Pottery Project guest Blog: Pottery on the move.

By Alice Stevenson, on 15 April 2014

Guest blog by Margaret Serpico

In our fifth in the series on different perspectives on Egyptian pottery Mararet Serpico, Curator of Virtual Resources at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, looks at the topic of transporting commodities.

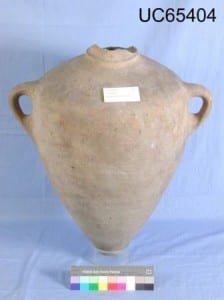

I never cease to be amazed by the lengths ancient Egyptians and their neighbours went to transport goods back and forth to each other around the Mediterranean. Especially when it involved moving small, delicate pottery containers or, alternatively, large pottery storage jars (which even empty weigh a lot!) over great distances. We are lucky in the Petrie Museum to have a number of these large jars in the collection. Not only did they make it around the Mediterranean, but they also made it here to England.

Particularly interesting to me are jars like the one above, usually called Canaanite amphorae. These were frequently used for transporting fluid or semi-fluid commodities like oils, fats, honey, resins and wine to Egypt during the New Kingdom. The neck and rim of the jar shown here is missing, most likely lopped off by an ancient Egyptian eager to remove the sealing for the jar and get to the precious contents.

Scene from the tomb of Parennefer at Amarna, showing him receiving prestige gifts. Can you spot the Canaanite amphorae? (from Davies, Rock Tombs at Amarna VI, pl. IV, reproduced courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society).

Called ‘Canaanite’ because of their presumed origin on the eastern Mediterranean Levantine coast, these jars represent a lengthy chain of contact: the potter(s) who made them; the people who filled them; the administrators who recorded shipments; the ship crew (usually they were sent by boat) who transported them; the officials who documented their arrival in Egypt, the people who delivered them to their intended destination, and the men and women who finally used the products. How many hands touched these jars before they reached us here today? How many backs ached from carrying them?

Fortunately, from inscriptions on a few of the jars, we can actually get some idea of the people involved. Petrie found a number of inscribed Canaanite amphorae when he excavated what is called the Great Palace at Amarna in 1892. Most probably daunted by the prospect of bringing lots of these large vessels back, Petrie focussed on keeping just the inscribed parts of the body of the jars.

Many relate to the transport of oils or incense. Although the inscriptions are often fragmentary or difficult to read, and slight variations occur, the formula of the inscriptions is usually “Year 2, oil (or incense) of the Per-Aten (the Great Aten Temple), delivered by the ship’s captain [name], purified(?) by the oil boiler [name] and (given to) the guard [name]”. Others mention delivery not by a ship’s captain but by a troop commander. Here, Year 2 might refer to the reign of the famous king, Tutankhamun. The darker colour of the area over the inscription was a coating put on the fragments after they came to the museum to try to preserve the writing.

The inscriptions, therefore, suggest that the jars were sent to the palace from the temple, and we know that the jars were guarded, perhaps while they were in the temple storerooms. We also have the names of some of the individuals involved. The names of the ship captains include Ta-sa-iunu, and Mery-ra. These names suggest the captains were Egyptians. We know the name of one of the oil boilers, Kha-em-waset, and of one the guards, Ipy, again Egyptian names.

Storerooms at Amarna showing imported products including Canaanite amphorae on the right (from Davies, Rock Tombs at Amarna I, 1903, pl. XXXI, reproduced courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society).

But the inscriptions tease us by answering some questions and raising others. Why was a troop commander involved, especially if the jars were shipped by maritime routes? What was the ‘purification’ carried out by the oil boiler? Did it relate to straining the oil or resin to make sure there were no plant remains or was it some quality assurance? Was it a ritual procedure? Where was this carried out? Who wrote these inscriptions? When in the transport chain were the jars inscribed? At the original port? When they arrived in Egypt? When they reached their final destination?

I’ve long been intrigued by these questions and wish I knew the answers. Perhaps fellow bloggers have some ideas!

Close

Close