Specimen of the Week 350: The Plastic Fantastics

By Tannis Davidson, on 6 July 2018

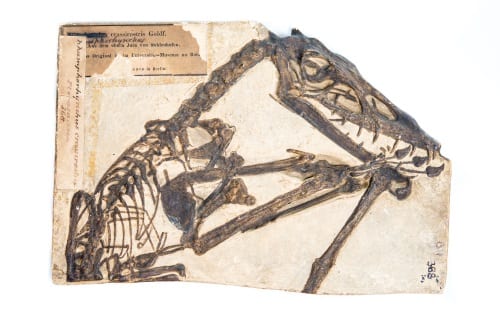

Four moulds of Australosomus merlei: Clockwise from top left: LDUCZ-V1685, LDUCZ-V1696, LDUCZ-1697, LDUCZ-V1698

This week’s Specimen of the Week is a celebration of diversity, fashion and fabulousness. It pays tribute to all the specimens who have suffered discrimination or denied equal status for not being considered ‘real’ specimens. Yes, I’m referring to the casts and particularly the moulds in natural history collections which are too seldom given pride of place on museum display shelves despite contributing an incalculable value in the transmission of scientific ideas and knowledge.

Casts in natural history museums are often considered second-class museum specimens; their primary function to exemplify the original specimen for comparative purposes. The moulds which produce the casts are arguably even lower down the ladder of regard – transitional objects used in the creation of offspring specimens (casts) and rarely displayed or considered accessionable objects in their own right.

Apart from their value as conduits of reproduction, moulds are also a resource illustrating both innovation in technique and the fashions of their time. Without further ado, this week’s Specimen of the Week salutes…

** The Plastic Fantastics**

There are many different types of casts found in natural history collections. The most common are plaster casts – created by pouring liquid plaster into a mould made from the original specimen. Once dried, the plaster cast is removed from the mould and often painted to highlight features of the specimen (as in the case of a fossil in matrix). Plaster is a traditional casting material and has been used for hundreds of years due to its affordability, ease of use and durability.

Resin is another popular material used for making natural history casts as it can be coloured and can capture more detail than plaster:

But before a cast can be produced, a mould must be made. This is the initial, critical step in cast creation whereby the information and detail of the original is reproduced as completely as possible without damaging the specimen in the process. After cleaning, a thin layer of consolidant will often be applied to the specimen to help maintain it and allow for the mould to be safely removed from the specimen. Then the moulding material (usually silicone, polyurethane rubber or latex) is poured or spread over the specimen. A detailed procedure for making moulds by Marilyn Fox, Preparator at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University can be found here.

The development of silicones and polyurethane rubbers for practical uses began in earnest through the the 1930’s and 1940’s. IG Farben in Leverkusen, Germany, first made polyurethanes in 1937 and by 1943, Dow Corning was established as a manufacturer of products for the US miliary with a focus towards investigating uses for silicone [1].

In the decades that followed, various plastics and rubbers were used for moulding and casting of museum specimens. As recorded in the Grant Museum’s Fossil Vertebrate Catalogue register, there is a wide variety of mould materials listed including brown Welvic, North Hill Plastic, red vinagel, latex and silicone-rubber :

Brown Welvic (commercial PVC Welvic) was a product made by Imperial Chemical Industries (polyvinyl chloride in Tritolyl phosphate) and in use by 1945. Current state: robust and flexible.

North Hill Plastics (London) were in business 1951-1974. The Grant Museum has several NHP casts of different colour – all are rock hard with a glassy, shiny finish. The detail in the image above shows a dark purple interior colour and also chipped, damaged edges.

Vinagel squeeze (registered trademark US, 1973) made by Vinatex Limited, Hampshire described as mouldable synthetic resin plastic for use in manufactures and plastic substances for modelling. It is solid with a little flex.

Latex is a type a rubber featuring plastic-like qualities and in its natural form is extracted from trees. These two synthetic latex moulds include white inclusions (plaster which has filled the mould holes following casting). These are more flexible than the red Vinagel squeeze mould but the brown latex has become brittle on the edges.

The details in the above silicone rubber mould have been made more visible with the addition of colour to the surface. Most of the Grant Museum silicone rubber moulds have this colouration – it lends itself to photography, but several are plain white:

The Grant Museum is fortunate to have material and company-specific details about most of its fossil vertebrate mould specimens. It has been possible to loosely date many of these moulds with the benefit of a solid date range for the production of specific materials. This can be narrowed down further by cross-checking with registers and other documentation and could inform our understanding of when these moulds were made and possibly who made them. Plastic is fantastic.

Tannis Davidson is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

References

[1] Bayer, Otto. 1947. “Das Di-Isocyanat-Polyadditionsverfahren (Polyurethane)”. Angewandte Chemie. 59 (9): 257–72.

Close

Close