Specimen of the Week: Week 155

By Tannis Davidson, on 29 September 2014

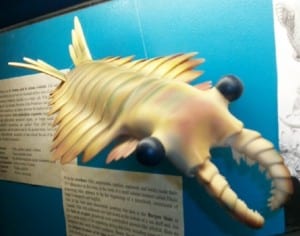

Hello all. In anticipation of writing my first Specimen of the Week post, I wondered which specimen would ultimately receive the honour. I wanted to highlight a specimen representative of my Canadian homeland such as a fossil from the Burgess Shale, but the curator (see SOTW 140) beat me to it. Sadly, the Grant Museum has but one documented specimen from this phenomenally important fossil location. The Burgess Shale has famously yielded dozens of previously unknown 505 million year old fossil organisms such as the evocatively named Hallucingenia, five eyed Opaginia, and the fearsome-looking predator Anomalocaris.

Hello all. In anticipation of writing my first Specimen of the Week post, I wondered which specimen would ultimately receive the honour. I wanted to highlight a specimen representative of my Canadian homeland such as a fossil from the Burgess Shale, but the curator (see SOTW 140) beat me to it. Sadly, the Grant Museum has but one documented specimen from this phenomenally important fossil location. The Burgess Shale has famously yielded dozens of previously unknown 505 million year old fossil organisms such as the evocatively named Hallucingenia, five eyed Opaginia, and the fearsome-looking predator Anomalocaris.

As it turns out, I was able to find an interesting animal from the collection…one which might possibly be a living relative of Anomalocaris!

This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

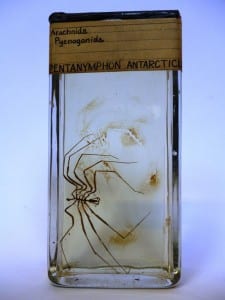

**The Sea-Spider: Pentanymphon antarcticum**

1). What is it?

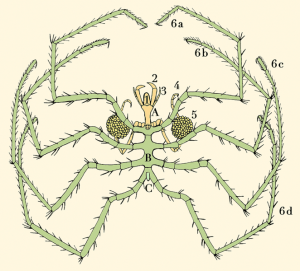

Pentanymphon antarcticum is a ‘sea spider’ belonging to the family Nyphomidae in the class Pycnogonida which comprises over 1000 named species. The pycnogonids are marine arthropods and although not true spiders, their classification places them closer to arachnids than other arthropods such as crustaceans and insects. Sea spiders have long, spindly legs and a small body with between four and six pairs of walking legs (Pentanymphon antarcticum has 5 pairs).

Due to their small size (the length of the body of the specimen pictured above is 1.2 cm), no respiratory system is necessary and each of their tiny muscles consists of only one single cell surrounded by connective tissue. The bodies of pycnogonids include a proboscis which can be used for feeding by sucking nutrients from soft-bodied invertebrates such as sponges and sea anemones. Such species have palps (which also function as mouth parts) and ovigers which are used for cleaning, courtship and carrying the young.

2). Daddy larval legs

After a brusque courtship, reproduction occurs after external fertilisation. Embryos and the young (when hatched) are carried and cared for exclusively by the males (on their legs). The larvae maintains its embrionic form – just a head with its appendages. The thorax, abdomen and legs grow later.

Anatomy of a pycnogonid: A: head; B: thorax; C: abdomen 1: proboscis; 2: chelifores; 3: palps; 4: ovigers; 5: egg sacs; 6a–6d: four pairs of legs /

Sars, G. O. (1895). An account of the Crustacea of Norway, with short descriptions and figures of all the species. Christiania, Copenhagen, A. Cammermeyer.

L. Fdez (LP) – digitization and colouration. (CC BY-SA 2.1 ES)

3). But what about Anomalocaris?

You may have noticed the chelifores above (numbered 2 in diagram). These are a pair of fang-like structures at the front of the head. Research by Maxmen, Browne, Martindle and Giribet (2005) suggests that pycnogonid chelifores may be homologous to the great appendages unique to certain groups of extinct arthropods such as Anomalocaris. What this means is that the chelifores in pycnogonids such as Pentanymphon antarcticum developed from the protocerebrum (the anterior part of the anthropod brain). In all other living arthropods, this first head segment contains the eyes only. This anatomical peculiarity can only be seen in, you guessed it, the extinct family Anomalocaridae. This may suggest that the Pycnogonida are a sister group to all living arthropods and are therfore the last surviving members of an ancient stem group which included the Cambrian Anomalocaris.

Anomalocaris Model, National Dinosaur Museum, Canberra, Australia. Image obtained from http://commons.wikimedia.org taken by Photnart

4). Chill, Bill.

If you are interested in seeing this living ‘living fossil’, prepare yourself for a journey waaay down south. As its name indicates, Pentanymphon antarcticum is only found in the Southern Ocean off the coast of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. However, as I mentioned above, there are over 1000 different species of sea spiders and most are generally found in warmer waters such as in the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas.

References

Maxmen, A., W.E. Browne, M.Q. Martindle, G. Giribet (2005). Neuroanatomy of sea spiders implies an appendicular origin of the protocerebral segment. “Nature”, 437: 1144-1148

Tannis Davidson is Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week: Week 155”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] […]