Specimen of the Week 389: The Monarch Butterfly

By Lisa Randisi, on 16 August 2019

This blog was written by UCL Culture volunteer Melissa Wooding.

Today’s specimen of the week highlights one of the world’s longest animal migrations at 6,000 miles1– completed by an insect!

This beautiful insect has an internal biology including a sundial 2 compass 3, and a gene enabling it to suppress its own ageing and increase its own lifespan 8 times4… all inside a brain the size of a single sesame seed5.

It’s time to give this mind-boggling butterfly its due moment in the spotlight:

**The Monarch Butterfly**

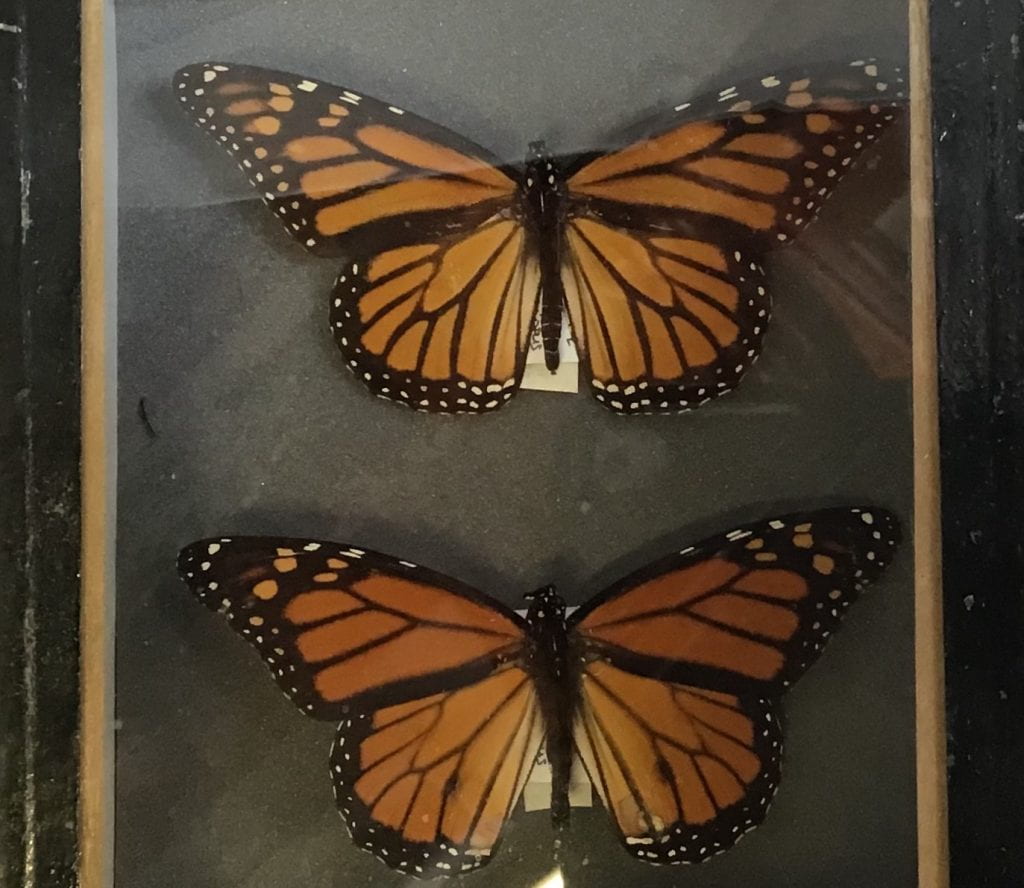

The monarch butterfly is an insect that belongs to the group of Lepidoptera, or those who have scales (lepis) on their wings (pteron)6. Like all butterflies their wings are covered in tiny scales whose shapes can create unique colours by reflecting light. The scales are also a useful defence mechanism in helping the butterfly escape from spider webs – by shedding the scales that get stuck to the web. If you’ve ever caught a butterfly as a child, the ‘dust’ that comes off in your hand are scales.7

If you look closely at our specimens in the Grant museum, you can also ‘spot’ how to tell males from females – special scales form a tiny black circle on the males’ wings.8

Monarch butterflies are particularly noted for their incredible migration over America. Monarchs that live in northern parts of America and Canada travel south every winter to escape the cold – and as anyone who has lived in North America during the winter can agree, this is a great decision. But this also means travelling over 6,000 miles there and back on a journey that will take about two months, and a single monarch butterfly will only live 2 to 6 weeks. As a result this journey takes them multiple generations. Each generation reaches its midway destination, lays eggs and dies, passing the mantle to the next one.9 Only the grandchildren of the butterflies that set out will actually arrive in Mexico, and settle in the exact same 12 mountain tops each year, filling forests and sanctuaries in Mexico and Southern California with the sounds of millions of butterfly wings.

Here is a video showing what millions of butterfly wings sound like, as well as the scale of the butterfly migration, whose final generation will still include millions of butterflies.

After their winter holiday is over and it is time to fly back in the autumn, the generation of butterflies in Mexico is triggered by shorter days, cooler temperatures and changes in milkweed plants (their main diet) to suddenly lay very special eggs10. Although the butterflies that will hatch from these are the exact same species, each one will live up to 8 months! This superpower is achieved by having a much lower level of Juvenile Hormone, the hormone that allows them to be actively reproductive but also ages them (the old sex or death dilemma). These larger, stronger and more robust butterflies have a higher stamina and will make the full journey back in one single go. They can fly 4500 km, as opposed to the normal 450 km11. Only once they have arrived will their hormone levels return to normal so that they can reproduce and then die, creating another generation of normal butterflies.

Monarch butterflies therefore have a very different life cycle depending on the place and time of year.

The secret of how they navigate is still being puzzled over by scientists, who remain amazed by the butterflies’ ability to always settle in the same specific destinations, despite the fact that, as experiments reveal, they have no internal map of their surroundings to go on12.

In short, research has revealed that they use ‘time-compensated sun compasses’. The butterflies use the sun as a giant compass to guide them southwest. They use the fact that the sun travels in a fixed path from east to west, and then combine this with a very precise internal clock in their antennae to reorient themselves in the direction they need to go, by placing themselves on its left to go south or its right to go north (using the sun alone does not work because without a clock its orientation is unclear e.g. without knowing the time, the sun on the horizon could be either dusk or dawn and therefore east or west). On cloudy days with no sun, monarch butterflies can also use their sensitivity to the magnetic fields of the Earth to find southwest13.

Research has also suggested that monarchs use wind currents, barometric pressure and surrounding geography to guide them14 – their path is flanked by the Rocky/Sierra Madre Mountains on one side and the Gulf of Mexico on the other.15 16

Using complex and mysterious navigation mechanisms and travelling huge distances precisely with no map, with 3.5 cm wings and a brain of only a million neurons is an impressive feat. As a species, humans can struggle with navigation without maps despite having brains with 100 billion neurons, and as an individual member of that species I marvel at the feats of some of nature’s tiniest travellers as I continue to search park maps for the arrow saying ‘you are here’.

—-

1 https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/10/monarch-butterfly-migration/

2 Perez, Taylor And Jandor (1997)

3 ibid

4 https://youtu.be/fBakLuH6kDY

5 ibid

6 https://www.britannica.com/animal/lepidopteran

7 https://www.thoughtco.com/touch-butterflys-wings-can-it-fly-1968176

8 https://journeynorth.org/tm/monarch/id_male_female.html

9 https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/migration/index.shtml

10 https://www.nature.com/news/monarch-butterflies-navigate-with-compass-but-no-map-1.12756

11 https://youtu.be/fBakLuH6kDY

12 https://www.nature.com/news/monarch-butterflies-navigate-with-compass-but-no-map-1.12756

13 www.repperlab.org/migration/the-sun-compass

14 Guerra, Patrick, Gegear, Robert, Reppert, Steven, A Magnetic Compass Aids Butterfly Migration, Nature Communications volume 5, Article Number 4164, 2014

15 ibid

16 “A sun compass in monarch butterflies”, Sandra M. Perez, Orley R. Taylor & Rudolf Jander, nature volume 387, page 29 (1997)

Close

Close