Specimen of the Week 381: What Lies Beneath

By Tannis Davidson, on 17 May 2019

The fluid store room for the Grant Museum is perhaps an unlikely setting for a hair-raising tale. In it, rows of metal shelves are neatly arranged holding jars of preserved zoology specimens arranged by taxonomy. Order and classification dictate the placement of specimens, and as a whole, the contents of the store are visible, documented and accessible.

Apart from the bottom shelf of the last row. Although a numbered (legitimate) location, it is a wildcard area which houses several large ceramic pots of unknown content. No one knows exactly how and when the pots came to be a part of the Grant Museum collection and because it is impossible to see into them, no one knows what they hold. A few clues exist – the occasional faded label or a more modern post-it note – but as the pots have not been opened and investigated in living memory, their contents are a mystery.

What follows is the first-hand account of the opening of two of the pots. This is a true story.

**WARNING Graphic images below **

It was the day we had been waiting for. The conservation lab was ready, the fume hood switched on and the ceramic pots in position. The conservator and I had selected two of these mysterious vessels to open with a hope-for-the-best but prepare-for-the-worst mindset. To spice it up, we had chosen one pot which hinted at its contents (‘HYRAX’ screamed the large black writing near three elegant museum labels ‘Hyrax‘, ‘Manis Tricuspis‘ and Manis Crassicaudata‘) and another pot with just the masking tape message ‘Jammed lid’. With great anticipation of decanting the promised hyrax and pangolins, the lid of ‘HYRAX’ pot was carefully removed…

What greeted the eye was immediately translated into a objectionable physical sensation deep within the abdomen. Mercifully, any associated aroma escaped up the extractor fan prior to olfactory detection. Once the eye-watering was under control, we took stock of the situation and regrouped. Armed with only nitrile gloves, some serious tongs and tweezers and (credit where it is due) a will of steel, the conservator fished out the first occupant while I tipped the pot to an agreeable angle.

What emerged was a large American possum: somehow its stiffened pose was almost serene despite the partially dissected midsection which attested to its inert condition. Why yes, there were areas of the pelt inexplicably devoid of the possum’s formerly luxuriant coat, and to be fair, internal organs are nearly always a shock when viewed outside (and still tethered to) their respective bodies but overall, possum number 1 (as it would soon be known as) was a comparatively decent-looking and entirely salvageable specimen.

We repeated this process several more times as we continued our effort to remove the contents of the pot. Each withdrawal was more difficult than the previous due to the increasingly awkward handling of the pot to produce the required geometry of access as well as the tendency of the bottom occupants to seemingly wish to remain wedged in their present abode.

It was an excruciating endeavour. Surprisingly, I gagged only once during the prolonged extraction of possum number 3. As the neck of the pot had a reduced diameter compared to the body of the vessel, a fair degree of effort was required in the manipulation of the carcass to shimmy it out like a gruesome midwifery exercise.

Once the possums were finally released, it became evident that a larger, tailless inhabitant lay in the pulpy bottom of the jar. This extraction was in some ways the most traumatising of the morning due to the advanced degree to which the specimen had been dissected and the ambition of the remaining tissue to detach from the cadaver. Carefully we tilted the heavy pot in an effort to encourage gravity to assist us in the grim task at hand. Following the deluge of sickly, tufted fluid, a courageous final effort was executed (via tongs and tweezers) and a hyrax was finally withdrawn.

A sodden label ‘Didephis sp.’ slid out with the hyrax, but no other notes appeared which may have revealed more about this dissected batch of specimens. Overall the possums were in good nick (the hyrax less so) and they will in due course be re-housed in individual glass jars, accessioned and given a new lease on life/death as specimens in the collection.

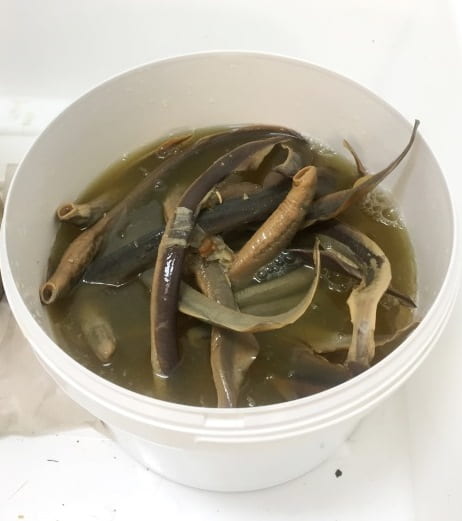

Which brings us to ‘Jammed lid’ (which I assure you it was not). In total, a remarkable 57 lampreys and one catfish were removed from this ceramic pot – whole and in excellent, robust condition. These too will be formally processed into the collection and available for future research and teaching use or possibly put on display.

And so concludes this little tale from the stores…for now. There are more ceramic pots up for investigation soon so be sure to check the blog for another (perhaps) grisly chapter.

Tannis Davidson is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week 381: What Lies Beneath”

- 1

Close

Close

Wow – that is truly hard core conservation and curatorial team work !!!