Specimen of the Week 311: Banded Snails

By Nadine Gabriel, on 6 October 2017

Hello everyone, it’s Nadine Gabriel again. My specimen of the week is a bit of an unusual one because there are 26 of them and they’re alive! This tank of banded snails features in our new exhibition, the Museum of Ordinary Animals. Banded snails were used in 20th century genetic studies as a key model for natural selection. For the next few months, I’ll be known as the “keeper of the snails” and I would like to introduce you to these marvellous molluscs.

Say hello to our little friends

Banded snails are common garden snails with colourful and stripy shells. The two species you’ll find in your garden are white-lipped (Cepaea hortensis) and brown-lipped snails (Cepaea nemoralis). Our snails are C. hortensis because their shell lip (a thickened rim around the edge of the shell opening) is white. Both species are native to Europe and their range stretches right across the continent, from Italy to Scandinavia, and during the 20th century, they were introduced to North America. Since banded snails prefer areas with little air pollution and low soil acidification, they’re less common in London than in surrounding areas.

C. hortensis snail hungrily munching on some lettuce after arriving at the museum. They use a radula (a tongue-like organ with thousands of tiny teeth) to eat food

“They carry the genes upon their backs”

This quote from Evolution MegaLab nicely sums up why banded snails were used in early genetic studies on natural selection. Their shells are highly polymorphic which means that they show a wide range of variation; their shell morphology is determined by several alleles (gene variations). In the 1960s, scientists who studied genetics – including UCL’s Professor Steve Jones, who contributed to our Ordinary Animals exhibition – didn’t have access to the advance technology available today. By recording shell patterns and colours, scientists could understand natural selection and evolution without having to use DNA sequencing. Shells are either unbanded or possess up to five bands and the morph (colour) can be yellow, pink or brown. Shell morphology is the result of natural selection due to at least two pressures:

- Predation: Snails that are well-camouflaged are harder to catch and are therefore more likely to pass on their genes. Snails with many bands are common in grasslands and hedgerows while brown, unbanded snails are common in woodland.

- Climate: This affects shell colour. Brown shells tend to be more common in colder climates because the dark colour allows them to absorb sunlight more effectively and warm up. This means that in cold regions, brown-shelled snails tend to be more active than pale-shelled individuals.

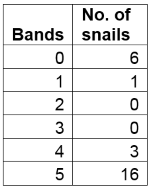

This table summarises the shell patterns of our snails. Five-banded shells are the most common, 24 are yellow morphs and only two are brown morphs. Feel free to see how many shell types you can find, some of them like to hide so you might not be able to find them all! The tank is located in the “Ordinary Animals in Science” section of the exhibition.

Citizen Science

If after reading this blog you feel like hunting after some snails of your own, check out this citizen science project by Evolution MegaLab. The researchers want to find out how shell patterns have changed over the years in response to climate, predator numbers and land use.

Nadine Gabriel is the Museum Intern at the Grant Museum of Zoology

References

http://www.evolutionmegalab.org/

http://www.animalbase.uni-goettingen.de/zooweb/servlet/AnimalBase/home/species?id=1370

http://www.molluscs.at/gastropoda/terrestrial.html?/gastropoda/terrestrial/banded_snails.html

http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/practical-biology/selection-action-%E2%80%93-banded-snails

Close

Close