The terror, the terror!

By Jenny M Wedgbury, on 15 February 2016

On 26 January UCL Art Museum hosted a Pop-Up display dedicated to the theme of the French Revolution. This ties in with our current exhibition, Revolution under a King: French Prints 1798-92. As part of our ongoing wish to support UCL students and alumni, the exhibition was curated by volunteers Viktoria Espelund, Shijia Yu and Rosa Rubner. They each chose French Revolutionary prints from our collection and approached the topic from unique perspectives. The rationale behind their selections can be seen below.

Viktoria Espelund

The assassination of Jean Paul Marat by Charlotte Corday is one of the most famous events of the French Revolution. Corday was executed by guillotine in 1793 for the assassination of Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who was in part responsible, through his role as a politician and journalist, for the more radical course the Revolution had taken. Numerous artists – most notably David, have portrayed the subject – so I decided to examine a few of these contrasting images. Whilst Revolution under a King focuses on the contemporary reaction to the Revolution, my selection not only portrays prints from the period of the assassination itself, but also material from decades after the event.

In the prints chosen, one can see a clear change in the perception of this incident. The two later works, located at the beginning of my selection, both date from the nineteenth-century. The 1823 print, for instance, is an idealised and quite sympathetic portrayal, showing Corday as a Revolutionary with ribbons of the colours of the French flag. This print however, is based on an older work from the late eighteenth-century, in which Corday is labeled as the assassin of Marat. This demonstrates that the general perception during the Second Empire (1852-1870) was largely pro-Corday; a belief reiterated by the 1863 lithograph of the assassination of Marat, in which he is seen as a revolutionary monster and Corday as a French heroine, indicated by her location in front of the map of France.

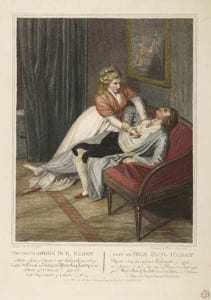

The two works contemporaneous to the Revolution generate a different sentiment altogether. The Aliprandi print (see below), published in London 1794, portrays the murder as a crime of passion. It is also apochryphal, and places the scene of Marat’s death on a chaise-lounge, as opposed to the bath tub where he was actually killed. Furthermore, the portrait of Charlotte Corday from 1793 was issued only days after her execution. Although based on an earlier print, the title line has been removed as public opinion towards her was likely in flux. The knife in her hand also looks to have been crudely addded at the last moment, thus subverting the tone of the original portrait.

Shijia Yu

Charlotte Corday’s assassination of Marat is narrated in full sequence here. Corday met her death at the guillotine, a fate shared by many others on either side of the Revolution. Arguably one of the most iconic symbols of the French Revolution, the guillotine also epitomises the controversial and complex nature of those turbulent years. The machine’s use in the beheading of Louis XVI (see lead image) marks the end of the period portrayed in the main exhibition here, as well as the Republic’s spectacular (in all sense of the word) triumph over the monarchy. However, the reaction generated by the event was far from being universally sympathetic.

As the artist of the print “Essai de la Guillotine” suggests, while the onlookers applaud for the execution of the king, the guillotine will soon turn to devour those who have brought it into use in the first place. Across the Channel, Cruikshank voices the fear for such uncontrollable terror in a much less ambiguous way. The crudely coloured yet nevertheless effectively gory depiction of the severed head and cascade of blood indicate clearly that the violence of the Revolution, represented by the guillotine, would bring much more destruction than progress. Similarly, in the print of Corday’s execution, the dignity of the supposedly counter-revolutionary (see below) stands in stark contrast against the chilling killing agent of the Revolution, posing the question again: who is the real tyrant?

Detail of Francois Marie Isidore Queverdo, Marie Anne Charlotte Corday, ci-devant Darmais Agée de 25 ans, 1795, UCL Art Museum

Rosa Rubner

The current exhibition, Revolution under a King, includes an illustration of The Women’ March on Versailles. This prompted me to consider how women from the different social strata in France were represented in popular prints during the period of the Revolution.

Within the brief period (1790-94) from which the four prints selected date, there were a number of contrasting views of events and participants depending on whether the artists were supportive or antagonistic to the revolutionary ideals, or whether they were French or English. There is, for example, a sharp contrast between the anonymous French engraver’s homely representation of the archetypal patriotic woman of the Third Estate inside her cosy home in Madame Sans Culotte and Isaac Cruickshank’s, A Republican Belle (see below), wielding a dagger and pistol in a very public space. Interestingly, each of the prints has a male counterpart: A Republican Beau and Le Bon Sans Culotte.

Continuing with the theme of the contrasting depictions of Revolution-related topics on both sides of the Channel, I have selected an engraving after a miniature of Marie Antoinette by French miniaturist P. N. Violet. The size of the original suggests that it was intended for intimate and concentrated viewing. Antoinette is depicted without any of the attributes of royalty, untainted by the ugliness of politics, in a seemingly private moment. The tone is vastly different in Frederick George Byron’s caricature. In this extremely topical work – which was published immediately after the appearance of Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France – it is the kneeling Burke, hands clasped in supplication, who is the focus of attention and ridicule. He is being mocked for his inordinate admiration of Marie Antoinette who appears here merely as an imaginary quasi-mythological figure on whom Burke’s ecstatic gaze is fixed.

For more information please go to the exhibition page for Revolution under a King: French Prints 1798-92. The exhibition is open Mon-Fri, 1pm-5pm from 10 Jan – 11 June 2016.

To find out more about our collection of French Revolutionary prints, please go to our online French Revolutionary teaching pack.

Jenny Wedgbury is the Learning and Access Officer at UCL Art Museum

Close

Close