Bentham the feminist?

By Nick J Booth, on 3 March 2016

Recently I was helping an artist, Kristina Clackson Bonnington, with some research into the collections I look after. Kristina is working on an event for this year’s International Women’s Day, and is starting to plan for the centenary of women getting the vote in the UK (2018). While discussing her project I thought it would be interesting to see what Jeremy Bentham’s thoughts on women’s rights were. I’m very pleased to say that he had some modern sounding ideas…

As with all my questions relating to Bentham’s life and works my first port of call was the friendly people at the Bentham Project. Their initiative ‘Transcribe Bentham’ is working to publish all of Bentham’s manuscripts and is finding now information all the time. One recent manuscript they sent me is pictured below, and rather wonderfully shows Bentham arguing for the use of gender neutral pronouns.

When both sexes are meant to be intended, employ

not the word man– but the word person

26 When both sexes intended employ person not man

Let it be understood that when the word person is

thus employed he the pronoun masculine includes the female

sex as well as the male

See here for the Transcribe Bentham manuscript page.

Tim Causer, of the Bentham project, also sent me a very interesting article by Miriam Willford, Bentham on the rights of women, who makes it clear that she believes that Bentham was a feminist. She argues that “His attitude toward women was actually another natural application of his own greatest happiness principle. Again and again in discussing various topics from suffrage to the Spanish Constitution, Bentham comments that he could see no reason why the female sex had less claim to happiness than the male; indeed, perhaps women’s claims to happiness was better than man’s.” She goes onto list a number of works in which Bentham shows his feminist credentials, including Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1780) and in the introduction to his Plan of Parliamentary Reform (1817).

However sadly in the first volume of Constitutional Code (1827) Bentham seems to accept that although universal suffrage is preferable, it wasn’t possible at that time as too many people were against it. Miriam Willford quotes Bentham – “Why exclude the whole female sex from all participation in the constitutive power? Because the prepossession against their admission is at present too general, and too intense, to afford any chance in favour of a proposal for their admission”.

Bentham also argues that while he believes marriage for life is the most ‘natural’ state of things, being trapped in a loveless or abusive marriage is dreadful and women should have the right to divorce (or dissolve a marriage as it was called then) if they wish – “To live under the constant authority of a man that one detests, is already a species of slavery: to be constrained to receive his embrace, is a misery too great to be tolerated even in slavery itself”. I have been reading about Lady Byron recently and when she was seeking a separation from Lord Byron (in 1816) a legal separation could only be initiated by a women if the man was guilty of adultery and / or physical abuse, and even then her claim would be rejected if she showed by act or deed that she had forgiven the husband – evidence of forgiveness could apparently include staying in the house after learning of adultery, meeting him after leaving home or writing ‘in a loving way’.

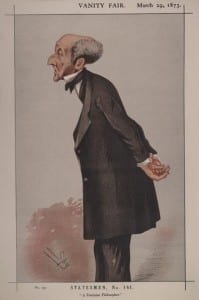

“A Feminine Philosopher”. John Stuart Mill caricature by Spy published in Vanity Fair in 1873.

Image from Wikipedia.

However, arguably Bentham’s biggest contribution to women’s rights in Britain is the influence he had on his protégé – John Stuart Mill. Mill had been educated by his father, James Mill, with advice from Bentham – which apparently included learning ancient Greek from the age of three and Latin from eight. His education is interesting (and a little sad) in itself and I don’t have time to go into it here (though this website has a nice overview). It’s enough to say that JS Mill was raised in the ‘best’ utilitarian principles and while he would go onto to believe that Bentham’s Utilitarian ideas were too limited, they had a profound effect on his character, life and works.

John Stuart Mill and his wife Harriet Taylor Mill wrote a number of influential works on women’s rights including The Principles of Political Economy (1848), The Enfranchisement of Women (1851) (published in Mills name but written by Harriet), On Liberty (1859) and (with Harriet’s daughter Helen) The subjection of women (1869). From 1865 – 1868 John Stuart Mill would serve as an MP and would be the first to call for women to be given the vote, introducing a bill on this subject written by Richard Pankhurst (Emmeline Pankhurst’s husband). His ideas and arguments would influence many arguing for women’s suffrage in the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

UCL will be celebrating International Women’s day with a series of events throughout March . More information on Kristina’s exhibition can be found here.

Much of my information for this blog comes from the article ‘Bentham on the rights of women’, By Miriam Willford, published in the Journal of the history of ideas, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jan – March, 1975), published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Nick Booth is one of the Teaching and Research Curators at UCL.

Close

Close