Specimen of the Week: Week 157 (an exciting rediscovery?)

By Mark Carnall, on 13 October 2014

Segueing nicely on from Jack’s evolution of life on land specimens of the week last week, we’re sticking to specimens in our ‘MEET THE ANCESTORS’ case. This week’s specimen is a rather lovely fossil and whilst undertaking a bit of research for this blog post I uncovered a rather twisty turny series of clues that point to this specimen being a ‘type specimen‘.

Segueing nicely on from Jack’s evolution of life on land specimens of the week last week, we’re sticking to specimens in our ‘MEET THE ANCESTORS’ case. This week’s specimen is a rather lovely fossil and whilst undertaking a bit of research for this blog post I uncovered a rather twisty turny series of clues that point to this specimen being a ‘type specimen‘.

Type specimens are important specimens in biological classification that are the specimens which exemplify the characteristics of a new species of organism. In theory, together these specimens are the physical representations of the current understanding of the diversity of life on earth and accordingly are very important specimens in museums. It’s not 100% clear if this fossil is the type specimen hence all the cautious maybes, possibles and potentiallys but you can judge that for yourselves below. So with no further ado, this week’s specimen of the week is…

** The possible type specimen of Lystrosaurus curvatus**

LDUCZ-X1053 Lystrosaurus curvatus fossil skull and partial pectoral girdle. The large orbit and the tusk like teeth can be seen on the left in this image.

1) Is it a dinosaur? You may be suprised to find out that not every organism with a ‘saurus’ in it’s name is necessarily a dinosaur, smart alecks amongst you of course will refer to the thesaurus as one example. Etymologically, ‘saurus’ is a latinised version of the Greek word ‘sauros’ meaning lizard, so we find it in the names of many different kinds of reptiles from dinosaurs, to crocodiles, to lizards and even mythological reptiles such as Cadborosaurus. Lystrosaurus curvatus is a species of dicynodont therapsids, a group of tusked animals commonly (and slightly misleadingly) referred to as mammal-like reptiles. More correctly they are reptiles in the group that evolved into and includes mammals. So that’s clear as mud. Alternatively, Lystrosaurus is related to Moschops if you remember the 1980’s stop-motion children’s series.

Reconstruction of Lystrosaurus murrayi. Image by Dmitry Bogdanov CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

2) Reptile Pig, Reptile Pig. In life, Lystrosaurus is thought to have been a pig sized animal with only two large tusks and possibly a beak. They were robust herbivorous animals and one of the most common terrestrial vertebrates of the Permian and Triassic Periods some 250-240 million years ago. Lystrosaurus fossils, have been found, sometimes in abundance, in Antrartica, South Africa and India. They are notable as one of the few terrestrial animals that survived the Permian-Triassic extinction event (the big one). Why this may be the case when millions of animals, including many groups of animals which had existed for millions of years before is one area of scientific speculation with theories ranging from Lystrosaurus being adaptable to climate change, escaping to aquatic refugia and even the very scientific proposition that they were just lucky.

3) Discovery and Description. Lystrosaurus was first described in 1870 by American palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope, of ‘bone wars‘ fame. In the middle of the 20th Century a number of species were subsequently described from remains found in South Africa with up to 23 species recognised at one point. Re-evaluation in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s has culled that down to just four species today including Lystrosaurus curvatus, which this specimen has been identified as.

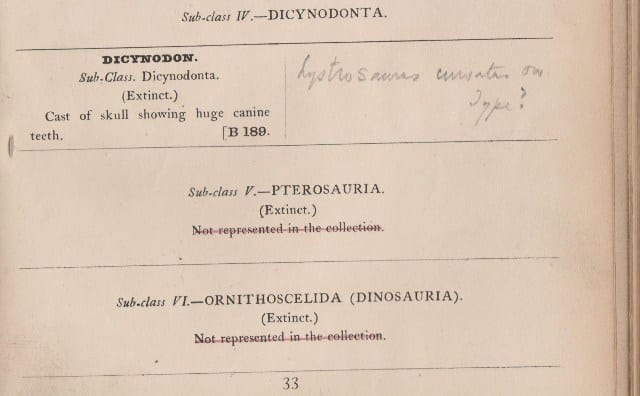

Scan of the relevant page from the 1890 Label Catalogue of the Zoological Collection with the cryptic note.

4) Missing type specimen? Whilst researching this specimen for the blog I came across an added entry in our 1890 catalogue of the collection here alongside an entry for a Dicynodon skull which cryptically says “Lystrosaurus curvatus ow. Type?”. Although published in 1890 this particular catalogue was added to at least through to the 1920s and possibly after. It is unclear who added the entry but the ‘ow’ bit in the added notes refers to Richard Owen who coined the species Lystrosaurus curvatus (under the name Dicynodon curvatus) in the volume Descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the collection of the British museum. In this volume Owen described the species with reference to a, sadly not illustrated, cast taken from a specimen from South Africa which was loaned to him by a Professor John Morris F.G.S of University College London, which is where the Grant Museum and specimen is today! Could this be the specimen that was loaned to Richard Owen and is the name bearing type for Lystrosaurus curvatus? In which case it’s an important specimen with an important historical association as well as being the golden example of this species.

5) Not a missing type specimen? If that wasn’t tentative enough, there are a number of spanners in the works that contradict this version of events. In later papers, the type specimen is given as a specimen from the same locality as Professor Morris’s specimen numbered BMNH R3792, a Natural History Museum number even though Owen didn’t use this number in his original description (King and Jenkins 1997). Owen describes the specimen as “the cast of a skull wanting a jaw”. Our specimen sort of has a jaw. The rest of the description is fairly vague and could and couldn’t refer to the specimen above. Furthermore, our specimen here is numbered with an ‘R’ number but it’s R[?]829 and there’s another number that has been purposefully scratched off. Further confusing matters, it’s also labelled C.U.M.Z. suggesting it had a spell at Cambridge University Museum. Unfortunately, I’ve not managed to find and of these numbers in subsequent papers or on the online catalogues of the Natural History Museum, Sedgwick Museum or Cambridge University Museum of Zoology. So this may be just another specimen of Lystrosaurus.

I’ll be following up this story with all the museums involved and I’ll post any updates here but it’s all part of the detective work that can make working in a museum so much fun.

UPDATE: 17/10/2014 Following a call to Twitter for help from Lystrosaurus aficionados, Christian Kammerer (@Synapsida), postgraduate researcher at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin got in touch with a photo of the Lystrosaurus curvatus type specimen now at the Natural History Museum London. According to the label for the specimen, the type specimen was exchanged with UCL in June 1910, possibly explaining the entry in our catalogue that started this investigation. The label on the NHM specimen also mentions that the type was figured in Owen’s 1876 paper (it’s described but not figured as far as I can work out). Christian also redetermined our specimen as “Lystrosaurus murrayi. Judging by the color of the bone and its matrix I’d guess it’s from Harrismith, an extremely productive Lystrosaurus Zone locality in the Free State. A number of Harrismith lystrosaurs collected by R. Putterrill eventually made their way to London”. Thanks again to Christian for providing the information whilst on the road and I’ll be in touch with the NHM to try to find out what we exchanged this specimen for back in 1910.

References

King, G.M., and Jenkins, I., 1997, The dicynodont Lystrosaurus from the Upper Permian of Zambia: evolutionary and stratigraphical implications: Palaeontology. v.40. 149-156.

Owen, R. 1876. Descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the collection of the British museum. British Museum (Natural History), London, 88pp.

Mark Carnall is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

3 Responses to “Specimen of the Week: Week 157 (an exciting rediscovery?)”

- 1

-

3

Around the Archaeology Blog-o-sphere Digest #7 | Doug's Archaeology wrote on 19 October 2014:

[…] […]

Close

Close

An intriguing story! I’ve heard that one of the UCL Professors (name withheld) was caught stealing BM(NH) specimens so that could explain the scratched off numbers. Our Mammal-like reptile collections are somewhat at the back of the queue for databasing, so perhaps not all are in the online database yet. You need to contact Sandra Chapman at NHMUK, who curates the mammal-like reptiles. She can probably help but would also be interested to hear what you’ve found out so far!