Specimen of the Week 298: The Preserved Chimpanzee Hand

By zcqsrti, on 30 June 2017

At the Grant Museum of Zoology we house enough material to comprise at least half a chimpanzee, probably even several halves…

“Half a chimpanzee, philosophically

Must, ipso facto, half not be

But half the chimpanzee has got to be

Vis-a-vis its entity, d’you see?”

I understand that by re-working Eric Idle’s Eric the Half a Bee song to read ‘chimpanzee’ instead of ‘bee’ most of the rhyming joke is lost, but I digress.

This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

~~The Preserved Chimpanzee Hand~~

Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes, along with bonobos, are our closest living relatives. They are highly intelligent, even for primates, and form societies with highly complex structures, building language, traditions and not to mention tools. But it is not the remaining post-hand specimen that I am interested in today. This solitary manus will do enough, for what lies within is extra special…

A Whistle-stop Tour of the Mammalian Wrist

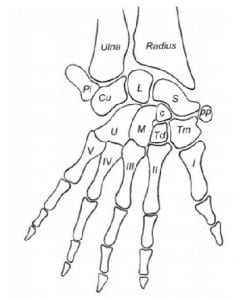

Bridging the gap between the long bones of the forearm and the proceeding bones of the digits there is a fertile land of great mystery and intrigue, otherwise recognised as the wrist. The mammalian wrist is formed of a series of globular, tessellating bones called the carpals, forming two rows. Those comprising the bottom row are the Scaphoid (S), Lunate (L), Triquetral (or Cuneiform, Cu) and Pisiform (Pi); along the top are the Trapezium (Tm), Trapezoid (Td), Capitate (C) and Hamate (H); often there are an extra two bones thrown in as a bonus: a tiny bone below the thumb called the Prepollex (pp), and an intermediary bone in the centre of the wrist called the Centrale (c).

Although relatively unstudied until recent years, the shape of carpal bones tend to provide a wealth of information relating to the ecology of the species in question, since the forearms tend to do a lot of the work an animal undertakes during its day-to-day routine. A fossorial (burrowing) animal, such as a mole, that spends most of its free time digging about in the soil tends to have a tougher and squarer set of carpal bones, thus helping resist pressures caused by the strong earthen substrate. Whereas carpals generally appear more curved and smooth in the case of species that require a large amount of dextrous movement, like gibbons and other arboreal (tree-living) primates, who tend to enjoy doing a good swingy-swingy.

The chimpanzee wrist is comprised of eight carpal bones, having lost the prepollex and centrale, the remaining majority of primates tend to have the full set of ten. Naturally the chimpanzee wrist shares a great deal of similarity with the human wrist, owing to our intimately close ancestry. Both of us have smoothed and highly grooved carpals, allowing extensive rotation and flexing, an essential condition needed for arboreal climbers. While chimpanzees do climb, they tend to be terrestrial and express a mixture of bipedal stances, often ‘knuckle-walking’ by walking on all fours with their wrists extended. Both ourselves and chimpanzees almost certainly have our complex carpal bones to thank for part of our developments in tool usage, since they allow the freedom of movement needed to carry out complex and dexterous tasks.

Canon Alberic’s Preserved Chimpanzee Hand

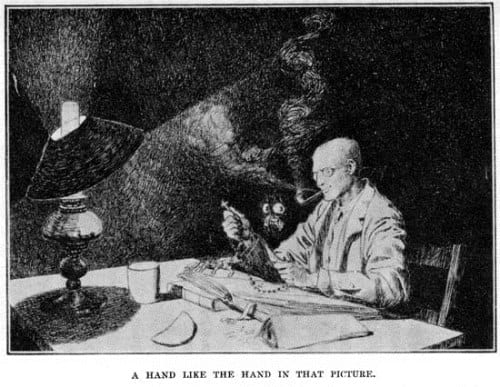

While not exactly related to the ghost stories of Montague Rhodes James, or actually belonging to the enigmatic Canon Alberic himself, this chimpanzee manus holds (at least to my eyes) a certain resemblance to the author’s first published ghost story, Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book. The story focuses on an overly curious academic, Dennistoun, who through a complicated series of events gets ahold of a haunted scrapbook. Later, while studying the book in the safety of his room, Dennistoun sleepily notices an object lying next to him upon his desk. At first mistaking it for an innocent piece of stationary, then a rat or a large spider, a dawning realisation spreads that what lies next to his own is the hand of an unseen humanoid figure:

“In another infinitesimal flash he had taken it in. Pale, dusky skin, covering nothing but bones and tendons of appalling strength; coarse black hairs, longer than ever grew on a human hand […] He flew out of his chair with deadly, inconceivable terror clutching at his heart. The shape, whose left hand rested on the table, was rising to a standing posture behind his seat.”

Illustration from Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book, unknown to Dennistoun, a hairy hand lies next to his own. Image is in public domain, author James McBride, taken from Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, M.R. James (1904).

It was this exact line that surfaced in my head as I spotted this lonely hand peering out from behind the darkened shadows of the museum. It’s human similarities briefly hint towards the uncanny; perhaps M.R. James simply drew his inspiration from the haunting elements of the natural world that are all too easy to stumble upon.

References

-James, M.R. (1904). Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. Edward Arnold & Co, London.

-Lewis, O.J. (1989). Functional Morphology of the Evolving Hand and Foot. Oxford University Press, New York.

Rowan Tinker is the Museum Intern at the Grant Museum of Zoology, UCL.

Close

Close