Curating, collections and two postcard albums

By Mark Carnall, on 25 April 2014

Guest post by Stefanie van Gemert (Dutch and Comparative Literature) one of the curators of the current Octagon Gallery exhibition, Collecting: Knowledge in Motion.

In this time of new media, we are all curators. We pin our interests on digital gallery walls and make collages out of faces on ‘the Book’. Tweeting and status-updating, we display our collections of Instagrams. I find this idea of self-styling through collecting fascinating. And this is only one of the many reasons why I thoroughly enjoyed working as co-curator on the current Octagon Exhibition Collecting – Knowledge in Motion (#uclkimotion) with Prof Margot Finn and Dr Kate Smith (History), Dr Claire Dwyer (Geography) and Dr Ulrich Tiedau (Dutch department).

What Moves Collections

Our curatorial team applied for a bid called ‘Movement’ in Spring 2013. We were invited to explore the many collections at UCL and to display our findings in the new Octagon space. The Octagon Exhibitions are meant to show interdisciplinary research at UCL. As Claire explained in her previous blog: our bid spoke of our mutual interests in material cultures, in colonial heritage and global migration. But when we saw UCL’s vast collections, our ideas took a different direction. What is on display in the UCL Museums is only the shiny tip of a glorious iceberg of objects, stored in the basements of our campus. We felt spoilt for choice, quickly becoming enchanted by stories of movement related to the objects and collections at UCL.

We wondered what it is that makes a collection. Is it the value of the collection’s objects itself? Or do the narratives about objects make them valuable? Or does it perhaps start with the collector: is it his determined self-styling, her personal story that draws the collection together? These questions both address the collection as a complex and mobile entity and the idea of curatorial practice itself – what drives individuals to make a display or to start collecting?

Without becoming too philosophical about what was often a good bit of fun, I will discuss two objects from Knowledge in Motion you can now see in the Octagon Gallery. They sit in a case that explores this 1657 Rembrandt print from the UCL Art Museum, portraying the collector, Abraham Francen. The case mirrors the 17th-century collection of Francen and, thus highlights ideas about networks of objects, artists, collectors and curators related to UCL’s collections, across time.

The two objects are actually collections themselves, collected by artists who studied and worked at UCL’s Slade School: Stanley and Gilbert Spencer and Bartolomeu dos Santos. Both collections focus on a medium that enables movement of images and text: the postcard.

Dos Santos’ networked Christmas Cards

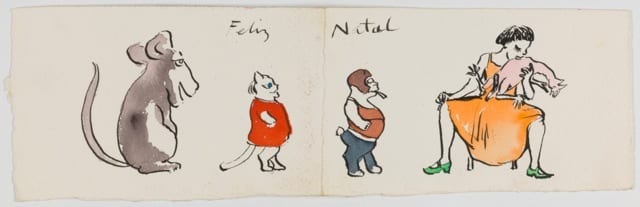

Like Rembrandt, Bartolomeu dos Santos was fond of etchings and prints. He was Professor in Print Making at the Slade from 1961 till 1996. His Christmas Card collection shows what an extremely charismatic figure ‘Barto’ must have been. His students stayed in touch with him for years, sending him their handmade cards. I loved Barto’s mixed collage cards.

The medium of print was developed to reproduce images, creating many copies of one original. But Barto and his students would individualise their cards: adding little notes to their prints, colouring them by hand and glueing ribbon or Christmas tree branches on them. These cards reflect individual friendships. As such they are part of a trail, showing Dos Santo’s network of printmakers. The evident affection between Barto and his students makes this collection a joy to research. The bizarre animals of Dame Paula Rego at such a small scale; the inside jokes about teddy bears: it is all far away from the dime a dozen Christmas cards with red-nosed reindeers from Tesco’s.

The Spencers’ album: imaging postcards

The postcard album of the two brothers Stanley and Gilbert Spencer show relations between artists across time and place too. The cards were sent to the Spencers by friends and fellow-students at the Slade. They reveal how the brothers educated themselves through reproductions of artworks. But the reproductions proved not to be the ‘real thing’.

When Gwen Raverat – another Slade-trained printmaker – travels to Florence in 1914, for example, she tries to explain the beautiful colours in Italy to the Spencers. But because of the black-and-white reproductions, she has to make up for lack of colour in words:

‘We’ve been today to see some painting by Andrea Castagno […] There’s a great last supper, but it has been sadly repainted + all the colour dirtied. I’m sending one to Gil but you can’t see much in it’

Or she needs to think of similar paintings in London, that the brothers perhaps know:

‘the hills near Florence are incredibly beautiful: the colours are all so light & dry & fine: it is like the ‘Nativity’ by Piera della Franscesca in the Nat. Gal. or a little bit like the Boticelli’ Spring even!’

And sometimes Raverat simply cannot find the right postcard:

‘This [painting by Castagno] is not the one I liked best but there were no other photographs’.

The Spencers’ postcard album questions what is lost when we see the Mona Lisa in print instead of live in the Louvre. What happens if we resize a painting to postcard dimensions, or print a statue in 2D? It looks like the Spencer were perfectly happy to make up for the ‘gaps’ in their collection with their imagination. Stanley who was famously devoted to his home village Cookham, strikes me as a curator par excellence, saying:

‘I wish the National Gallery was in Cookham, but I have many reproductions of fine pictures of old masters’.

If you would like to see the Spencers’ postcard album or Barto’s Christmas cards, Collecting: Knowledge in Motion is still on display in the Octagon Gallery until June 2014.

If you are a member of UCL staff and interested in applying for the next Octagon scheme, here is more information.

Stefanie van Gemert is a PhD Candidate in Comparative Literature at the UCL Dutch Department.

Close

Close