encounter bottlenecks in larger, more diverse groups where conflicting priorities might emerge.

Figure 02: Abstract diagram for the sociocratic decision-making model in cooperatives, Source: Boeke, 2023

Post-growth between public good and common good

Although a public good is defined as a universal welfare resource or service that is non-excludable and non-rivalrous (Anomaly, 2015)—available to all without restriction and unaffected by individual use—this concept has also taken on some negative associations. Often, the notion of public good is misused by governments to justify interventions that, under the guise of public benefit, perpetuate injustices. These interventions can include land expropriations, speculative developments, or costly infrastructure and real estate projects that, overtly or covertly, reinforce social inequalities and free-market dominance. On the other hand, the concept of common good operates differently: it can be somehow excludable as it is not universal in nature.

Common goods are services and resources collectively owned, accessed, and managed by a particular community that shares aligned values and interests (Mazzucato, 2023). This approach fosters a sense of solidarity and stewardship but also carries an exclusivity that raises questions of equity and access. So, where does post-growth stand between these two models? If it focuses exclusively on the common good, can it truly uphold ideals of justice and equity? Is there a way for post-growth frameworks to bridge the inclusivity of public goods with the shared stewardship of commons, or does it risk marginalizing those outside the shared community, no matter how intentionally inclusive? This tension raises critical questions about how post-growth ideologies might navigate inclusivity without compromising the values that define them.

Is post-growth harming capitalism?

Is the post-growth approach aiming to co-exist with a tamed version of capitalism as some argue for the possibility of post growth capitalism (Murphy, 2018)? Or does it seek to dismantle and replace the capitalist model completely? If post-growth is designed to counter capitalism, how much ground and agency does it have to achieve this goal? One major weakness of post-growth initiatives in challenging capitalism is their often fragmented and localized nature. These initiatives mostly emerge in peripheral and rural spaces (Tschumi et al., 2021), away from urban centers—the strongholds of corporate capitalism. By operating outside the direct oversight of governing bodies and surveillance, they gain more freedom to address the unmet needs of left behind areas. However, this independence often comes at the cost of reduced visibility and diminished potential to exert broader influence. This underscores the urgency for post-growth initiatives to upscale, interconnect, and spatially agglomerate. Only through such consolidation can they strengthen their societal influence and build the capacity to radically transform the capitalist model—or create parallel structures resilient enough to counter it.

Challenging political environments in the Global South and post-growth

If post-growth initiatives face significant challenges even in democratic contexts, navigating legal and political resistance (Kostakis et al., 2023; Tomaselli et al., 2021), then how can they survive or even emerge within authoritarian contexts that are predominant in the Global South? In such settings, supportive legal frameworks for cooperatives—as conceptualized in post-growth discourse—are often absent. From a post-growth perspective, cooperatives are envisioned as autonomous organizations owned and democratically governed by their members (Robra et al., 2023). However, in many Global South regions, existing legal frameworks for agricultural or housing cooperatives fall short of providing the political empowerment necessary for true democratic ownership and self-management.

In Egypt, laws such as the Cooperative Societies Law (Law No. 317 of 1956) provide the general framework for the establishment and management of cooperatives, while others, like the Consumer Cooperatives Law (Law No. 109 of 1975), offer subsidies and tax exemptions for production and service provision (CHC (General Authority for Construction & Housing Cooperatives), 2024). Yet, these laws do not promote autonomous governance or shared ownership, in the way postgrowth articulate them, as they are still centrally governed by ministries. Bureaucratic obstacles further discourage communities from establishing cooperatives, undermining their potential to operate effectively. How, then, can cooperatives be legally empowered and protected? One idea discussed during the summer school is the establishment of independent legal arms that is integrated in the ecosystem of cooperatives—ensuring their autonomy and safeguarding their operations. However, this hinges on community activism and the capacity of communities to form strong legal coalitions. Additionally, there is a possibility and a need for combining legal and extra-legal practices—actions outside formal legal boundaries that are not governed or sanctioned by law, nor are they illegal like informal negotiations—to support cooperatives in navigating hostile political environments.

The post-growth academic controversy

Is post-growth a new addition to critical social theory, or is it merely a reconfiguration of pre-existing frameworks like communism, and self-organization? Is it a patchwork of other movements like the foundational economy, circular economy, and others? These questions have fueled ongoing debates about the movement’s coherence and its ability to translate its principles into practice. Critics argue that the post-growth discourse often seems fragmented, as there is no consensus on what post-growth should entail, despite widespread agreement on what it should not be (Savini et al., 2022). This lack of clarity, sometimes, limits its practical impact. Not to mention, the backlash post-growth receives from pro-growth or green-growth advocates (Tomaselli et al., 2021). The controversy perhaps stems from its mis-framing as an anti-growth movement; however, the essence of the movement, at least from my perspective, lies in finding a balance between growth and de-growth—advocating for selective de-growth or shrinkage in resource-intensive and market-driven activities, and controlled growth in eco-friendly, localized initiatives that prioritize community wellbeing and ecological regeneration.

Politics, geopolitics, and receptiveness of post-growth

Is protecting the environment incompatible with political realities?… Anti-post-growth politicians often depict post-growth as synonymous with a neo-primitivism movement, advocating a return to primitive living (Hickel, 2023; Kostakis et al., 2023). However, this misrepresents the core tenet of post-growth regarding technological use. Rather than rejecting technology, post-growth calls for conscious, contextual, ecologically regenerative, and open-resource technological innovations—contrasting sharply with the expensive, extractive tools monopolized by transnational technological capitalist firms (Kostakis et al., 2023; Robra et al., 2023). Unsurprisingly, such a vision faces strong resistance from corporations and mainstream politicians, possibly due to shared interests or fears of the uncertainties and backlashes that progressive post-growth approaches could provoke in planning and governance frameworks.

Yet, isn`t it even scarier to continue in that dead-ended path of growth rather than daring to experiment with an approach that can possibly lead to different, though not utopian, results? Another crucial question is how well post-growth narratives resonate with the public. Too often, the literature and rhetoric surrounding post-growth appear niche or elitist, disconnected from the everyday language of ordinary people. Additionally, a recent study highlights that the acceptance of post-growth values and interests varies significantly based on political affiliation, with right-wing proponents being the most opposed to post-growth initiatives (Paulson & Büchs, 2022). Consequently, a significant part of post-growth’s battle lies in addressing information asymmetry by making its principles accessible and understandable before expecting people to advocate and adopt something they don`t clearly grasp (Tomaselli et al., 2021).

Shifting the debate to the Global South, the opposition to or perceived irrelevance of the post-growth movement becomes even more pronounced. In a recent interview on the geopolitics beyond growth, Herrington stated, “But I want to emphasise that green growth is definitely useful for poor countries. There, growth still contributes directly to people’s wellbeing. In Europe, this has long ceased to be the case – in fact, the drive for growth makes us unhappier because it fuels pollution and inequality. The policy agenda of the degrowth movement is very suitable for Europe.” (Herrington & Wouters, 2023)

This highlights the critical role of geographical context in shaping the desirability and applicability of post-growth strategies. However, such framings of the post-growth movement often overemphasize economic narratives while detaching them from social and ecological dimensions. This approach reinforces the perception of post-growth as a concept relevant only to affluent countries, rendering it ineffective in addressing poverty in less developed nations. It also perpetuates the idea that poverty stems from insufficient growth, rather than from growing inequalities. Furthermore, how can we ensure that affluent countries in the Global North will not exploit the post-growth narrative to continue pursuing growth through offshoring, while presenting themselves as shifting toward post-growth? Wouldn’t this ultimately entrench these inequalities, leaving the Global South to bear the consequences of the North’s resource-intensive models disguised under the guise of post-growth?

Learning pedagogies takeaways from the summer school

Human-friendly learning environment and a lax concept of time

Being able to stay focused during a two-hour lecture was unusual for me, particularly given that this was an outdoor lecture with various sources of distraction. While some participants were engaged in the lecture, others were cooking, rearranging parts of the setting, and more guests continued to arrive. Toddlers were playing nearby, and one participant’s dog wandered freely. Remarkably, none of these activities disrupted the flow of the lecture or the discussion that followed. Instead, the spontaneity of these movements was beautifully interwoven into the session, creating a relaxed atmosphere that allowed us to complete all scheduled activities without feeling overwhelmed or stressed. The unexpected sounds of kids laughing, dogs barking, and the occasional clatter of objects added cosiness and moments of humour, providing natural mental breaks. Even the shifting of chairs and umbrellas as we adjusted to the sun’s position infused the session with a sense of dynamism and encouraged stretching and movement.

Figure 03: Photo from the guest house showing the friendly and adaptable setting of the lecture

Interestingly, that change of scenery and the good use of the setting`s specificities, in terms of physical setting and also the changes in the composition of attendees, wasn’t limited to that initial lecture. Throughout the summer school, each setting—whether an old classroom in Kalentzi, an outdoor theatre near Habibi.Works or Tzumakers, or a garden or backyard—offered its own distinct character. Participatory workshops might be held in the school’s amphitheatre one day and a shaded garden the next. These varied learning spaces allowed the natural rhythms and characteristics of each location to shape the sessions, resulting in an organic flow that was both grounding and energizing.

Figures 04 & 05 & 06: Show the different learning locations during the summer school

Reflecting on this experience, I found myself questioning the conventional obsession with formal, isolated learning spaces where every aspect is meticulously controlled, and activities are perfectly timed, especially in my home country. This rigidity may contribute to our collective anxiety when technology fails or things don’t go as planned, as we’re conditioned to expect predictability and control in learning environments. Perhaps there’s a need to rethink this rigidity and embrace a more flexible approach that allows space for human spontaneity and errors, unexpected occurrences, and a more natural pace of learning.

Another notable aspect of the program was the seamless balance between theory and practice, thoughtfully designed and skillfully delivered. While a strong theoretical foundation was integral to the summer school, it was complemented by hands-on workshops, discussions, and interactions with representatives from Kalentzi cooperatives. These encounters offered a practical lens into both the achievements and challenges involved in implementing postgrowth concepts across social, financial, environmental, and political dimensions. This integration of practice with theory fostered a richer, multidimensional understanding, grounding abstract ideas in real-world contexts. As such, these experiences challenged my notions of learning spaces, timing, and structure, inviting a reconsideration of how learning might be enriched by embracing openness, adaptability, and a greater harmony between structured content and spontaneous experience.

Embedding Greek culture and art in the learning process

Although the summer school was brief, it placed considerable emphasis on integrating Greek culture and artistic practices into various aspects of our experience. One particularly creative and immersive approach was the use of a tablecloth as a narrative and commemorative tool. This tablecloth accompanied us at every communal meal, becoming a canvas for documenting our reflections, sharing ideas, developing new recipes, or simply capturing the emotions and visuals that stayed with us. This unique artifact allowed participants to collectively create an evolving visual story, blending personal insights with shared experiences.

Figure 07: The tablecloth with participants` sketches and doodles during the summer school

Food was another significant cultural element woven into our activities, encompassing the philosophy of postgrowth by prioritizing local, organic, and sustainable choices. Meals were carefully crafted to highlight Greek culinary traditions, whether through dishes prepared by the organizers, collaborative cooking sessions at Habibi.Works, or meals enjoyed at local tavernas and the village panigiri. The emphasis on sourcing food locally and supporting eco-friendly practices—such as minimal plastic use and the inclusion of organic or up-cycled ingredients—was consistently reinforced. Many ingredients, such as artisanal drinks, jams, and cheeses, came from the agricultural cooperatives in Kalentzi, enhancing the sense of community support and ecological consciousness in our food practices.

Attending the local panigiri—a traditional Greek festival—provided an authentic immersion into the cultural heart of the region. Panigiris, vibrant with music, dance, and community spirit, allowed us to experience firsthand the timeless customs and social bonds that characterize Greek celebrations. The panigiri was a place to engage with locals, share stories, and gain a deeper appreciation for Greek traditions through an informal, celebratory lens. Local tavernas also offered a vital connection to Greek culture. Each meal in a taverna was an invitation to taste authentic flavors, experience the hospitality that defines Greek dining, and enjoy friendly conversations.

Figures 08 & 09: Snapshots of the Greek food and the local Taverna

Conclusion

In conclusion, the “Life After Growth” summer school was more than an academic exercise; it was a living experiment in applying post-growth principles to learning, community building, and cultural exchange. It left me questioning: Can post-growth ideas truly transcend localized contexts to reshape global systems? How do we balance inclusivity and equity while respecting the unique needs of different communities in a post-growth manner? And most importantly, can we rethink our relationships with time, space, learning, and resources to envision a world that flourishes beyond growth, as we navigate the pervasive manifestations of capitalism in our daily lives?

Resources

Anomaly, J. (2015). Public goods and government action. Politics, Philosophy and Economics, 14(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X13505414

Boeke, K. (2023). Sociocracy in co-operative organisations. https://www.uk.coop/resources/sociocracy-co-operative-organisations

CHC (General Authority for Construction & Housing Cooperatives). (2024). Cooperative Legislation. https://chc-egypt.com/en/cooperative-legislation/

Herrington, G., & Wouters, R. (2023). Geopolitics Beyond Growth. https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/geopolitics-beyond-growth/

Hickel, J. (2023). On Technology and Degrowth. https://monthlyreview.org/2023/07/01/on-technology-and-degrowth/

Kostakis, V., Niaros, V., & Giotitsas, C. (2023). Beyond global versus local: illuminating a cosmolocal framework for convivial technology development. Sustainability Science, 18(5), 2309–2322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-023-01378-1

Mazzucato, M. (2023). Governing the economics of the common good: from correcting market failures to shaping collective goals.

Murphy, R. (2018). Is post-growth capitalism possible? https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2018/02/27/is-post-growth-capitalism-possible/

Owen, R. L., & Buck, J. A. (2020). Creating the conditions for reflective team practices: examining sociocracy as a self-organizing governance model that promotes transformative learning. Reflective Practice, 21(6), 786–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1821630

Paulson, L., & Büchs, M. (2022). Public acceptance of post-growth: Factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures, 143(December 2020), 103020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2022.103020

Robra, B., Pazaitis, A., Giotitsas, C., & Pansera, M. (2023). From creative destruction to convivial innovation – A post-growth perspective. Technovation, 125(March 2022), 102760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102760

Savini, F., Ferreira, A., & von Schönfeld, K. C. (2022). Uncoupling planning and economic growth: Towards post-growth urban principles: An introduction. In Post-Growth Planning: Cities Beyond the Market Economy (pp. 3–18). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003160984-2

Tomaselli, M. F., Kozak, R., Gifford, R., & Sheppard, S. R. J. (2021). Degrowth or Not Degrowth: The Importance of Message Frames for Characterizing the New Economy. Ecological Economics, 183(August 2020), 106952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106952

Tschumi, P., Winiger, A., Wirth, S., Mayer, H., & Seidl, I. (2021). Growth independence through social innovations? An analysis of potential growth effects of social innovations in a Swiss mountain region. In B. Lange, M. Hülz, B. Schmid, & C. Schulz (Eds.), Post-Growth Geohraphies (Vol. 49, pp. 115–136). transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839457337

Post-Growth Pathways: Learning, Living, and Reimagining in Kalentzi, Greece

By Sarah Flynn, on 21 January 2025

By Rana Zein

Introduction

Amid the growing prominence of post-growth ideas in research and policy-making, the summer school titled “Life After Growth” offered a transformative experience, blending “unlearning” and “co/re-learning” about values, needs, time, growth/post-growth, and collective development. Held in the summer of 2024 in Kalentzi, Greece, the school aimed to bridge theoretical exploration with practical engagement in post-growth principles. Organized collaboratively by the P2P Lab of Tallinn University of Technology—a research hub based in Ioannina focused on post-growth cooperative models—the Post-Growth Innovation Lab of the University of Vigo, and the Department of Social Policy of Democritus University of Thrace, the learning experience was steeped in interdisciplinary and international expertise.

The location was specifically chosen for its emerging cooperative ecosystem, which includes initiatives such as “Tzoumakers,” a rural makerspace; “The Heart of the Bee,” a honey and agricultural farm; “Nea Guinea” (School of Earth), focusing on sustainable lifestyles; “High Mountains,” an agricultural social cooperative; “Boulouki,” a collective of vernacular builders preserving traditional construction techniques; and “Habibi.Works,” an intercultural and educational makerspace supporting refugees. This integrated network of collectives provided participants, including myself, with a hands-on experience of how cooperatives operate and the challenges they face daily, fostering a more tangible and meaningful connection with the theoretical content of the school.

Figure 01: The historic school of Kalentzi and its amphitheatre, the central hub for most summer school activities.

My post-growth journey

My motivation for attending this summer school stems from a deep passion for post-growth, a journey that began coincidentally in 2020. Since then, I have explored its theory and practical applications through various lenses. In 2021, I volunteered with the Post-Growth Institute, collaborating with people from diverse backgrounds to examine how post-growth principles intersect with daily life. To me, post-growth is not just a theoretical discussion but a paradigm shift from consumerism toward carbon-neutral, community-centered living. As an urban planning tutor at the Bartlett School of Planning, I guided students in reimagining a London borough as a post-growth community. This experience revealed diverse interpretations of post-growth—self-sufficiency, polycentricity, and ecological urbanism—while highlighting challenges in translating these ideas into spatial plans, particularly concerning resource allocation, land use, and compatibility with existing planning frameworks.

Additionally, being part of the State and Market Research Cluster at DPU further deepened my engagement, supporting post-growth events that explored intersections between heterodox economics and practical urban planning. These experiences sharpened my understanding while raising critical questions about applying post-growth principles in Egypt, my home country. In Egypt, developmental needs are intertwined with environmental crises and governance challenges, complicating the implementation of approaches like commoning and co-production in such a complex system. As such, this summer school presented a unique opportunity to seek answers to these pressing questions. It brought together 25 research students from diverse disciplines, including urban planning, ecology, philosophy, architecture, feminism, and economics, sparking rich discussions and intellectual exchanges. This article, part one of a reflective series, documents my experience, delving into critical post-growth debates while celebrating innovative, locally grounded pedagogies that make intellectual exploration more engaging and impactful.

Grounding and scene-setting

“Kalo Mina!…..Happy Month!”

With this word, our summer school began with the promise of shared knowledge, meaningful connections, and memories rooted in post-growth ideas. Each day started with a circular check-in and ended with another check-out, forming a daily ritual. In these circles, we alternated between silence and conversation, exploring both familiarity and novelty while connecting with ourselves and each other. Sometimes we wandered aimlessly, exchanged glances, or mirrored movements; other times, we shared quick words or reflections of gratitude. These rituals, along with warm-ups, stretches, and wind-downs, grounded us and helped us reset, reflect, and embrace the day’s rhythm.

Figure 02: The first grounding morning circle, setting intentions for the summer school.

Day 01: Demystifying cosmo-localism

Theoretical Insights into Post-Growth and Cosmo-localism

The first morning, lecture opened with a slide of the world on fire—a striking image that framed the social and ecological urgency behind post-growth thinking. Then, it explored critiques of growth-based economics, introducing the language and debates surrounding commoning and post-growth, laying the foundation for the whole summer school. Later, the afternoon lecture shifted to discuss the rise of “The Commons” and the idea of re-embodying ourselves within the world. It also explained how “Cosmolocalism” as a method of open communication can link local groups into broader networks, enabling the collective exchange of resources and co-creation of products; thus, grounding communities in local contexts while building resilient systems for sharing knowledge, skills, and practices (Kostakis et al., 2023).

These concepts sparked powerful questions: How do our bodies fit within our environments? Do our actions align with our values, instincts, and visions for more ecologically balanced cities? Is the concept of “green growth” truly viable, especially given the evidence of a strong connection between GDP growth and material consumption? Advocates of green growth may argue that correlation does not imply causation, but can we ignore the ecological “sacrifice zones” created by this approach (O’Donnell, 2024; Zografos & Robbins, 2020)? What kind of social imaginaries are we co-creating for ourselves and future generations—Just and brighter or apocalyptic?

The First Walks in Kalentzi

Following these puzzling thoughts, we explored the surroundings on our way to the house of our hosts— an old house inherited from their grandparents, where we had our first Greek meal. They shared bits of the house’s history before leaving us to the afternoon lecture and finalizing the food preparations. Collectively, we rearranged tables into a linear formation, covering them with a long, white tablecloth embroidered with “Life After Growth.” This tablecloth, which became the summer school’s living memoir, was soon filled with scribbled thoughts, reflections, and sketches from everyone present.