Specimen of the Week 267: The sea squirt

By Jack Ashby, on 25 November 2016

You can’t choose your family. This adage is undeniable when it comes to talking about our evolutionary history – we cannot choose to become unrelated to certain groups of animals. One of our closer relatives doesn’t look a lot like us. It is effectively a tough fluid-filled translucent bag sitting on the bottom of the sea, spending its time sucking in water and feeding on microscopic particles it finds there. This week’s specimen of the week is your cousin…

**The sea squirt**

Suck it and sea

Most members of the sea squirt’s group – the tunicates, or Tunicata – spend their adult lives permanently attached to rocks and other hard underwater surfaces processing gigantic volumes of water, sucking it in one hole (called a siphon), passing it through their gut lined with particle-filtering gills, and blowing it out another siphon. Despite looking like a wet paper bag, they actually have a brain, a heart and a kidney-like excretory system.

You’re not my mother!

Sea squirts are not your mother or your direct ancestor, but they are very much on your branch of the tree of life. In recent years molecular studies have shown that the Tunicata are actually the closest relatives to our verebrate lineage (until then they were considered the second closest relatives, after the eel-like cephalochordates). Fossils suggest that the two evolutionary trajectories began their separate journeys over 500 million years ago. While that means we are not fantastically close relatives, they are more closely related to us than bees, octopuses, worms and every other kind of animal that isn’t a vertebrate. This may be surprising because they look and behave quite a lot like sponges, the simplest of animals (which is what they were at one time considered to be).

Striking a chord

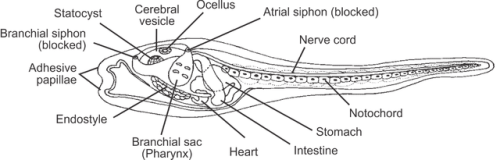

Although adult sea squirts look nothing like us or any members of the vertebrates (the first members of which were essentially fish) it has long been known that they are our close relatives, and that comes from looking at their larvae. The tadpole-like tunicate larvae have a rigid but flexible rod of tissue running down their back called a notochord. It provides an anchor for the body’s muscles and – crucially – is the precursor to the vertebrate spine. This feature is also seen in cephalochordates and together the vertebrates, tunicates and cephalochordates make up the Chordates – animals with notochords. It is the major taxonomic group to which we belong.

Above the notochord runs a dorsal nerve chord. In all other invertebrates with a central nervous system (except starfish and their relatives, which are also on our branch of the tree of life), the central nerve chord runs along the belly (a ventral nerve chord).

Baby steps

It was from looking at the embryological development of sea squirts that zoologists were able to learn about our evolutionary affinities (and after all, humans are very self-centred so any insights into the “story of us” gets disproportionate attention). Comparative embryology is a really important tool for evolutionary biologists as studying how a species’ features develop in the embryo can demonstrate that the feature in question is the equivalent structure to something in a completely different species. For example the wings of bats and fins of whales go through the same embryological processes, controlled by the same genes, because they are differently evolved versions of the same mammalian arm.

Our sea squirts

Although the “official” name for the sea squirt group is Tunicata, they are most commonly known by the name Urochordata, which was given to them by the Grant Museum’s own E. Ray Lankester in 1877. While it is very much in popular use (among biologists), it is technically illegal according to the draconian but fair laws of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature because someone came up with Tunicata first (it was the biological giant, and pre-Darwinian evolutionary forerunner, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, in 1816).

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close