Specimen of the Week 304: Fossil Box 12

By Tannis Davidson, on 11 August 2017

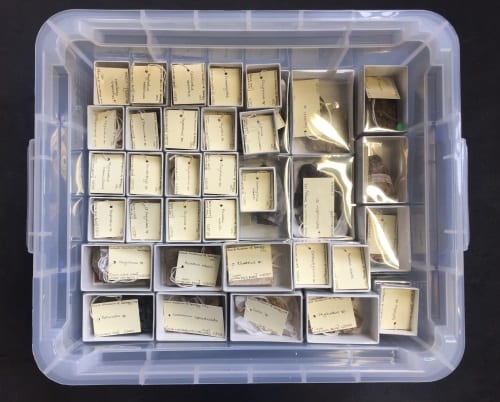

This week’s Specimen of the Week is, depending on how you count it, one single entity known as Fossil Box 12. It is also 89 individual specimens that have recently been transferred from UCL’s Geology collection. In total, 12 boxes containing 408 vertebrate fossils were transferred to the Grant Museum.

The new material is a welcome addition to the Museum’s fossil vertebrate reference collection and will be available for use in teaching and for research. Some of these specimens have already made their social media debuts such as Gideon Mantell’s Iguanodon bones and several fossil fish featuring on the Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month blog.

Fossil Box 12 was chosen as this week’s Specimen of the Week to celebrate the new fossils as well as all the work that has gone into documenting the new acquisitions.

The popular adage ” there’s no such thing as a free lunch” springs to mind whenever there is a donation offer of a specimen or specimens to the Museum. As museum folk know, acquisitions (and disposals, similarly) require work. It is not a simple process of physically handing over a specimen to a member of the museum’s staff to be immediately put on display. There are acquisitions policies and procedures to follow, due diligence checks to be undertaken to determine provenance and legality and assessments to be made (why do we want it, how could we use it, where do we put it). It is only after all the formal checks and requirements have been undertaken and signed off that a specimen can then be officially accessioned into the collection.

Which is what the Grant Museum’s Curatorial Assistant Hannah Cornish has been working on for the past 12 weeks. This involved the identification of each specimen by using old Geology inventory lists, cross-referencing spreadsheets, deciphering idiosyncratic handwriting, translating misspellings, updating taxonomies not to mention looking at each specimen itself to confirm or deny any of the above associated documentation.

Following this, each specimen was assigned a new, unique Grant Museum accession number, labelled and boxed. All information (new number, old UCL Geology numbers, entry number, paper record number, label details, markings on the specimen, date and authority of transfer, collection location and stratigraphy) was then recorded on the Museum database. This is linked to the online catalogue so all of this information can be shared with internetters worldwide.

A massive task, which I am delighted to report was completed earlier this week!

There have been many interesting finds among the new fossils including a part of a mammoth tusk found at Euston Square in 1900, the horn core of an aurochs (extinct wild ancestor of modern cows) and several woolly rhinoceros teeth. As well as material from these Pliocene – Pleistocene giants, there are new fossils from across the geologic time scale, such as fossil fish from the Devonian Period (419-358 million years ago) and pterosaur wing bones from the Jurassic Period (201-145 million years ago).

Over half of the new fossils are from fish including 18 genera which have the suffix ‘odus’ derived from Ancient Greek ὀδούς (odoús)/ὀδών (odṓn), meaning “tooth”. There is Acrodus, Deltodus, Psammodus, Gyrodus, Helodus, Ischyodus, Ptychodus, Secarodus, Coelodus, Sphyraenodus, Strophodus, Frangerodus, Otodus, Polyrhizodus, Phyllodus, Psephodus, Cochliodus, and Hybodus. The prefixes describe the shape (humped-shaped Hybobus) or characteristic of the tooth (slicing Secarodus).

The fossil remains of the “ododes” of Fossil Box 12 are unsurprisingly only teeth. These fossil teeth are from extinct sharks and chimaeras which had cartilaginous skeletons that do not generally survive in the fossil record (unlike bones). Only the hard teeth are fossilised. The exception in the above specimens is Gyrodus, a pycnodont (ray-finned fish) which is found as a full bodied fossil (just not here). However, the identification of almost 1/3 of pycnodont fish is based entirely on dental remains.

A final thought regarding the pleasure and pain of accessioning specimens (new acquisitions or otherwise): the process of documentation is exciting, richly rewarding work and not the monotonous task it may seem. The process of discovery and the actual creation of (specimen) knowledge is one of the highlights of curatorial work. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Tannis Davidson is the Curator at the Grant Museum of Zoology

References

- Delsate, Dominique and Kriwet, Jurgen. 2004. Late Triassic pycnodont fish remains (Neopterygii, Pycnodontiformes)

from the Germanic basin. Eclogae geol. Helv. 97 (2004) 183–191. [online] https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00015-004-1125-6.pdf

Close

Close