Sculpture and photography: Edward Allington, Euridike 1986

By Nina Pearlman, on 24 April 2019

Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture at UCL Art Museum till 7th June 2019. Part of UCL’s Year of Sculpture.

‘The exhibition is a beautiful teaser for what one hopes might one day be a larger retrospective’. The full review in Apollo Magazine can be viewed here.

Edward Allington, Euridike (1986), photographed in UCL Art Museum, 2012, by Heini Schneebeli © Heini Schneebeli and the artist’s estate

For Edward Allington photography was part and parcel of making, experiencing and understanding sculpture. He wasn’t alone in this. Sculptors worked with photography in the late 19th century and the bond between the two mediums dates back even further, to the birth of photography itself. Artists like Rodin and Brancusi experimented with the new medium of photography early on, documenting their practice, using it to communicate with their audiences and collectors, as well as exploring juxtapositions of works in the studio. Photographing classical sculpture was integral to the work of photography pioneers such as Henry Fox Talbot and Roger Fenton, whose work influenced the type of photography and lighting favoured by art historians and museum registrars.

Combining sculpture and photography for Allington would have also been inspired by the work of American artists in the second half of the 20th century such as the architectural interventions of Gordon Matta Clark – comprising of carved or sliced derelict suburban buildings, or the landscape interventions of Robert Smithson – undertaken in remote and uninhabited areas. Iconic site-specific interventions by these artists, into spaces and places that already exist, such as Matta Clark’s Splitting (1974) and Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) would have reached Allington’s attention by way of a documentary photograph. It was the photograph that travelled and reached audiences far and wide. It was also the photograph that became the object of consumption. Allington, recognising that sculpture ultimately spends much of its life in storage or inaccessible, and therefore its visibility is mediated through photography, was determined to see photography become an integral part of his sculptural practice.

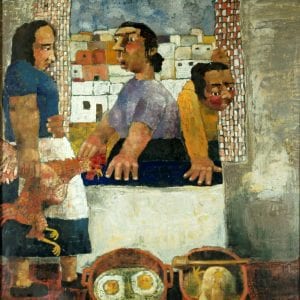

When Allington conceived of his small bronzes in the mid-1980s he was preoccupied with 19th century European parameters of scale – namely something small enough but with sufficient presence to occupy a space in a vitrine or a study of a connoisseur. He found inspiration in the small surrealist sculptures of Alberto Giacometti of the 1930s, that drew on the surrealist principles of assemblage, and produced a set of component forms which he proceeded to assemble into sculptures. These component forms, drew on Giacometti’s aesthetic language which itself assimilated African and Oceanic influences. Giacometti’s series of Disagreeable Objects (1931) often included phallic sensibilities and spikes. Echoes of this language are evident in Allington’s Euridke, 1986, pictured here.

Of the small bronzes Allington had written that it had been his intention to allow the small bronzes to ‘find their place in the world with the minimum positioning needed to clarify my intentions’ [1]. By this we can assume he meant, simply placing them in aforementioned environments. However, as he became interested in increasing the scale of these works and formalising their position, giving rise to his own iconic series Pictured Bronzes, Allington embarked on one of the most significant collaborations of his career – with Edward Woodman. ‘Working with a photographer, […Woodman], I contrived to remove an ornament or object from the setting, and replace it with the bronze, which was then photographed. The completed work comprises the bronze, displayed upon a white shelf in the gallery, with a white framed photograph of the work in its ideal setting. Thus pictured, the bronze is complete’ [2]. The exhibition features a film in which visitors can see Allington and Woodman’s collaborative working method [3]

A recurring theme for Allington was sculpture’s capacity to subvert its surroundings and for sculpture’s capacity to change as a result of its placing. He was interested in casting sculpture in a role that animated its environment and everything in it. He maintained that everywhere there is a space in which sculptures cohabit and interact with other things and that most sculptures are made with ideal settings in mind yet are more likely to exist in storage, a home, an institution or a photograph. The reference to the photograph was a nod at once to the conceptual work of the 1970s mentioned above, but also to the classical sculpture of ancient Greece, known to us only through descriptions in Greek texts and the Roman copies inspired by these descriptions. The copies were then subsequently photographed and enjoyed wide circulation by the European elite classes who embarked on Grand Tours to sites of cultural significance from the mid-17th century until the Napoleonic wars of the end of the 18th century.

Edward Allington, Euridike (1986), bronze, exhibition installation UCL Art Museum, Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture, 2019. Photograph: Mary Hinkley

UCL Art Museum is not a white cube. Far from it. Its form is that of a traditional print room, with cabinets filled with prints and drawings that date back to the 15th century and extend all the way to the 21st. Scattered around are examples of sculptures, various copies used historically at the Slade School of Fine art to aid instruction and training of young artists as well as Victorian busts. The museum walls are yellow, Farrow & Ball Print Room Yellow, to be precise, and these are populated with plaster models by the acclaimed British neo-classicist sculptor John Flaxman, revered by Allington. These walls are not a fit for Pictured Bronzes, works that are in dialogue with a ‘white cube’ aesthetic.

Allington was interested in Flaxman for many reasons. A son of the industrial revolution, Flaxman was a pioneer in the art of reproduction techniques using novel methods such as plaster. So significant was the plaster revolution that when his Italian contemporary and friend the renowned Anthony Canova himself turned to plaster, it is said to have marked the end of the reign of terracotta in Italian sculpture.

Reproduction techniques preoccupied Allington. They were central in his own meditations on authenticity, origins and truth that recur in his own writings [4]. A frequent visitor to the museum and occasional collaborator, Allington undertook another site-specific exploration with the small bronzes. Together with a photographer, this time with Heini Schneebeli, he placed the small bronzes in UCL’s museums, including amidst skeletal reproductions in UCLs Grant Museum of Zoology, and amidst various artefacts in the UCL Petrie museum of Egyptian Archaeology. The image featured here reflects his purposeful placing of Euridke. In this work – the photograph that was later exhibited with the bronze sculpture, Allington was creating a conversation about sculpture and the art of reproduction and that which is lost. To the right of Euridike is a terracotta bust of George Grote, one of the key founders of UCL and a renowned Greek scholar. Grote also donated a significant collection that followed the principles of 17th century collecting where copies of works of significance carried value as collectables in their own right. These works were then used by art students at the Slade for the purpose of copying, itself instrumental to the process of learning. In terracotta sculpture the clay model is fired up and becomes the final work. When clay is used as the basis for a plaster cast the clay model is destroyed while the cast itself allows for endless reproductions. Above and behind Euridike are examples of Flaxman’s plaster models, themselves studies that would later be scaled up and translated into marble. To the left is a sculpture of Henry Crabb Robinson, another founder of UCL, friend of Flaxman and many of his contemporaries, who was instrumental in bringing Flaxman’s studio work to UCL after the artist’s death. His efforts resulted in thirty-nine of Flaxman’s models being set into the walls under UCL’s dome with the full scale model of St Michael in the centre. The sculpture of Crabb Robinson is painted plaster, the paint imitating bronze. Euridike is also painted, in a green that echoes the naturally occurring patina that forms on the surface of bronze as a result of aging and exposure to various environmental changes.

Euridike is a cast, its placing casts its surroundings into a story, a story about casting and other reproduction techniques, institutional history, art education. The resulting work ultimately challenges our ideas and beliefs about origins.

For the exhibition Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture we chose place Euridike in a similar positioning but as we were not reproducing Allington and Schneebeli’s casting, merely referencing it, we chose a different painted plaster sculpture from our collection, a copy of Hermes of Olympia. We think Allington would have approved seeing as the origins and attribution of the original sculpture are widely disputed and copies abound. The photograph is not a work of art but a documentation of our exhibition installation, photographed by Mary Hinkley, and is purposely distinct in format from Allington and Schneebeli’s work.

Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture is part of UCL’s Year of Sculpture and continues till the 7th June, Tues-Fri 1-5pm. It is reviewed in Apollo Magazine here.

[1] Edward Allington Pictured Bronzes, with essays by Shin Ichi Nakasawa and James Roberts, Kohji Ogura Gallery Nagoya Japan in co-operation with the Lisson Gallery London, 1991, appendix p.V.

[2] Pictured Bronzes, appendix p.V.

[3] Edward Allington: A Sculptor at Work, edited and directed by Peter Colman for the Henry Moore Centre for Study of Sculpture by Leeds University Television in 1993.

[4] See for example, Edward Allington, ‘Venus a Go Go, To Go’ in Sculpture and its Reproductions, eds. Anthony Hughes and Erich Ranfft, London: Reaktion Books, 1997, pp.152-167.

Close

Close