The Giant Thorny-Headed Worm of Swine

By ucwehlc, on 20 October 2023

The Grant Museum is currently closed for refurbishment works until the new year, but we still have plenty of exciting stories to tell from the collection.

Today’s blog is by visiting researchers Dr Andrew McCarthy and Dr Jennie C. Litten-Brown from Canterbury College, UK, who have been looking into some of the parasites in our collection. This week we meet the Giant Thorny-Headed Worm of Swine, Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus (Acanthocephala: Oligacanthorhynchidae), a parasite that causes disease in both pigs and humans, that you will be able to see on display when we re-open.

The Giant Thorny-Headed Worm of Swine

Parasitism is probably the most common life strategy on Earth. Parasites are known to be important factors in maintaining ecosystem health, and the relatively new discipline of Parasite Conservation is devoted to preventing the extinction of endangered parasite species. However, several parasites cause serious disease in both humans and livestock. With increasing trends in more ethical farming methods such as Wild Farming, (often associated with rare breeds conservation), where livestock come into close contact with the natural environment, an awareness of potential pathogenic parasites is important. Specimens of one such parasite, an acanthocephalan, may be found in the Grant Museum of Zoology.

Acanthocephalans, commonly known as the “Thorny-Headed Worms” are a group of parasites typically under-represented in museum collections. Members of the group are known to cause a disease, acanthocephaliasis, in their vertebrate hosts, and some are of both veterinary and medical importance. The Grant Museum of Zoology has in its collection both fluid preserved adult worms (specimens LDUCZ-F21, F22 & F23), and Rudolf Weisker wax teaching model specimens c.1884 (LDCUZ-F26 & F84), of one of the largest acanthocephalans known to science. It goes by the rather dramatic common name of the “Giant Thorny-Headed Worm of Swine”, Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus. It may be described as a neglected parasite upon which relatively little research has been carried out. Its scientific name refers to the large, thorned proboscis (see Fig. 1), and the leech-like (“hirudo”) nature of its body (see Fig.2 ).

Fig. 1. The Parasite: Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus.

Scanning Electron Micrograph of the proboscis bearing thorns.

(© Migliore et al. (2021) )

Fig. 2. The Parasite: Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus. Entire worm from intestine of pig.

(CDC, Public Domain via Wiki Commons)

The adult parasite lives in the small intestine of wild boar, and feral and domestic pigs (see Fig. 3), where it uses its armed proboscis to burrow deep into the gut wall (see Fig. 4) causing various pathologies which include perforation of the intestine (leading to life-threatening peritonitis), intestinal obstruction and abscesses.

Fig. 3. The Pathology: Multiple Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus adults embedded into the small intestinal wall.

(© Lance Wheeler, 2018 Courtesy of Photographer: Kaitlin Hovis, Owner of Specimen: Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology)

Fig. 4. The Pathology: Proboscis of adult worm embedded in the intestinal wall of pig.

(© Migliore et al. (2021) )

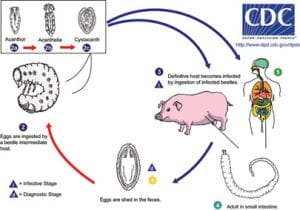

The worm has a two-host life cycle (see Fig. 5) involving an intermediate host the scarab, or dung beetle, and a definitive host the wild boar (see Fig. 6), domestic pig, or human. Infection of pigs/humans occurs by ingestion of the intermediate host as a larva or adult. Eggs laid by adult worms in the gut of the pigs pass out in the faeces and are eaten by the beetle larvae. In the intermediate host the parasite goes through three stages of development, the Acanthor, the Acanthella and finally the Cystacanth, which infects the final host.

Fig. 6. The Host in the Wild: Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) function as reservoir of infection of M. hirudinaceus.

(Image via Wiki Commons)

M. hirudinaceus is important because it causes disease in pigs, but since the 1980’s there have also been examples of infection in young children who presumably have become infected by eating beetle larvae when playing in contaminated environments. An excellent recent paper by Migliore et al. (2021) reporting on M. hirudinaceus in feral pigs in Sicily, Southern Italy, has stressed the importance of understanding this neglected parasite in domestic animals and the environment, especially as there is an increasing risk of accidental human infections. There is also some evidence in the literature to suggest that M. hirudinaceus may have a synergistic effect on Mycobacterium bovis, the cause of Bovine Tuberculosis, if an animal is infected with both.

In recent times, an increase in the amount of time domestic pigs spend free ranging as part of more ethical farming methods, (and therefore being placed at increased risk of exposure to infection), should mean that more consideration needs to be given to this parasite both in terms of its potential veterinary importance in the pig, and in its potential medical importance in the human host. Wild boar may function as a reservoir of infection in the wild and these animals have been classified by the IUCN as one of the most invasive animal species in the world today. They are omnivorous and very adaptive in terms of feeding strategies which means they could have a highly diverse parasite load in their gastrointestinal tract, including M. hirudinaceus. This could be linked to an increased public health risk in areas where wild boar share environment with domestic pigs and humans. Awareness of potential risks to livestock and human health in regions where this may occur is important, and it is suggested that the specimens of M. hirudinaceus in the Grant Museum could fulfil a very useful role in helping to educate future generations of animal scientists, conservationists, veterinarians, and medical practitioners about this zoonotic parasite.

Reference

Migliore,S., Puleio, R., Gaglio, G., Vicari, D., Seminara, S., Sicilla, E.R., Galluzzo, P., Cumbo, V., & Loria, G.R. (2021). A Neglected Parasite: Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus, First report in Feral Pigs in a Natural Park of Sicily (Southern Italy). Frontiers in Veterinary Science, Vol. 8, pp.1-6. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.659306.

Close

Close