Not all Fun and Games

By f.taylor, on 23 July 2020

This blog is written by escape room designer, museum freelancer and queer historian Sacha Coward. It explores gaming (then and now) and how playing games has always been about more than just having a good time.

Under lockdown games have become a welcome escape for so many of us. Just before typing this I was in the saccharine world of Animal Crossing sending virtual presents to a friend. Before that I was immersed in the gritty realism of The Last Of Us 2, a game which despite its exaggerated zombie apocalypse setting, can sometimes feel a little too close to home! I have been involved in online quizzes and boardgame marathons with friends over Zoom for months now. During a crisis, and particularly in times of hardship, games, as ever, are here to fill the void. But they go a bit deeper…

It’s worth saying that as an escape room designer, videogame fanatic and recently a dungeons and dragons Dungeon Master, in terms of gaming-nerdom I have got pretty good credentials! But I am also part of the LGBTQ+ community, a museum and heritage worker and I am outspoken about inclusion and diversity in arts and culture. This means I have a real fascination with games and gaming; Where they come from historically and how they are used by different people today and in the past.

Before lockdown I built a giant immersive game of Snakes and Ladders for the UCL Grant Museum of Zoology, so here I want to reflect on how and why I did it. Also I want to take a chance to briefly explore games, and look at some of the surprising things they can reveal about us. I want to think about the games we play today, the way they are evolving, and how you can see the seeds of this even in prehistory.

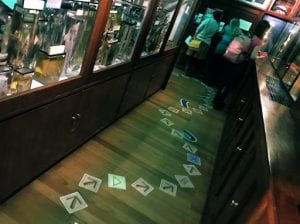

Floor vinyl created by Sheldon Goodman for ‘Snakes and Ladders’ takeover of The Grant Museum January 2020

To begin with, what is a game? It’s challenging to define exactly what a game is that includes everything that we lump under this broad category. It is more than just play (although that can be a part of it) it is a special kind of play, one that requires mutually understood rules, the presence of some kind of challenge to overcome, and an outcome or objective.

Such a description would fit equally well with Mario Kart, football, hide and seek and chess! With this definition in hand, humans have been playing games since the dawn of time. Although we don’t have physical material evidence for many games that might have been played through spoken word or action, we can still presume they were taking place. It is the ancient games with physical pieces, props and boards that we know the most about through the archeological record. The often cited oldest evidence of a game with materials associated, is the Egyptian game of Senet.

Senet dates back to at least 3100BCE. It represents the journey of a part of a person’s soul, known as their Ka, through the afterlife. it shows us something else that many games share; as well as being a fun way to pass the time, there is a central lesson or teaching goal that often applies to broader ideas of morality and society.

Even before Senet we can pretty much guarantee that games in some form or another have existed in human populations across the world since at least the dawn of modern human beings. In fact playing games is one of the defining traits that makes us human!

Today we see a myriad of games existing, played by all ages and in all areas of society. These games tell us a lot about who we are, and where we come from. A classic example is the ever fought over Monopoly; A game based on an older form known as ‘The Landlord’s Game’ created back in 1904. This game was originally designed as a teaching aid, to show and explore how economic disparity and ‘land grabbing’ was harmful and unfair. The game has since become a symbol of capitalism used by all sides of the political spectrum to explain and defend their beliefs. Most recently it was the powerful centrepiece of a speech on the impact of oppression against black people, made by Kimberley Latrice Jones during the #BlackLivesMatters protests. Games are more than games, they are some of the earliest structures we use to understand the good and bad of the world we live in.

Even one of the most seemingly simple and ubiquitous childhood games ‘snakes and ladders’ has a fascinating story that shows it too had a powerful learning objective relating to the human soul and how one should live.

Snakes and Ladders is not a Western creation, in fact its presence in the UK and Europe (and in America as the slightly neutered version ‘Chutes and Ladders’) is a direct product of empire building. ‘Moksha Pattam’ was a game which began in the Indian Subcontinent, it was part of an entire family of games arguably dating back as far as 1500BCE. These games, much like Senet, and even Monopoly, demonstrated principles relating to human life, religion and philosophy. The snakes and ladders in the game represented the conflict between Karma and Kama, I.e. destiny versus desire. Simply put, the fact that you are constrained by the random roles of a dice demonstrates the random way one might experience good and bad outcomes in life. The Victorians took this game as part of an obsession with taking, borrowing and stealing Indian aesthetics and culture. They repackaged the game with Christian values: The snakes therefore became vices, and the ladders virtues.

The fascinating colonial history of this commonplace game, and that it is a fantastic way to illustrate unfairness and bias led me to run a collaboration with the Grant Museum at UCL. On the 30th of January 2020, just before lockdown, I developed a giant immersive game of snakes and ladders as part of an evening takeover of the Museum. Working with illustrator and tour guide Sheldon Goodman and UCL museum staff I produced a giant vinyl game of snakes and ladders that had visitors walk around the cabinets as playing pieces.

We also created four different rule sets, each aligned to a different character archetype. These characters and rule sets aimed to get people to think how race, identity, sex, class and sexuality interplay in creating unfair advantages and disadvantages in real life. (This was part of the Grant Museum’s ‘Displays Of Power’ exhibition.) I felt like we were getting back to the roots of Snakes and Ladders, a tool created 3,500 years ago to teach about privilege.

Now in lockdown I am no longer building physical games, although I am creating digital escape rooms and online experiences. I am also playing a LOT of videogames; Boardgames are still alive and well but we have entered into a new world with the advent of digital gaming. Today the games we play are becoming more and more rich, complex and immersive with every iteration. Long ago this was seen as a safe space for only heterosexual cisgender male nerds, now games like every other artform are pushing for more diverse casts, and better storytelling. Mario saving Princess Peach from the castle is just not enough anymore!

Sacha runs videogame themed tours of the British Museum, where despite the lighthearted nature of the topic he covers themes of race, gender, colonisation and empire.

Even tabletop roleplaying games like Dungeons and Dragons have started to realise that despite their fantastical setting, they need to mirror the lived experience of their players. Wizards of the Coast who produce the official rule sets for D&D have made a decision to remove ‘evil’ alignment from races in their series. They argue that in today’s climate talking about entire races as inherently bad or wrong is unhelpful. This is arguably in direct response to the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Games, as ever, and just like their players, do not exist in a vacuum.

Sacha runs videogame themed tours of the British Museum, where despite the lighthearted nature of the topic he covers themes of race, gender, colonisation and empire.

There has definitely been pushback against these decisions by a vocal minority. The newly released Last Of Us 2 by Naughty Dog, features an incredibly diverse cast including a lesbian protagonist. This resulted in an orchestrated campaign of ‘review bombing’ before the game had even been released! Some gamers feel that gaming is becoming too ‘political’ that it should just be about ‘fun’. If anything, from my time building games, but even more from studying their history, I can see that games have always been hugely political. They have always had morals and were nearly always designed to teach us about real world principles.

All in all, games are this strange cool byproduct of human brains! We have been making them since the dawn of humanity, and there is something beautiful and cool to think that there is a thread that links me, killing zombies on a TV screen with a kick-ass lesbian protagonist, directly to an ancient Verdic game used to teach the Hindu and Jainist concept of karma! We play games to escape, and to let off steam, but games are created by and for real people with their own ideas, and feelings, and objectives. Next time you boot up your console, roll the dice, or shuffle a deck of cards, spare a moment to think what those sometimes hidden messages might be. But don’t worry, it’s just a game…

Close

Close