Specimen of the week 359: The Infant Elephant Molar

By Christopher J Wearden, on 21 September 2018

If you were to look inside your mouth (I hope) you would see four different types of teeth: the incisors, canines, premolars and molars. As omnivores with varied diets, humans need these different types of teeth to eat. Our molars are used for chewing, crushing and grinding the food which has been gripped, torn and sliced by the incisors, canines and premolars. Like the animal kingdom itself animal teeth are incredibly varied in their shape and size, making them a fascinating topic of study. Today’s specimen comes from an animal with fewer types of teeth than humans, but considerable size to make up for it. Without further ado let’s get our teeth into this week’s Specimen of the Week…

**The Infant Elephant Molar**

Today’s specimen comes from an Asian elephant, Elephas maximus, which is one of the three recognised species of elephant – the others being the African bush elephant Loxodonta africana and the African forest elephant Loxodonta cyclotis. The clue is in the name when it comes to guessing the range of this species as they are distributed in Southeast Asia from India and Nepal in the west to Borneo in the south. Asian elephants are highly intelligent animals. Recent studies have shown that they display mirror self-recognition, previously thought to only exist among humans, apes and dolphins [1] . This blog, however, will focus not on the intelligence of elephants but on one particularly interesting part of their anatomy.

Teething problems

Elephants have the largest teeth of any mammal. They also have a form of dentition not found in any other mammal apart from kangaroos and manatees. In most mammals – including humans – there is one initial set of teeth which is later replaced. If you think about how your own teeth develop (deciduous/milk teeth fall out, permanent/adult teeth grow in their place), this model can be applied to almost all mammals. Not elephants. As polyphyodonts their molars are replaced six times during a lifetime, and rather than grow from top to bottom their teeth are developed from the back, pushing forward in horizontal succession[2]. When a tooth wears out after years of grinding down vegetation, a new one pushes forward to replace it [3] . Think of it like a biological conveyor belt. When the final set degrades and the elephant can no longer eat, this will lead to starvation – the primary natural cause of death for elephants.

Jaw of deceased Loxodonta africana by Christopher Cooper, via Wikipedia. CC-BY-3.0

On the grind

Elephants eat a lot. They spend 75% of the day eating and can consume 150kg of plant matter per day. To put that into context, that’s around double the weight of the average British male in grass, tree bark, fruit and roots every day. Eating such large quantities requires robust molars to grind down the food and make it easier to digest. Elephants possess teeth which are perfectly adapted to this diet, with morphological differences between the different species.

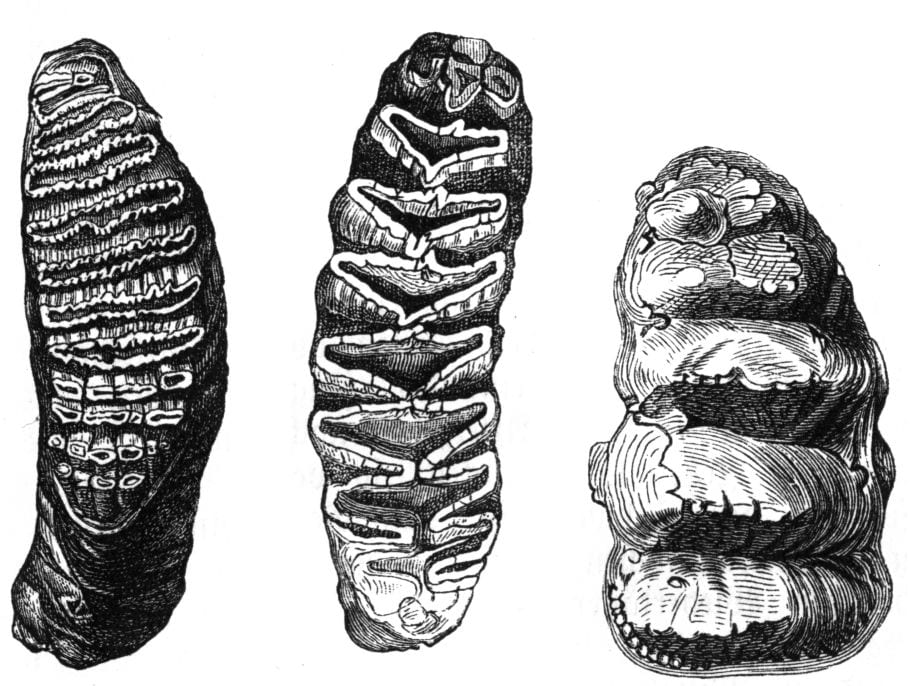

Asian elephant, African elephant and mammoth teeth sketches by Hubert Ludwig. 1891. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The illustration above by German biologist Hubert Ludwig details molars belonging to an Asian elephant, African elephant and mammoth. It accurately demonstrates some of the differences between them: Asian elephants have line-shaped ridges on their teeth whereas African elephant teeth are more diamond-shaped. Unlike most mammals who eat by moving their teeth up and down to chew, elephants move their teeth backwards and forwards (anteriorly) to grind down their food.[4]

Big babies

Elephants are fascinating not only for their teeth. They are well known for their size and baby elephants (calves) are also sizable at birth. They are born after a gestation period of 22 months, the longest of any mammal, and weigh around 250 pounds/113kg/ or 753 Guadeloupian bananas (if you were wondering). As large animals which require a lot of nutrients to grow, elephants drink up to three gallons of their mother’s milk per day and can continue nursing for the first ten years of their life. Elephants are known to develop strong bonds between friends and family members. In the first few years of their life it is likely that an elephant calf will be looked after (or ‘babysat’ if you will) by a female elephant which may not be its mother, a behaviour known as ‘cooperative breeding’. Going back to teeth, elephant calves will have their premolars and molars for the first six years of their life. Their early sets of teeth wear out much faster than those they grow later in life, which regularly last for up to ten years.[5]

Asian elephant and calf by Kalyan Varma via Wikimedia Commons. CC-BY-SA-4.0

Christopher Wearden is the Visitor Services Assistant at the Grant Museum

[1] http://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/103/45/17053.full.pdf

[2] Berkovitz, Barry, The Teeth of Mammalian Vertebrates, Academic Press 2018, p. 93.

[3] http://www.eleaid.com/elephant-information/elephant-teeth/

[4] Berkovitz, p. 95

[5] Berkovitz, p. 93

2 Responses to “Specimen of the week 359: The Infant Elephant Molar”

- 1

-

2

Varn Brooks wrote on 5 April 2021:

The tooth on the right of Ludwig’s illustration looks like a mastodon tooth? Mammoth teeth look more like the Asian elephant. I’m only familiar with the Columbia mammoth so maybe some other mammoths have teeth more like mastodons?

Close

Close

Just a note – the picture presenting elephantine’s molars has wrong description. The last to the right molar is of a mastodont (Mammut genus), not of a mammoth ( Mammuthus genus).

Best wishes! 🙂