Plural Animal Wednesdays

By ucwehlc, on 24 April 2019

This blog is about a centuries-old quirk of the English language that has become a Grant Museum tradition.

If you follow us on twitter (@GrantMuseum) you may have come across Plural Animal Wednesday (#PAW), our weekly tweet about collective animal nouns. These are the words used to describe groups of animals, you are probably familiar with a herd of sheep, a flock of birds and a swarm of insects. There are, however, an astonishing number of obscure and wonderful plural animal names, enough to keep us in tweets for years and years.

#PAW was the brainchild of former Grant Museum Curatorial Assistant Emma Louise Nicholls. It all began on 16th November 2011 with a crash of rhinos (because rhinos are Emma’s favourite), and has continued every week for 7 years. All our plural animal discoveries are kept in a big spreadsheet and we are now approaching 400 entries. So why are there so many? Where do they come from? How long can we keep finding them to boost our social media content? Read on to find out.

A crash of white rhinos Ceratotherium simum by Chris Eason CC-BY 2.0

The other sort of venereal

The old name for our collective nouns is terms of venery. Venery is from the Latin word ‘venor’ to hunt, and should not be confused with venery from the word ‘venus’ meaning sexual indulgence, and the root of the term venereal disease. Be careful when Googling terms like ‘Victorian venery’, the results may not be safe for work.

Some of the earliest written examples of venery are from L’Art de venerie by William Twiti who was huntsman to Edward II in the early 1300s. As hunting was such an important part of life in the royal court, knowing the names for groups of game animals was a marker of class. These words were a coded language that let people know who was a wealthy, cultured nobleman, and who was not.

Later, when printing presses were introduced to England books on venery became very popular. The oldest example is the Book (or Boke) of St Albans which was published in 1486, and was written by Dame Juliana Berners. This probably makes Dame Juliana the first female author to be published in English.

The Book of St Albans contained information on hunting, hawking and heraldry, as well as collective nouns for people. These include gems such as a rage of maidens and a sentence of judges. Most importantly for Plural Animal Wednesday the Book contains dozens of plural animal nouns.

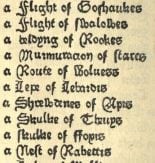

The selection above is from a Victorian reprint of a 1496 version, and includes

A Flight of Goshawks

A Building of Rooks

A Murmuration of Starlings

A Route of Wolves

A Leap of Leopards

A Shrewedness of Apes

A Skulk of Foxes

A Nest of Rabbits

Collective animal nouns are not a modern obsession, The Book of St Albans was added to, edited and reprinted many, many times right through to the 19th century. The modern version of this is, the blogs and listicles about collective nouns which pepper the internet.

A skulk of foxes Vulpes vulpes by Evas Naturfotografie CC SA 4.0

What’s in a name?

Some plural animal names are still used in everyday speech, some have fallen out of use. Some tell us about the way animals look, sound or behave, such as a bask of alligators or a murmuration of starlings. Others are sly digs at groups of people, the House of Commons can be every bit as noisy and chaotic as a parliament of rooks.

A parliament of rooks Corvus frugilegus, the one on the top left is John Bercrow. By Pauline Eccles CC-BY 2.0

In a way plural animal names make no sense for animals like leopards because they are solitary. I think we can forgive Dame Juliana her leap of leopards though, she never got to study them in their natural habitat because she was too busy being prioress of Sopwell Nunnery.

Although our plural animal names have their roots in medieval hunting, many examples are brand new. A good example is a flange of baboons, a term invented by Richard Curtis for a sketch on the television show Not the 9 O’Clock News about a talking gorilla. This term has been so popular on the internet it has started to appear on lists of plural animal nouns (including ours).

A flange of baboons Papio hamadryas by Till Niermann CC BY-SA 3.0

There is no official list of plural animal names, in a sense they are all made up. We collect ours from all corners of the internet. There are no hard and fast rules, if you like them, use them!

The science bit

The creative free-for-all of collective animal nouns is a contrast to scientific species names which are very tightly controlled. All species that have been described by scientists have a unique two part name, made up of genus and species. You are Homo sapiens, the starlings in the murmuration are Sturnus vulgaris and the baboons in the flange are Papio hamadryas.

A murmuration of starlings Sturnus vulgaris by Mostafameraji CC BY-SA 4.0

The rules for these names are set by the ICZN (International Convention on Zoological Nomenclature). The name not only identifies the species, it also shows how that species is related to the rest of life on Earth. Closely related species have the same genus name; Panthera leo is the lion, and Panthera tigris is the tiger. Related genera are grouped in families, related families are grouped in orders and so on, so that a species’ full name and classification contains a wealth of information.

This branch of science is called taxonomy and it is vital for biology as scientists need to know which species they are working on, and if it is the same species that someone else is working on. We cannot protect and preserve species if we don’t know what is out there. But like Dame Juliana before them biologists love a pun, and those puns have even crept in to the strictly controlled world of taxonomy. The valid scientific names Spongiforma squarepantsii (a fungus) and Aha ha (a wasp) are every bit as gloriously silly as a flange of baboons.

Hannah Cornish is the Curatorial and Collections Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

References

https://linguisticator.com/terms-of-venery/

https://archive.org/details/bokeofsaintalban00bernuoft/page/116

https://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2012/08/09/collective-nouns/

2 Responses to “Plural Animal Wednesdays”

- 1

-

2

Christina McGregor wrote on 6 April 2020:

Love #PAW at the Grant Museum and the realisation that anyone can author a new collective noun – or as Hannah puts it – ‘the creative free-for-all of collective animal nouns is a contrast to scientific species names which are very tightly controlled’.

Close

Close

Very interesting!