Specimen of the Week: Week Ninety

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 1 July 2013

Whilst wandering around the Museum (as Museum Assistants do) this week I noticed a bizarre bone growth on a skull on display. Any such bone growth is immediately looked for on the other side of the skull because that would indicate (though not conclusively) that it was a natural phenomenon. The left hand side of this skull had no such growth. Dun dun duuuuuuuuuuuun. This is what we in the biz call a pathological specimen, i.e. something that is caused by or is involved in some way with disease. Having a weird fascination with disease, as most biologists probably do, the skull moved up on my list of which I like the most out of our 68,000 specimens. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

Whilst wandering around the Museum (as Museum Assistants do) this week I noticed a bizarre bone growth on a skull on display. Any such bone growth is immediately looked for on the other side of the skull because that would indicate (though not conclusively) that it was a natural phenomenon. The left hand side of this skull had no such growth. Dun dun duuuuuuuuuuuun. This is what we in the biz call a pathological specimen, i.e. something that is caused by or is involved in some way with disease. Having a weird fascination with disease, as most biologists probably do, the skull moved up on my list of which I like the most out of our 68,000 specimens. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

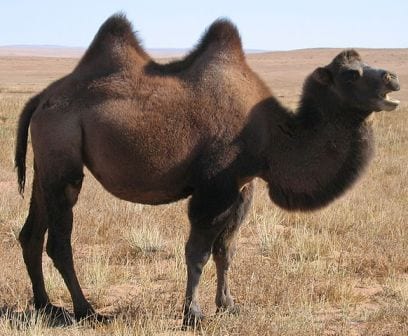

**The camel skull**

1) Camels have two toes and two ‘fingers’. They evolved in this way to ensure they fitted nicely into the group called Artiodactyla which comprises ‘even-toed hooved mammals’ such as cattle, antelope, goats, deer, pigs, giraffes, and hippos. Their closest relatives are the llama, plus the other, prettier, better-mannered, Andean llama-esque species; vicuna, alpaca and guanaco. There are two species of camel; the first has one hump; the dromedary camel that was domesticated by humans between 4000 and 6000 years ago, and second has two humps; the bactrian camel i.e. the ‘real’ camel. Our specimen is not sure which it is. And nor are we.

2) The camel skull at the Grant Museum once lived at London Zoo. It was more fleshy and animated then of course. Although, sadly, precise information was not recorded, a specimen label exists that strongly suggests that the camel almost definitely was born, died or perhaps was donated to the Museum, in January of 1964.

3) Although both species of camel are only native to Asia and Africa, the group first evolved in North America between 40 and 45 million years ago. Excitingly, if you like camels, or random science facts, this makes them some of the oldest even-toed hoofed mammals in the group (called Artiodactyla, in case you’d forgotten already). The ancestors of our camel only spread across to Asia between 2 and 3 million years ago.

4) Long, dense, make-up-advert-esque eyelashes, plus narrow nostrils and wide spreading feet are some of the obvious adaptations that camels have evolved to cope with their sandy environment. You see sand is all well and good, until you inject a dash of strong wind and then all hell breaks loose. Sand gets EVERYWHERE. They can close their nostrils tight shut. Unless they have good sand-filters on their mouths, I guess that means they are used to holding their breath for short periods when necessary? During the winter, the camel’s hair gets thicker and shaggier to protect against the minus 40 degree Celsius weather. Desert means barren, not hot.

5) A camel’s hump is full of water. Strangely-commonplace-belief, but actual TOTAL SCIENCE LIE. It is in fact, full of fat and this reservoir of goodness allows them to survive for extended periods of time without sustenance. One camel can drink up to 200 litres of water in one sitting (according to David Attenborough, and he never lies). To conserve internal water stocks when external supplies are low, camels produce dry faeces and very little urine. They also have the ultimate antiperspirant as rather than sweat, they just allow their body temperature to fluctuate. Genius. In some areas, the Bactrian camel has gone one step further and developed an extraordinary ‘skill’ of being able to drink salt-water slush. Urgh. Perhaps not surprisingly, they are the only known mammals in the world that can stomach this feat.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Museum Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close