Specimen of the Week 273: The Narwhal Tusk

By Jack Ashby, on 6 January 2017

Happy New Year. It’s the start of January and we are all now staring face-first into the maw of 2017. Let’s hope it’s a good one. When the animal-owner of this week’s Specimen of the Week stares into anything, it has to do so at a distance. That’s because it has one of these giant straight tusks sticking horizontally out of the front of its face. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

~~The Narwhal Tusk~~

Dentally Different

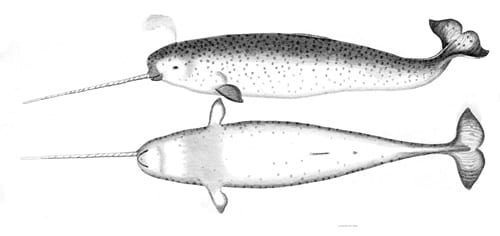

Narwhals are a kind of whale that live in the Arctic Ocean, related to belugas. They spend a lot of time around ice which is the likely reason that they have lost their dorsal fins, as they would be problematic when swimming along the underside of ice sheets. Their bodies are three or four metres long, but you may need to add another 2.6 metres to that to get their total length as the males have these extraordinary tusks. They are highly modified upper left canines which grow with a tight left-hand helical spiral. Their tusks grow straight through their upper lip, which sounds odd but I suppose means that they can shut their mouths properly despite having a giant rod sticking out of the front of it.

Twooth

It’s not particularly uncommon to find a male with two tusks (there is such a skeleton hanging from the ceiling (the traditional museum habitat of whales) of the Cambridge University Museum of Zoology). In these cases the left tusk tends to be longer, but remarkably they both have a left hand spiral – this means they are not symmetrically developed: generally body parts that grow on opposite sides of the midline are mirror images of each other. Females occasionally grow a small tusk too, but mostly it’s a male thing.

A male narwhal from “An account of the Arctic regions with a history and description of the northern whale-fishery”, by W. Scoresby. 1820

Why the Long Face?

What is the tusk for? That’s the million dollar narwhal question. Generally, when there is massive sexual dimorphism in a species (when the males and females are drastically different), the explanation has something to do with sexual selection. This is the evolutionary outcome when one of the sexes has to compete in some way for the ability to reproduce. Male deer have antlers; male antelope have horns (I wrote a blog about the distinction); male seahorses have pouches; male gorillas are giant and male peacocks have crazy tails all because of sexual selection. Therefore it’s not surprising that the most common explanation for the male narwhal’s tusk is for male-on-male fighting over females. The story goes that they would stick their tusks out in the air and use them to fence.

That would be awesome, but there are very few accounts of narwhals using their tusks aggressively.

Alternative explanations have been offered for these incredible dental spikes. Could they be for… spearing fish to eat (but then how would they get them off the end of the spear?). To ward off predators? Digging up food? As ice-anchors (walruses use their tusks to hold onto the edge of an ice floe while they sleep, among other things)? To transmit or receive sound (like other toothed whales, narwhals communicate by clicking)?

The problem with all of those suggestions is that there would need to be a good reason why tuskless females didn’t need to do the same thing.

The Tooth, The Whole Tooth and Nothing But the Tooth?

Is the answer that narwhal tusks are sensory organs? This was the conclusion of a recent study led by Martin Nweeia of Harvard School of Dental Medicine. If your teeth react to cold drinks and ice-cream, you will know that they can be sensory organs. Nweeia noted that narwhal tusks were covered in little tubules that enabled sea water to penetrate the teeth and directly contact the nerve cells in the pulp cavity of the tooth (a feature not seen in belugas, their closest relatives). They were able to demonstrate that the tusks could detect changes in salinity in the water around the tusks, giving strong evidence that they are a sensory organ. They proposed that the reason for the sexual dimorphism could be down to sexual selection: the males may use their tusks to locate females who are foraging or ready to breed by detecting their hormones or other chemical signals; or perhaps they helped find sufficient food for the calves to eat.

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

5 Responses to “Specimen of the Week 273: The Narwhal Tusk”

- 1

-

2

Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #21 | Whewell's Ghost wrote on 10 January 2017:

[…] UCL: Museums & Collections Blog: Specimen of the Week 273: The Narwhal Tusk […]

-

3

KFLatham wrote on 9 February 2017:

Is this object available for reseach and photography? I am coming to London this spring and would like to see it for a paper I am working on.

-

4

Sam Gyseman wrote on 5 February 2020:

Was this the specimen that was much vaunted in recent news articles?

-

5

Lisa Randisi wrote on 17 February 2020:

Hi Sam!

The specimen that you make allusion to is not the one from our museum.

Close

Close

Narwhal tusks used to be sold at high price – an e.g. of something that was ‘worth its weight in gold’ – by apothecaries. It was sold to the public as Unicorn Horn, valued at a medicinal cure-all and a sovereign treatment for the plague. This duplicity is confessed by Pomet in his ‘Complete History of Drugs’.