“Who was this woman and why did she have her back to me?”

By Krisztina Lackoi, on 4 July 2012

Last month 8 history and history of art students from City and Islington College attended a workshop at UCL Art Museum based on some of the images of African and Asian sitters who appear in the UCL collections. (For a background of the Drawing Over the Colour Line project, read organiser Gemma Romain’s guest blog here.) Read what some of the students thought and felt about the images and the workshop day.

Aimee Nimr, A study of a female figure, between 1918 and 1919, UCL Art Museum SDC6555

by Siobhan Carla

Looking at these sketches makes me think about my heritage a lot, which is oddly why I chose to base this blog on Aimee Nimr. It was mostly b ecause it was a lot different to what I had seen earlier as it was of a European woman, it had a different feel to it and made me have a different outlook upon it. The woman almost looks scared, maybe insecure and slightly vulnerable which makes me feel sad and, in a way, worried about her. This was portrayed by her slightly arched shoulders and her back to the audience, this made it very mysterious too. Who was this woman and why did she have her back to me? Read the full post here.

ecause it was a lot different to what I had seen earlier as it was of a European woman, it had a different feel to it and made me have a different outlook upon it. The woman almost looks scared, maybe insecure and slightly vulnerable which makes me feel sad and, in a way, worried about her. This was portrayed by her slightly arched shoulders and her back to the audience, this made it very mysterious too. Who was this woman and why did she have her back to me? Read the full post here.

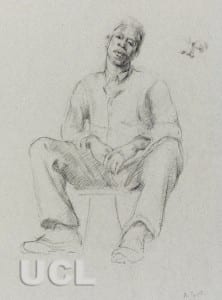

Martin E. Burniston, Study of a male nude, standing to right, with right arm resting on hip, UCL Art Museum, 6271 and John Farleigh, Ecclesiastes and the Black Girl, UCL Art Museum, SPC7331

by Sogol Afshar

I personally found the nude drawings very interesting, as I am more familiar with this style of drawing and sketching, which are mostly drawn from real  life objects or people. However, I believe life drawing is a westernised technique. And the sitter/model could be anyone from any type of background or race. Therefore, unfortunately I couldn’t relate to the drawings. For example, Study of a male nude by Martin Burniston shows an African nude male standing to the right with his right arm resting on his hip, which is a typical, simple pose for a life drawing model. By finding more about Harlem Renaissance and the black movement, the previous paintings depicted civilised African Americans who are in power of their own identity. Whereas, in my opinion the life drawings didn’t carry any sense of empowerment or civilisation as any artist could ask any black man or woman to pose for them. Read the full post here.

life objects or people. However, I believe life drawing is a westernised technique. And the sitter/model could be anyone from any type of background or race. Therefore, unfortunately I couldn’t relate to the drawings. For example, Study of a male nude by Martin Burniston shows an African nude male standing to the right with his right arm resting on his hip, which is a typical, simple pose for a life drawing model. By finding more about Harlem Renaissance and the black movement, the previous paintings depicted civilised African Americans who are in power of their own identity. Whereas, in my opinion the life drawings didn’t carry any sense of empowerment or civilisation as any artist could ask any black man or woman to pose for them. Read the full post here.

Aimee Nimr, A study of a female figure, between 1918 and 1919, UCL Art Museum SDC6555 and Martin E. Burniston, Study of a male nude, standing to right, with right arm resting on hip, UCL Art Museum, 6271

by Lily Evans-Hill

The female figure studies pose embodies a vulnerable position. Her back faces the onlooker and her arms are folded behind her back and we can imagine her armor-less bare front. However, there is a balance of her passiveness as you can see her bold stare. The woman’s face is important in restoring her domination of the page. Her stare suggests she is pondering the scene in curiosity and not in fear. Her pose reminds us of a masculine stance, she has stationed herself with her feet firmly on the ground. Her muscles appear well defined and masculine, the aesthetic that lends to the idea of the woman being dominative. Read the full post here.

Close

Close