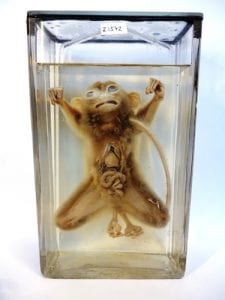

Specimen of the Week 276: The Tarsier

By zcqsrti, on 27 January 2017

In a way the shelves are an encased tomb, shut and sealed away until periodically exhumed of their contents. Eddies scatter of rime-like dust now stirred as a looming hand reaches silently into the dark. Once sleeping, now disturbed, a lingering spectre awakens and begins its reanimated shamblings anew.

We have a spirit in our midst. Not just the liquid kind either, or even a trick of the light for that matter, but a pure dead spectre in the flesh…

Tarsiers are the world’s only fully carnivorous living primate, feeding mainly on insects. There are a total of seven species, spread across the islands of Southeast Asia, but by far the coolest of which is the spectral tarsier, Tarsius tarsier. The Dayak people native to Borneo know them as Hantu, for ‘ancestral spirit’. Named aptly for its nocturnal wanderings, ghostly appearance and timid, illusive nature, the tarsier is truly a living spectre. Of the primates, this species group is a good character study of many traits and trends we observe across this rather special mammalian order…

Tarsius supposes his noses is wet, but Tarsius supposes erroneously

Primates are divided into two distinct taxonomic groups, namely the Strepsirrhini and Haplorhini, each term is, in part, derived from the Greek word ῥινός or ‘rhinos’, meaning ‘nose’. This etymological stroke of genius remarks to the differences between their noses, while strepsirrhines have a rhinarium (a specialised feature of the skin surrounding the nose that gives it a wet texture, just like a dog’s nose), haplorhines do not. Traditionally, the tarsiers would have been grouped as part of the prosimians, along with the lemurs and the lorises. However, it is now generally accepted that the tarsiers make up the earliest haplorhine group. By bridging the gap between the strepsirrhines and haplorhines, they are of a high scientific interest, and share evolutionary characteristics of both groups. For example, their small body size and grooming claws are somewhat strepsirrhine traits, while the absence of a rhinarium is quintessentially haplorhine.

Somewhat obviously disgruntled, I have tried to ask the tarsier what’s troubling it, but to no response.

‘The dreaded squish space’ and other things

The first most strikingly noticeable thing about tarsiers is their greatly enlarged eyes, which is entirely about increasing visual sensitivity in the dark. This defining character trait is due to tarsiers lacking a tapetum lucidum (literally meaning ‘bright tapestry’), a special membrane used to reflect light within the eye. A tapetum lucidum allows light entering the eye to potentially hit the retina twice, triggering a greater number of photoreceptive cells, and thereby increasing dark vision. This organ is found in many mammals, and gives that characteristic death lazer eye-shine when light from a camera or torch is shone on them at night. Lacking such a vital visual membrane at first might seem like an evolutionary shot to the foot for an entirely nocturnal living organism, but tarsiers make up for their dark vision by instead having larger eyes to intercept a greater number of photons. In fact, an individual eye is about as big as their entire brain, and is entirely immobile, instead tarsiers must turn their heads up to 180 degrees in order to look around.

The second most noticeable thing about a tarsier’s eyes is that if you were so inclined as to want to poke them, they wouldn’t get squished out of the back of their orbit. This in terms of comparative skull anatomy, is due to the complete orbit that surrounds them, unlike the orbit in strepsirrhines which does not form a complete case around the eye, and instead is made up of a post orbital bar. This bar creates a ‘squish space’ behind the orbit, which the eyeball would escape through if you were to give it a good poking.

The space created alongside the orbit by the postorbital bar in strepsirrhines, such as the galago (left hand side LDUCZ-Z398), is here depicted as the ‘dreaded squish space’. In tarsiers (right hand side LDUCZ-Z408), this is absent, and the eye is completely encased.

Snuggled up spirits

Just like the forest spirits of Princess Mononoke, the trees are a regular haunt for tarsiers, and entire social colonies sleep together within cracks of the bark. Groups venture out at night, calling to each other with high pitched peeps while hunting, and return to their nests during the day.

Body size and dietary influence

A primate’s body size can tell us, with some level of certainty, what they tend to eat. Typically, the largest primates are entirely leaf-eating (i.e. ‘folivorous’) and the smallest tend to be entirely insectivorous, while those in-between tend to be fruit-eating (i.e. ‘frugivorous’), and more open to dietary variations. Tarsiers, being one of the smallest living primates weighing in at around 100g are entirely insectivorous, but some have been known to catch small vertebrates as well, such as birds and lizards. But all of this seems a little counter intuitive. How can the largest silverback gorilla, with a body mass of up to 180Kg (that’s 1800 tarsiers mashed together, for those who are curious) sustain itself entirely on a diet of leaves, and why doesn’t it utilise a better source of nutrients, such as invertebrates, or even larger vertebrate prey? The answer, as it almost always does, figuratively lies within the bowels. A gorilla, being so large, can accommodate a much longer gut track which in turn allows for an extended digestion period of leaves and foliage, which are all very stubborn about the whole issue of digestion and are less diplomatic when it comes to relinquishing nutrients. Plus, you don’t really expect to see gorillas darting around all day expertly snapping flies out of the air with their big grabby hands; leaves are a damn sight easier to stalk and subdue (despite their best efforts and irritatingly inseparable relationship with the irksome wind).

Rowan Tinker is the Museum Intern at the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week 276: The Tarsier”

- 1

Close

Close

otis progeny